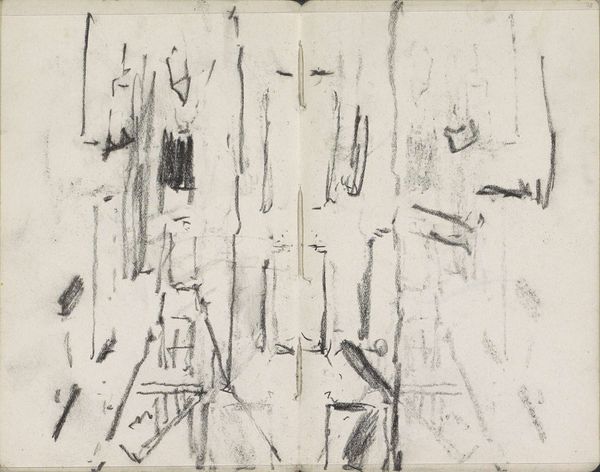

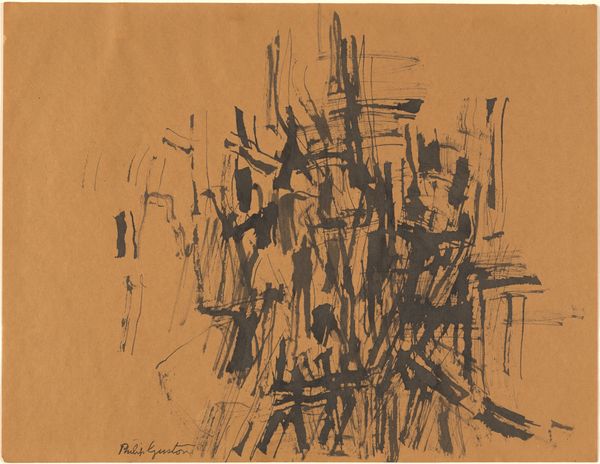

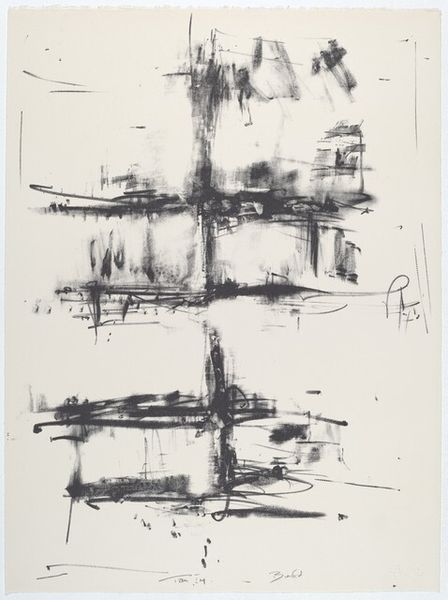

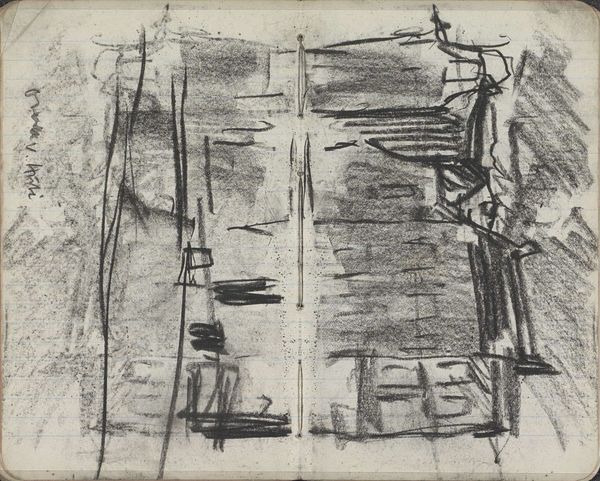

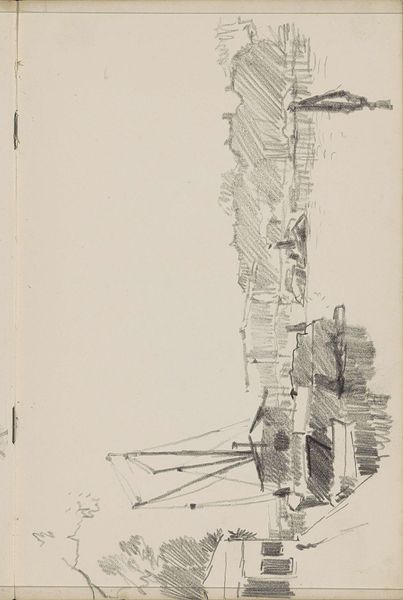

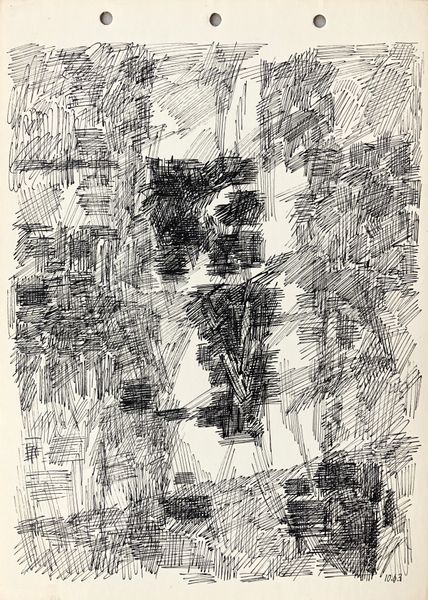

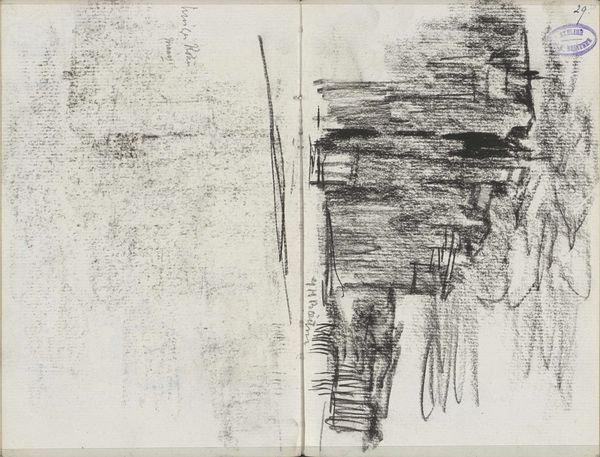

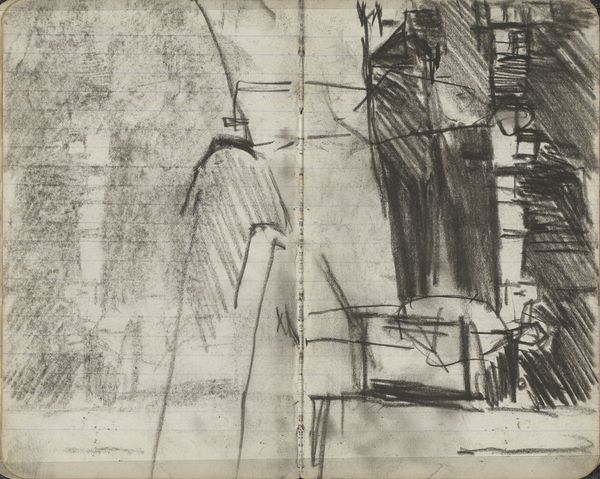

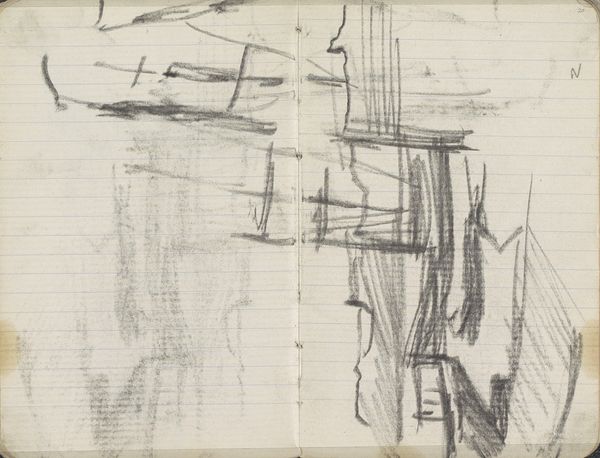

drawing, ink, pen

#

abstract-expressionism

#

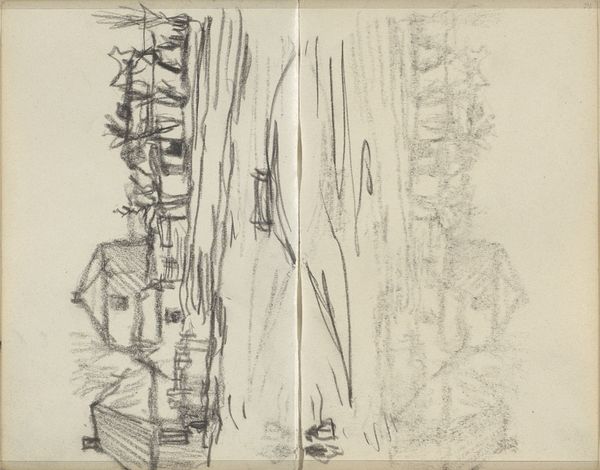

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

pen sketch

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

abstraction

#

line

#

pen

Dimensions: overall: 45.6 x 60.7 cm (17 15/16 x 23 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at this pen and ink drawing, I see a series of dark shapes floating on the surface, almost like scattered thoughts trying to cohere. What are your initial reactions to Philip Guston's "Untitled," created in 1953? Editor: I find it incredibly unsettling. The composition seems unstable, and the stark contrast of the black ink on the bare paper creates a sense of tension and unease. It feels like witnessing something fragmented and raw. Curator: And in considering the political landscape of 1953, particularly the rise of McCarthyism in the United States, could Guston's abstract expressionist work serve as a kind of silent protest against oppression, against the stifling of intellectual and creative freedom? The abstraction offers a means of expressing dissent without direct confrontation, which can be tied to the idea of art as a social commentary in a climate of censorship and surveillance. Editor: It’s tempting to see such socio-political intent behind the abstraction, but I wonder how much Guston consciously sought that path. This was, after all, during the apex of Abstract Expressionism's dominance in the art world. The post-war context promoted individualism, even escapism, in some artistic circles. Do you think Guston was overtly making a statement, or was this part of a broader cultural detachment in artistic communities at the time? Curator: I think that Abstract Expressionism always held potential for subconscious resistance because the gesture of making art without constraints becomes an inherently defiant act when social and political controls intensify. Furthermore, thinking of Guston’s later move away from pure abstraction, could this then be understood as him realizing the limitations of abstraction as political language? Editor: It is interesting how the institutional history then situates this period as both innovative and as potentially lacking clear social purpose in comparison to other eras of more direct art activism. Did museums promote this abstraction to distract from social realities, or to promote some sense of intellectual and artistic freedom at the time? Curator: That question speaks directly to the relationship between art, institutions, and society! I believe this work presents us with a compelling lens to scrutinize not just art history but the cultural and political forces that underpin artistic expression and interpretation. Editor: And for me, thinking through all the questions you’ve brought to light, this piece becomes an open call to excavate art’s subtle dialogues with social conditions and power dynamics. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.