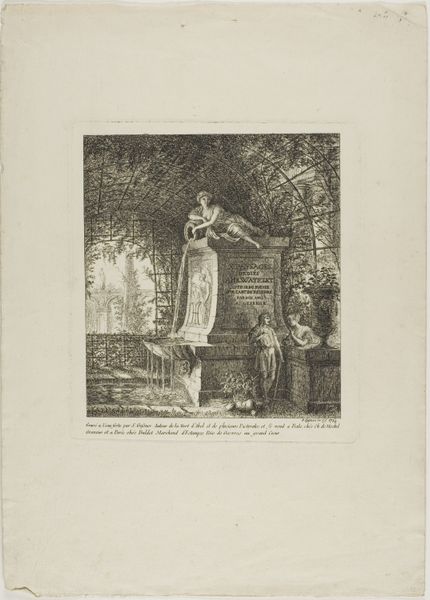

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

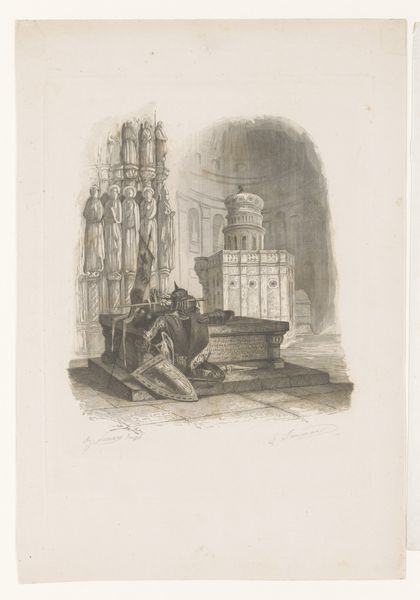

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

#

pen drawing

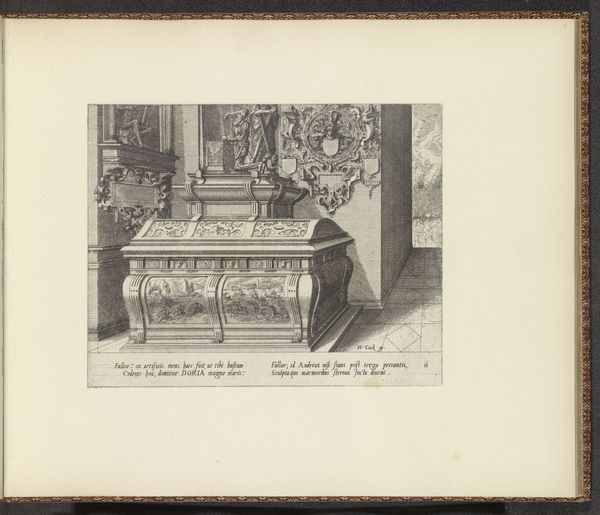

# print

#

ink

#

engraving

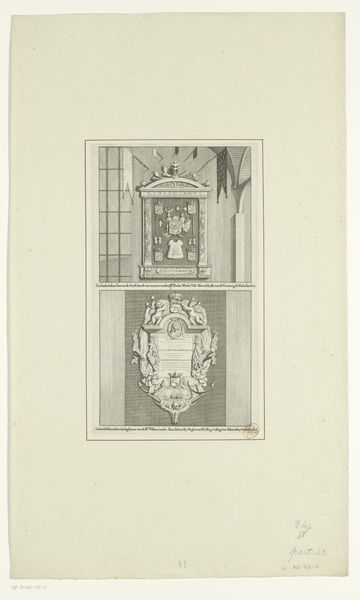

Dimensions: height 285 mm, width 230 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving from 1848 by Carel Christiaan Antony Last is titled "God behoede Nederland," or "God Save the Netherlands." It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. What's your initial take? Editor: Grim. Visually arresting, of course, with the sharp lines of the engraving. Death seems to be staging a rather theatrical performance. The Dutch Lion appears vulnerable here, indeed. Curator: Absolutely. The symbolism is rich. The figure of death sits at what appears to be center stage holding a scythe. There is an hour glass next to him, emphasizing mortality. Look closely at the Dutch Lion represented here with its paw resting on a stack of papers and looking quite ill, no? What elements of this tableau really grab your attention from a cultural history angle? Editor: Well, given the date, 1848, this resonates deeply with the anxieties of the time. Revolutions were erupting across Europe, threatening established powers. The Netherlands, while ultimately spared the widespread violence, was not immune to the tremors of political and social change. Curator: Right, you can feel that. Notice the figure of death seemingly about to pull the curtains? One might read this work as the Netherlands confronting its own mortality. The "God Save the Netherlands" title acts as a cry, or a plea against political or perhaps even literal dissolution. What lasting imagery resonates with you? Editor: I’m drawn to the architectural backdrop—the stone wall and archway. It lends a sense of imposing history and established order that feels threatened. And those ribbons hanging across the table... grim documents. Curator: Precisely. There is a certain stoic resilience despite alluding to disruption. The inclusion of "Bethel," meaning "House of God" as it's written in Hebrew on the lintel reinforces both vulnerability and potential for grace. What visual traditions do you see informing this work? Editor: The neoclassical style lends an air of gravity and classical precedent—an attempt, perhaps, to frame the turmoil within a historical context, giving it both weight and a sense of inevitability but also an appeal to reason amidst the chaos. Curator: It seems Last has created more than just a political statement. It’s a visual manifestation of national vulnerability, crafted in the symbolic language of the time. Thank you for your insights, it brought it to life. Editor: Indeed, seeing it through the lens of political unrest certainly makes one reflect on how much fear can shape visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.