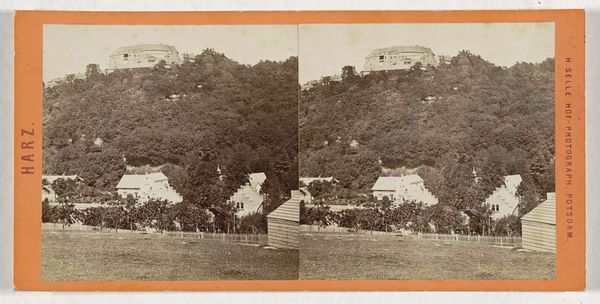

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

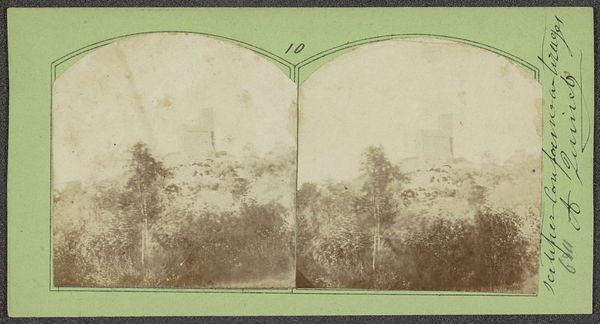

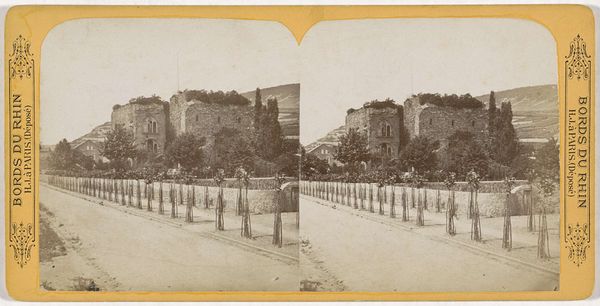

Curator: This albumen print, dating from between 1857 and 1863, presents a cityscape view of Bad Godesberg and the Godesburg ruins. The artist is Theodor Creifelds. Editor: There's a quiet melancholy about this. The muted tones of the albumen print evoke a wistful, almost dreamlike quality. The imposing ruin perched on the hilltop dominates the scene. Curator: The choice of subject matter speaks to the 19th-century Romantic movement's fascination with ruins and the past, key symbols in that period. Editor: Absolutely, you see it in the composition. The winding path leads our eye directly to the ruined castle, but I see a visual contrast between the pastoral scene with the path in the foreground, the modern buildings near the castle mount and the dark silhouette of the old stronghold in the background. Is it possible Creifelds used this visual game to emphasize progress and industry versus the fading past and an idealized era? Curator: A definite tension between eras, progress and historical weight. These photographic postcards became immensely popular as tourism and ideas of nationhood surged across Europe. To own or share such images shaped public engagement with Germany's political narrative, creating cultural connection that shaped national identity. Editor: And the castle ruin is not just a ruin—it's a powerful emblem. Think about its layered meaning for viewers at the time; standing in for history, certainly, the ravages of time. A possible religious symbol also given Godesberg name, hinting the stronghold to have been of ancient theological importance to inhabitants. I almost imagine that the scene and framing itself are like visual metaphors. Curator: This work is such a powerful indicator of the social context from which is sprung from. It shows, ultimately, how photography like this had an implicit role, subtly framing cultural memory within a visual language, and influencing public sentiment during that period. Editor: Indeed. Every viewing offers new questions to think about how imagery continues to weave collective meaning across generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.