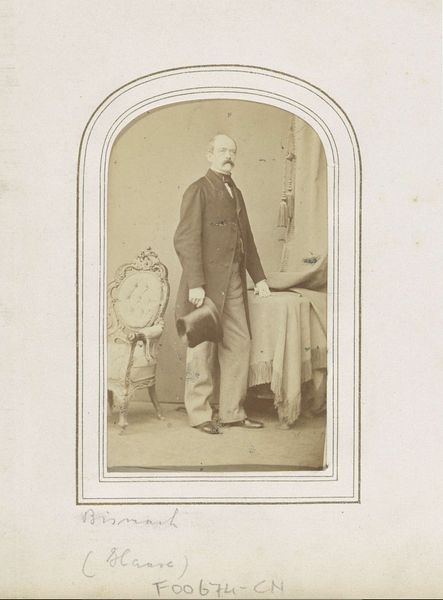

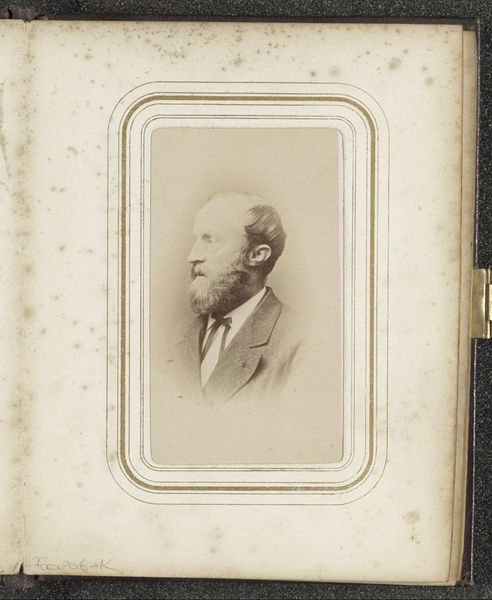

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This striking photograph from 1865, titled "Fotoreproductie van een portret van een man," comes to us via Woodbury & Page, captured utilizing the albumen print process. What strikes you initially? Editor: Well, it’s undeniably formal. The man’s attire, the composed pose… it all suggests a deliberate presentation of status and respectability. The framing enhances that, giving it a staged, almost theatrical feel. Curator: Indeed. Consider the albumen print process itself. Creating these prints involved coating paper with a solution of egg whites and silver nitrate, rendering images of exquisite detail, especially prized for portraiture in that era. Each print becomes a tangible document of the sitter’s likeness, elevated through meticulous chemical procedures and physical craft. Editor: Which underscores its purpose, I think. Photography was still relatively new, but quickly becoming democratized, even though posing for a portrait was a statement in itself. It represents more than just an image of this particular man; it tells us about social aspirations, about the rise of photography and its use as a tool for self-representation within that society. This type of portrait became part of the Victorian social fabric, almost a cultural rite. Curator: The subtle tonality achieved via albumen prints surely impacted how viewers then and now would interpret this person and this genre. The choices involved – the photographic materials themselves and what those afford technically—shape our perception of the subject depicted, shifting photography from a mere reproduction of likeness into something entirely considered and composed. Editor: Absolutely. This portrait gives us a glimpse of how people sought to project themselves within the conventions of their time, and it's fascinating to see how the choice of photographic process played a role in this construction. It’s not just a face; it’s a story of societal values etched onto a tangible object. Curator: It’s intriguing to think how future historians will continue piecing together the narrative of 19th-century society using examples of crafted portraits, particularly focusing on the materiality itself to reconstruct ideas surrounding access, agency, and consumer culture in the burgeoning days of commercial portraiture. Editor: Agreed. Seeing how a seemingly simple image acts as a cultural artifact helps deepen our understanding. The history of the piece is revealed both in the figure presented and in the object in itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.