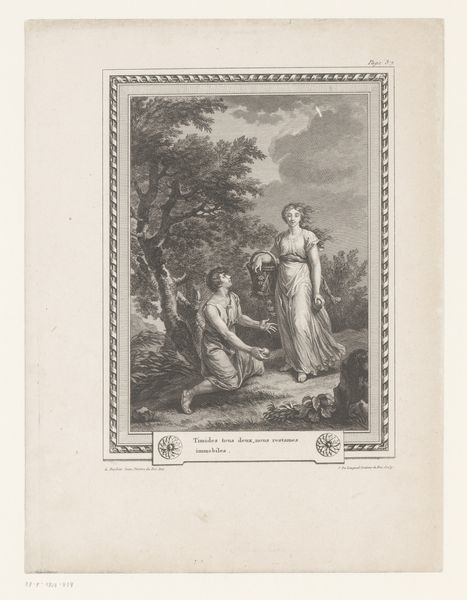

Dimensions: height 300 mm, width 213 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

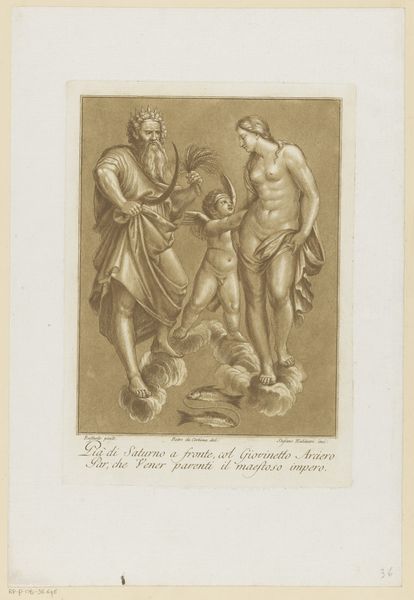

Curator: The piece before us is a print, an engraving actually, entitled "Diana en Callisto" by Stefano Mulinari, estimated to have been created sometime between 1751 and 1790. It looks to me like an illustration referencing a famous mythological scene. What is your impression as you look at it? Editor: Well, it's got a rather serene quality to it, despite the dramatic potential of the subject matter. Everything seems to be floating gently, suspended in time. Is that shame I see on the right or merely cold air against the skin? I do find the almost monochromatic rendering to be captivating, it mutes some of the story's sharpest angles and transforms it into something timeless, and maybe a little melancholic. Curator: That’s an astute observation, its execution is indeed remarkable. It’s worthwhile considering its placement within a larger framework of evolving social values as this print presents the scene of divine judgment of the chaste huntress Diana upon discovering that her nymph Callisto is pregnant after being seduced by Zeus, the god king. The judgment that ensues reflects larger views about women, transgression and justice circulating in society at the time. Editor: Absolutely, I read that judgment but almost a different thing altogether. Doesn’t Callisto look more embarrassed, even burdened than inherently "shameful?" Diana’s the real cipher here – her cool removal practically throws the imbalance into neon relief! Perhaps society wasn’t so fixed then either and more in dialogue than we give them credit for… Curator: Yes, exactly. How Mulinari chose to interpret and visually present the well-known narrative reveals, or perhaps even subtly challenges, those prevailing viewpoints within a very particular social and political climate. That’s a key component of why history painting, like the example we’re observing today, held such importance as vehicles for social commentary during the Baroque period. Editor: It becomes this muted conversation that trickles down, a story whispered across generations through each reproduction, altered yet oddly resonant across eras. Thinking about all those countless eyes interpreting those lines... I'm compelled to appreciate the power residing in an object such as this one today. Curator: Yes, this unassuming engraving presents many things, acting as a portal through which we observe art, the socio-cultural moment that bore it, and, of course, ourselves. Editor: It's strange to be discussing art this way when something seemingly very classic can simultaneously whisper about liberation... from all of the stuff.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.