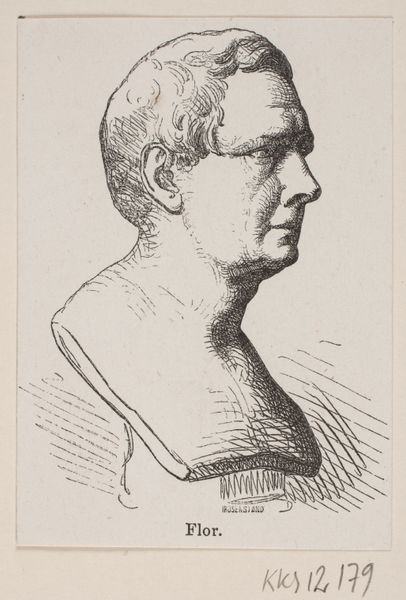

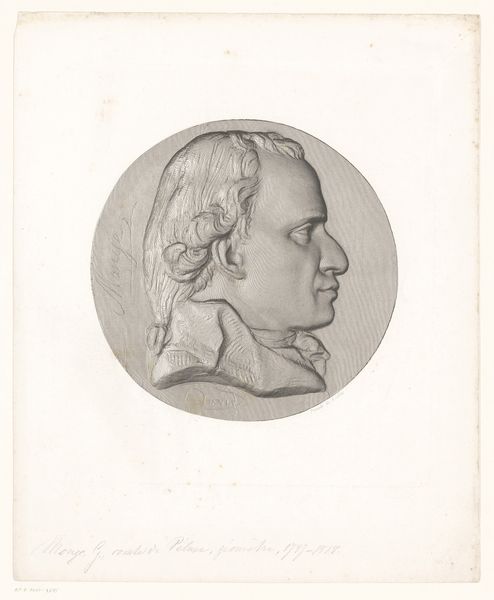

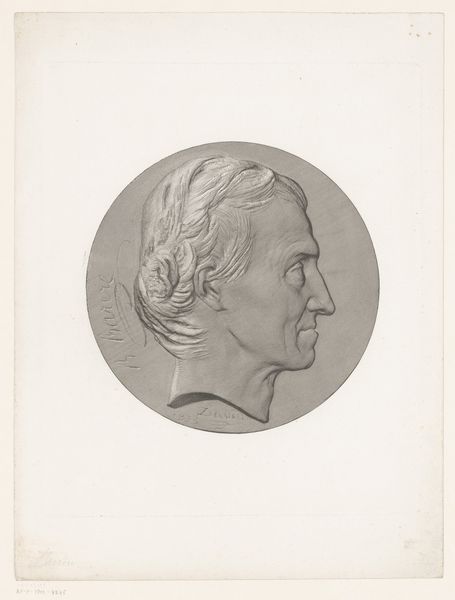

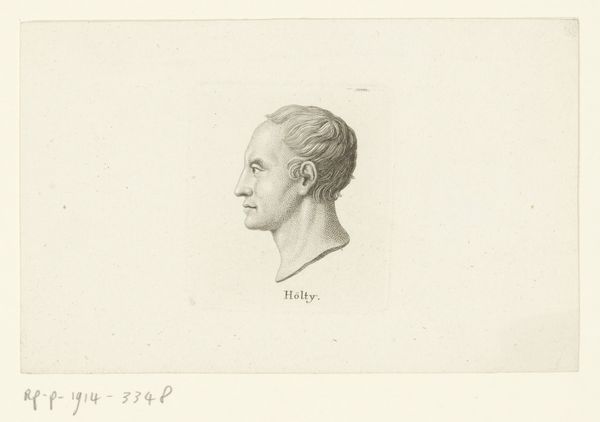

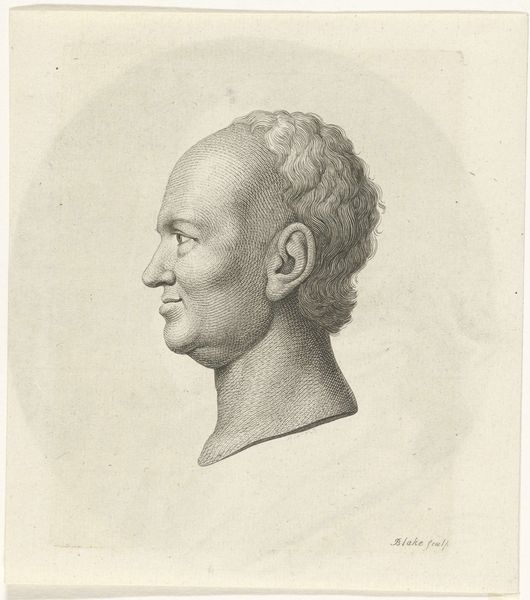

print, woodcut, engraving

#

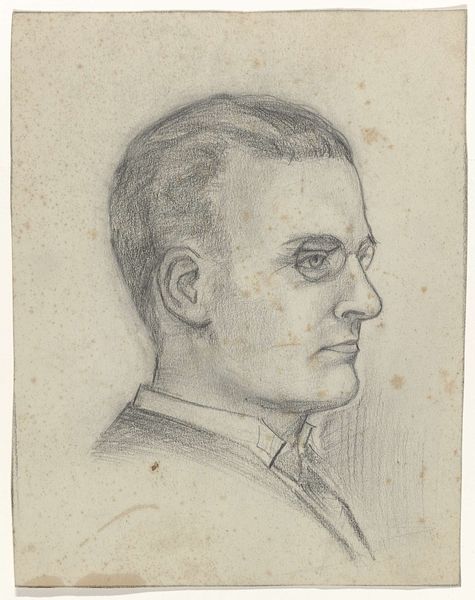

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

woodcut

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: 150 mm (height) x 105 mm (width) (bladmaal)

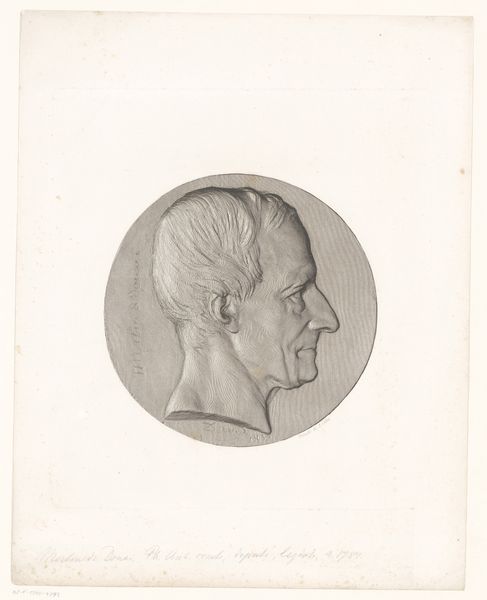

Curator: Looking at this work, "Henning Johan Peter Schouw," created sometime between 1826 and 1893 by H. C. Henneberg and currently residing at the SMK, what strikes you first? It's a portrait rendered as a print, through either woodcut or engraving techniques. Editor: The starkness, really. It feels immediate, almost like a quickly executed political cartoon, though perhaps a bit more refined. The contrast of light and shadow emphasizes the subject's... resolve, shall we say? Curator: Absolutely. The visual language suggests more than a simple depiction; it is a portrait laced with potential social commentary. Schouw lived through tumultuous political times in Denmark. How do you see the materials contributing to its message? Editor: Well, the choice of printmaking itself—likely a woodcut or engraving—implies a wider circulation than a unique drawing. This immediately situates it within the context of reproducible media, accessible to a broader audience, perhaps as illustration in pamphlets or newspapers of the time. It speaks to the democratization of the image. Curator: Exactly. And consider Schouw’s background, particularly within scientific discourse. A disseminated image like this plays into shaping and perhaps solidifying his public persona, but maybe with some bias or agenda? Editor: It’s fascinating to consider the labor involved, too. Someone had to meticulously carve those lines into wood or metal. That act of slow, deliberate creation imbued with political motivations, then multiplied across numerous prints changes the meaning. It shifts it from a simple portrait to a consciously manufactured image. Curator: The artist really makes every line work to create form, and even the negative space gives the artwork strength. But the choice of reproducible media and the probable reach of this portrait make us reconsider the intentions and impacts in disseminating the portrait. Editor: Looking at it through the lens of materials and processes really brings the social and historical implications into sharper focus. It underscores how images are manufactured and circulated within power structures. Curator: Indeed, it reminds us that even the simplest portrait can hold layers of meaning when you consider its context and material history. Editor: Precisely. And by understanding those layers, we gain a more nuanced understanding of both the art and the society that produced it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.