etching

#

baroque

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 311 mm, width 396 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

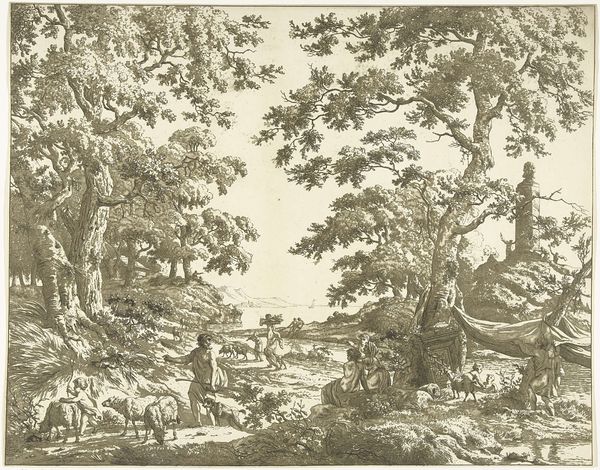

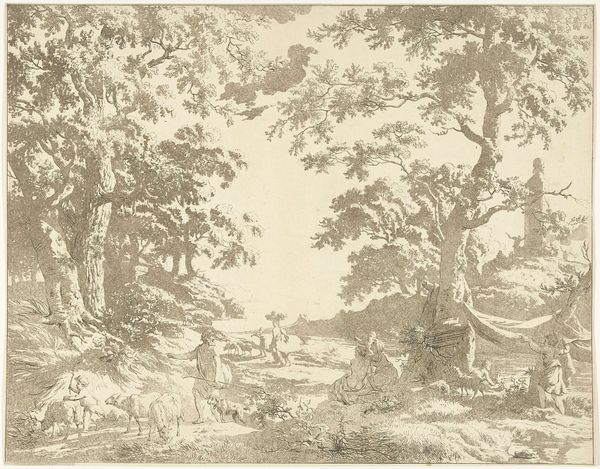

Curator: This is Franciscus de Neve’s “Tamboerijnspeelster,” or “Tambourine Player,” an etching dating from around 1660 to 1666. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first impressions? Editor: A pastoral scene bathed in quiet light. It appears serene but, under the surface, there's a tension in the very materiality— the delicate precision of the etching contrasting with the rugged naturalism depicted. How was something so precise mass-produced? Curator: Precisely! The image exists due to this controlled multiplicity. De Neve utilizes the linear quality of etching to emphasize structure, directing the gaze from the seated figure in the foreground toward the expansive landscape beyond. Editor: This focus overlooks the etcher's craft. The labor! To translate the idea of a landscape and its inhabitants into physical lines with acid on metal is a task with its own context. This isn’t just an image—it's an object borne of a process. It's a landscape captured through material labor. Curator: True, but note how the artist has staged this idyllic scene using tonal variations achieved through cross-hatching and varied line weights. These design elements are key, building layers of meaning through pure form and the inherent tension between foreground and background. Editor: What sort of meanings can come solely from form when the labor to produce an etching in the mid-17th century carried its own significance? The printmaker’s choices of line aren't abstract exercises, they’re embedded within a system of patronage and commerce. Who bought such scenes, and why? What were the material conditions of those consumers? Curator: We see echoes of Baroque landscape painting, stylized and idealized. But his mark-making suggests something further is happening, too: a certain resistance to complete resolution of the forms depicted; figures left a bit ambiguous in the chiaroscuro, foliage somewhat wild. Editor: That supposed ambiguity hints at something vital – that landscape paintings, etchings and so on, weren't viewed solely as art, but were products, bought and sold. Focusing solely on forms distances art from its function, from how it lived amongst the people of its time. Curator: Interesting point. Reflecting upon this image has made me newly consider that interplay between visual form and material context. Editor: Yes, it is always important to ground visual interpretation in historical labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.