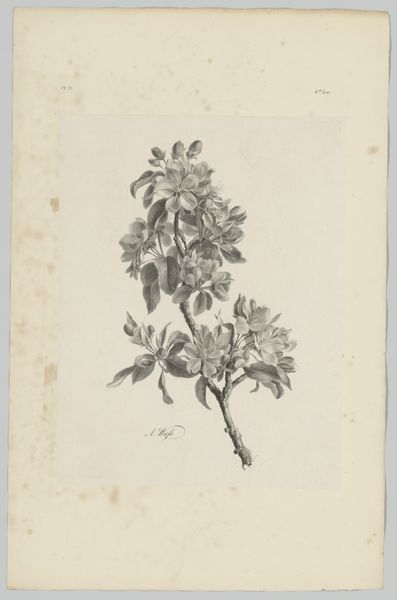

Dimensions: height 503 mm, width 334 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

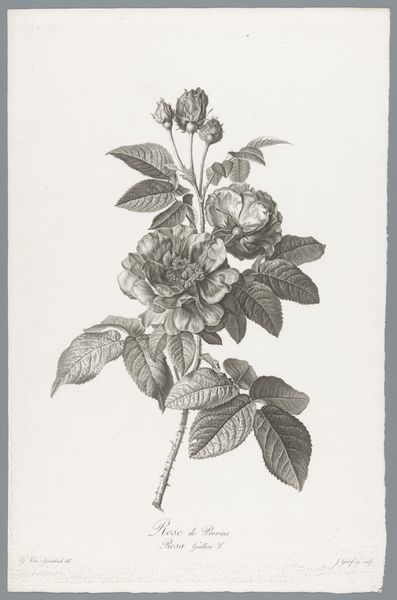

Editor: We're looking at "Honderdbladige Roos," or "Centifolia Rose," a print by Pierre François Legrand, dating from 1700 to 1801. It's incredibly detailed; the artist captured every vein on the leaves, and the thorns look so sharp. It evokes a kind of quiet elegance, doesn't it? What can you tell me about the context in which a piece like this would have been made and consumed? Curator: Certainly. Botanical prints like these flourished, literally, during a period of intense scientific exploration and classification. Remember, this is the era of Linnaeus, when naming and ordering the natural world became a major intellectual pursuit. But beyond pure science, this imagery intersects with colonialism. These botanical drawings weren't just records; they were also tied to resource extraction, mapping colonial territories, and even medicine. Editor: That’s a connection I hadn't made. So, these beautiful prints weren’t purely aesthetic or scientific… Curator: Exactly. Who had access to these images? What was the social and political role of understanding, classifying, and controlling nature? Consider who owned these prints, perhaps wealthy landowners managing their estates, apothecaries documenting medicinal plants, or even colonial officials sending information back home. The “rose” then becomes more than a simple flower; it's entangled in a complex web of power and knowledge. Editor: I’m starting to see the layers here, beyond just a pretty flower! This connects the art directly to the world outside, illuminating aspects of economics and politics. Thanks so much! Curator: And it’s worth noting, even in our current socio-political moment, these connections still have resonance as we examine environmental awareness, sustainability and cultural understanding. It’s been my pleasure!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.