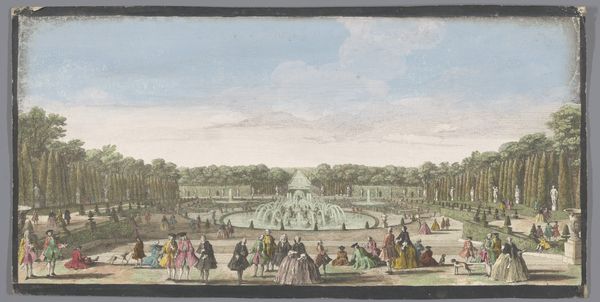

Gezicht op het Bosquet des Dômes in de Tuin van Versailles after 1691

0:00

0:00

jacquesrigaud

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 238 mm, width 477 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, I'm struck by the opulence and almost theatrical quality of this scene. It’s quite a production. Editor: It truly is. This is Jacques Rigaud's "Gezicht op het Bosquet des Dômes in de Tuin van Versailles," made sometime after 1691. Rigaud captured it using watercolors, colored pencils, en plein air, as was his method, resulting in a remarkable landscape drawing of the estate. What do you make of Rigaud's chosen mediums and technique here? Curator: Well, the watercolor application feels intentional—the artist is choosing to give it an ephemeral or dreamlike feel; these materials really speak to that sort of atmospheric quality of the scene itself, right? I'm wondering about how he managed to depict this level of architectural detail outdoors, which seems to contrast this material delicacy. What do we know about Rigaud himself? Editor: Rigaud, coming from a family deeply involved in drawing and printmaking, made a name documenting royal properties, so we're seeing the machinery of image-making and power all bound up together here. I can't help but consider Versailles' symbolism here: how does it function as a representation of both Louis XIV’s absolute authority and the profound social stratification of the era? Curator: Precisely. The very act of commissioning such elaborate drawings like these speaks volumes about the King’s desire to display absolute command of land and resources, including the artists creating these drawings! Editor: The people almost become part of the ornamentation, mere spectators in this display of power and artifice. Do you find anything interesting about the labor required to realize and maintain such art, not only the artwork but also the gardens themselves? Curator: Absolutely, we’re considering everything: the physical act of landscaping, sourcing, irrigation, but also this social aspect – the spectacle of wealth! The drawing captures labor that is often invisibilized: both of garden staff and the artist that needs patronage in order to survive. Editor: By positioning art making as labor and thinking about the social life that is present in Rigaud's choice of making this 'view,' we’re not only reflecting on the world as Rigaud presents it but also on the conditions that render such a vision possible. Curator: And perhaps in considering that, we come to terms with both Rigaud's material choices and our own positions as viewers engaging with history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.