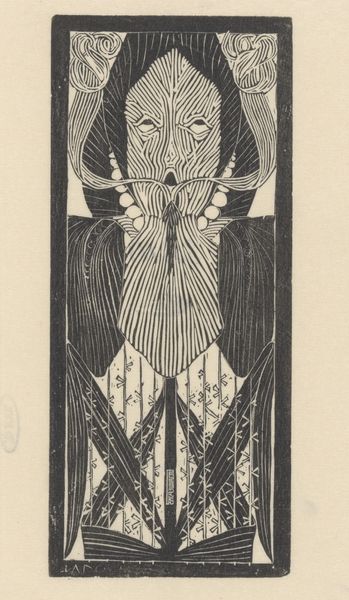

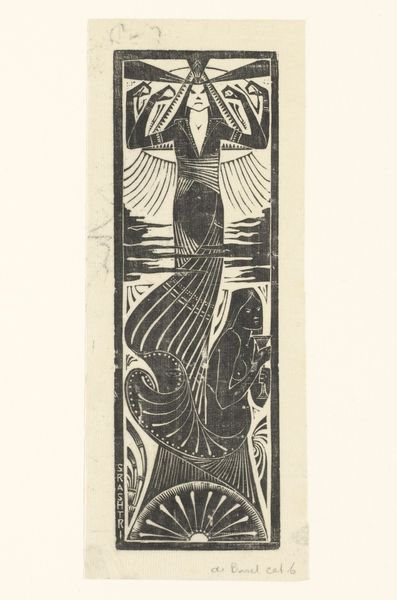

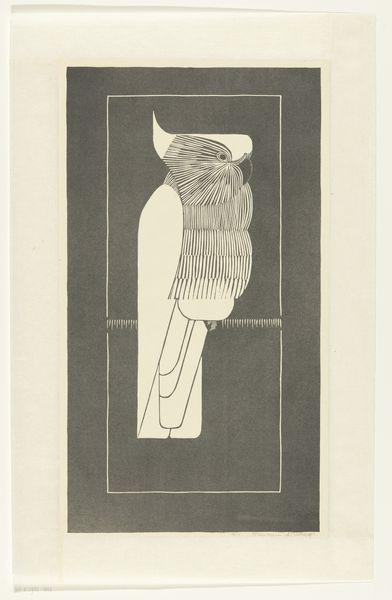

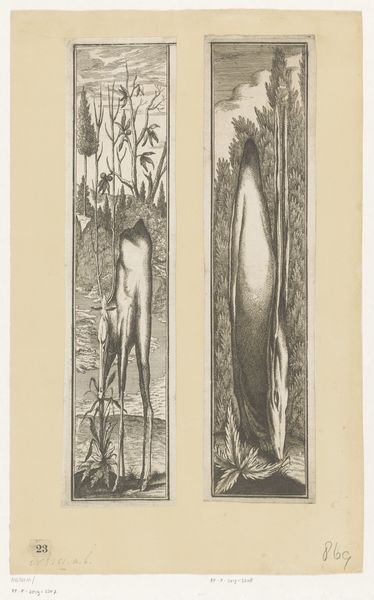

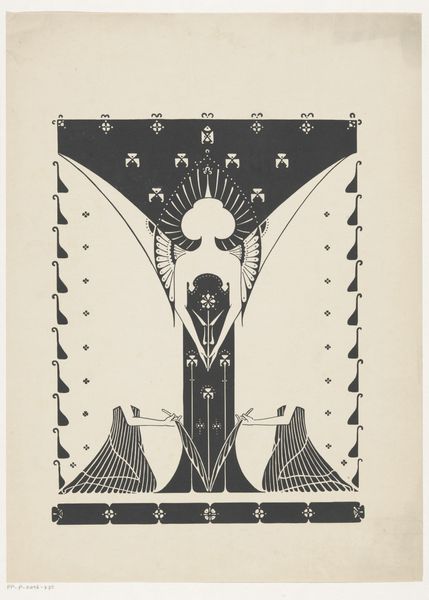

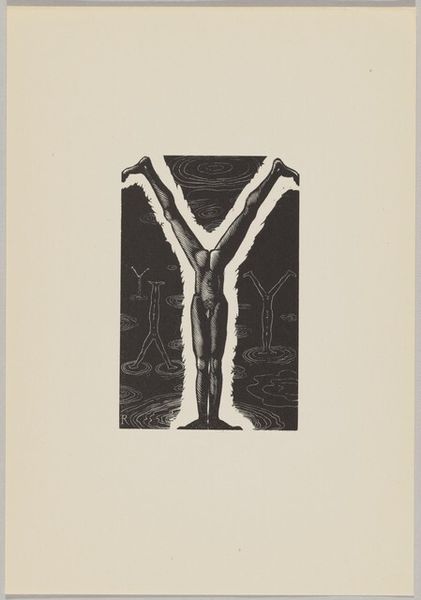

graphic-art, print, woodcut

#

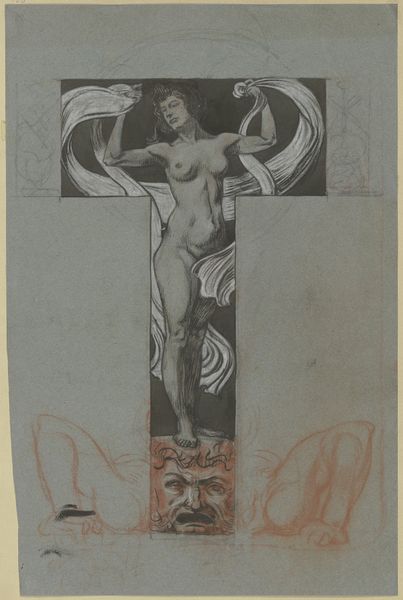

graphic-art

#

art-nouveau

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

nude

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 70 mm, height 295 mm, width 229 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There's a certain starkness to this piece, wouldn’t you agree? It's a woodcut, printed on paper, titled "Vrouwenfiguur" – "Female Figure" – made by Chris Lebeau sometime between 1888 and 1936. That elongated body and geometric patterning... I don't know, I find it profoundly unsettling, almost… spectral. Editor: Spectral, yes, but there’s a reclaiming happening too. This isn't simply a nude; it's a deliberately stylized figure within the context of Art Nouveau. We need to consider how women's bodies were being deployed and controlled in that era, especially concerning ideas around decoration and nature. Curator: Decoration and nature? I suppose the flowing lines and the floral motifs at the base evoke that. But look at the harsh contrast. It's as if she’s emerging, or maybe being swallowed, by the shadows. Is it strength, or imprisonment, you see in that pose? Those arms are rigidly horizontal. Editor: That tension between imprisonment and power is key. The rigidity of her stance is an active challenge to conventional notions of female passivity. Lebeau’s choice of woodcut – a very direct, almost brutal medium – speaks to that assertion of self. I wonder about Lebeau's own politics here? What can we read into the stylization and objectification of women’s bodies? Curator: It's intriguing you see brutality in the medium itself. I see it more as a vulnerability. All those sharp lines, the limited tonal range – it feels almost painfully exposed, like laying bare the artist's own struggles with form and identity. Almost confessional. Editor: I think both interpretations can hold. This interplay is really the point: Lebeau pushes us to question our assumptions about the female form. This stylized body refuses simple categorization, and its haunting ambiguity encourages the critical viewer to consider larger political ideas surrounding the treatment of women in that era, as well as today. Curator: Well, I'll carry that unsettling ambiguity with me. Makes you look at how art carries both the maker’s mark, and a heavy history too. Editor: Precisely. It’s in that friction we begin to understand ourselves and society a little bit better. And perhaps, become activists ourselves in a way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.