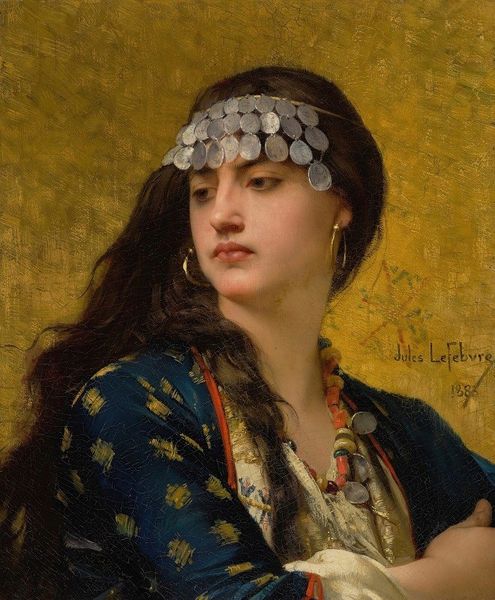

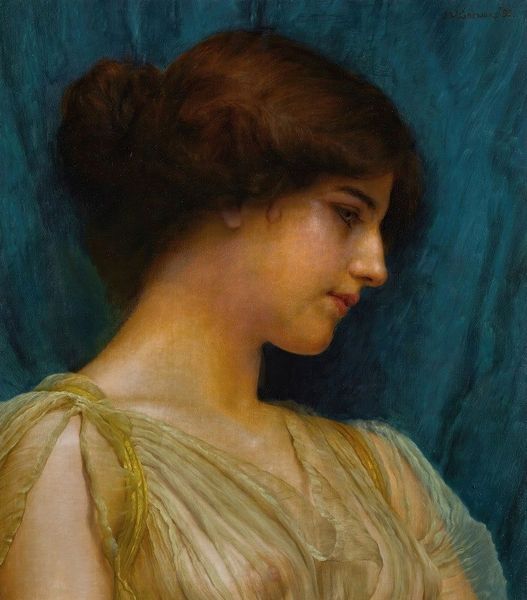

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: "Head of a Girl," also known as "The Priestess," painted by John William Godward in 1896. Editor: The softness of the light immediately strikes me. There’s a subtle use of oil paint to give the figure's skin and sheer clothing an almost porcelain-like quality, quite luxurious, actually. Curator: Luxurious and deliberately posed, yes. Godward was working within a late Romantic aesthetic and highly conscious of creating an idealized female form—the “priestess” title adds a layer of interpretation tied to patriarchal constructions of women and power within spiritual or mythical roles. Who has power, who gets named priestess, and why? Editor: That’s a crucial lens. I’m also considering the production itself. Oil paints in 1896 would have involved grinding pigments, layering, and glazing for that incredible luminosity. Someone mixed those colors; someone stretched that canvas. Curator: Precisely. And what about the audience intended for this level of technical skill? Godward sought acclaim and sales. What fantasies were being indulged by the predominantly male gaze of the art market? Is it a celebration or an objectification of women? Editor: Objectification for sure is part of this market transaction but celebration of skilled craft shouldn't be discarded that easily. Look closely at the metal leaves arranged in the subject’s hair; were those prefabricated or custom made by a metalworker? The detail speaks to high-end craftsmanship fueling artistic license. Curator: I agree about the value placed on the metalwork, but think about how such meticulous depiction can also serve to exoticize or stereotype the female subject—presenting her not as an individual but as an archetype within a romanticized vision of ancient societies, her identity almost erased by ornamentation. Editor: Right, we should both question who gets elevated through craft, who benefits economically, and whose stories get prioritized within this intricate dance between patron, maker, and muse. Curator: Ultimately, confronting this tension between visual appeal and underlying cultural assumptions can enrich our understanding of power and representation in late 19th-century art. Editor: A fascinating exchange around materials, labor and cultural context helps decode this seemingly uncomplicated piece.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.