Dimensions: image: 380 x 260 mm

Copyright: © Neville Gabie | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Editor: This is Neville Gabie's "Van Reenens Pass," a photograph of a desolate football pitch. There’s something haunting about the solitary goalpost in such a barren landscape. What story do you think this image is telling? Curator: It speaks to the legacy of colonialism and imposed structures. A football pitch in a place called Van Reenens Pass? Who decided this field needed a goalpost, and what does it signify in this vast, seemingly untouched space? Editor: So, the image is less about football and more about power dynamics? Curator: Precisely. The photograph invites us to question who gets to define space, and for what purpose, within a broader narrative of cultural imposition and transformation. It asks, 'Whose game is being played here, and at whose expense?' Editor: I see it now! Thanks for opening my eyes to that.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 2 months ago

⋮

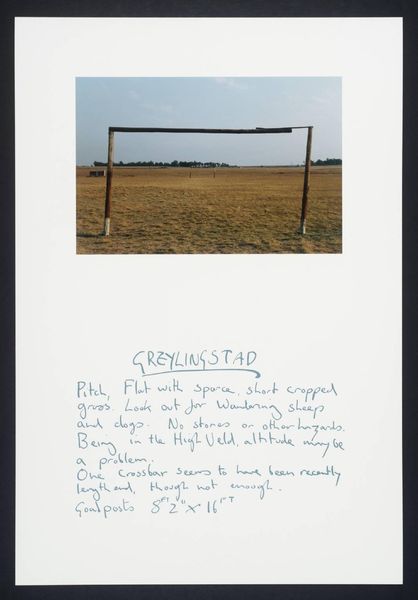

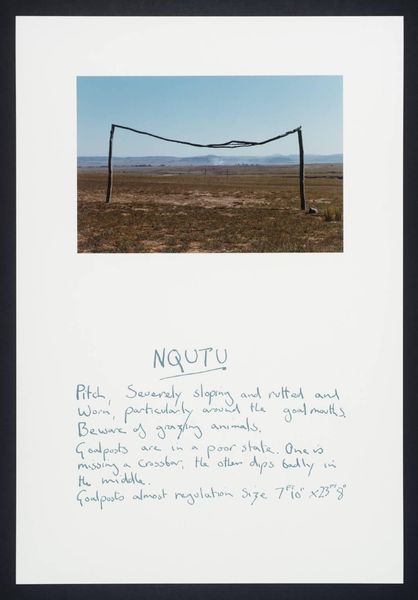

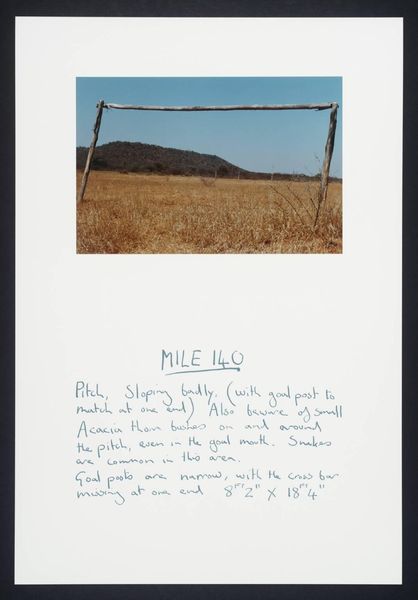

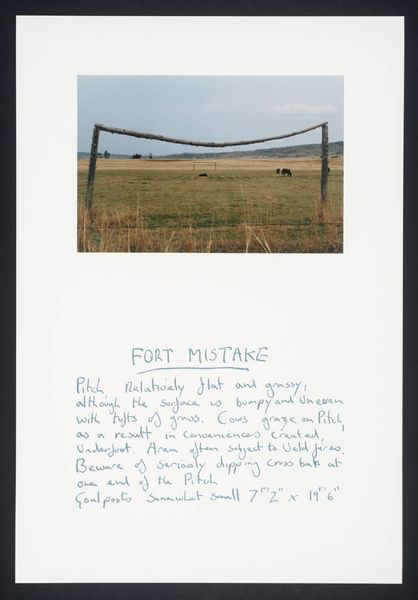

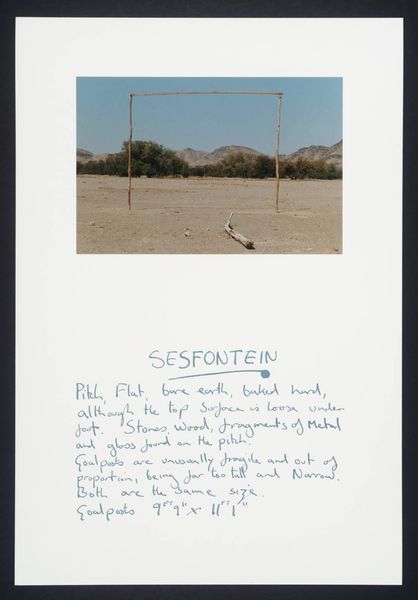

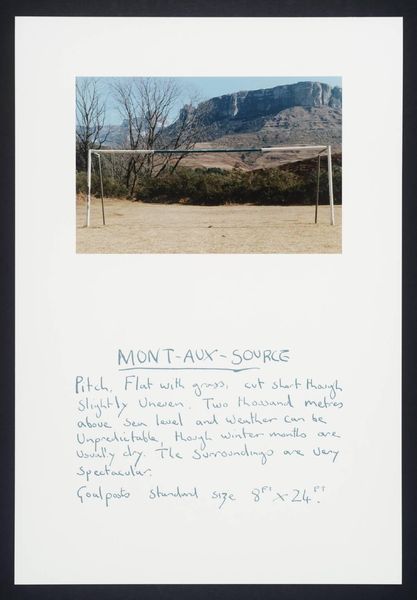

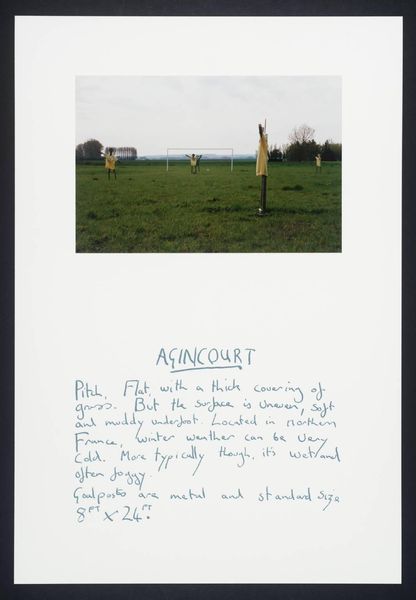

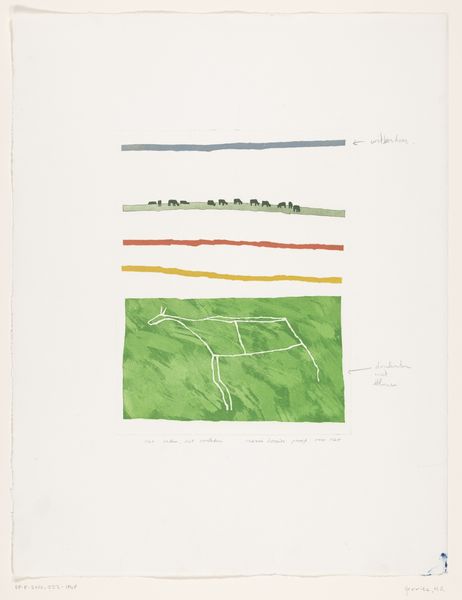

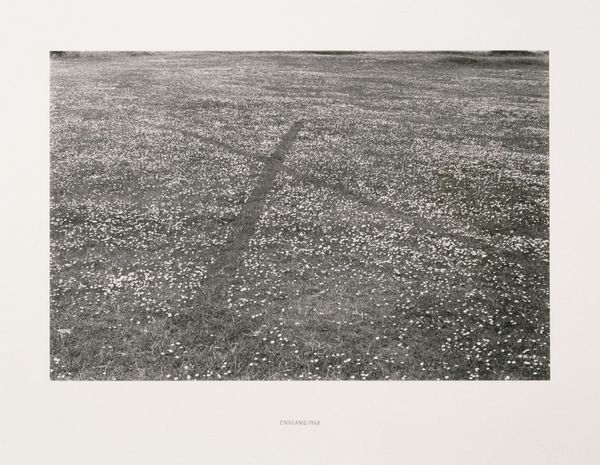

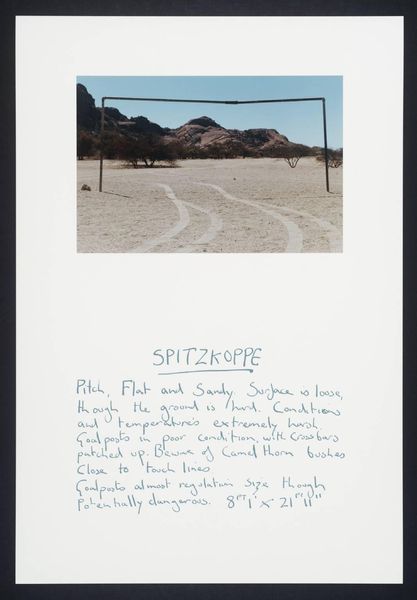

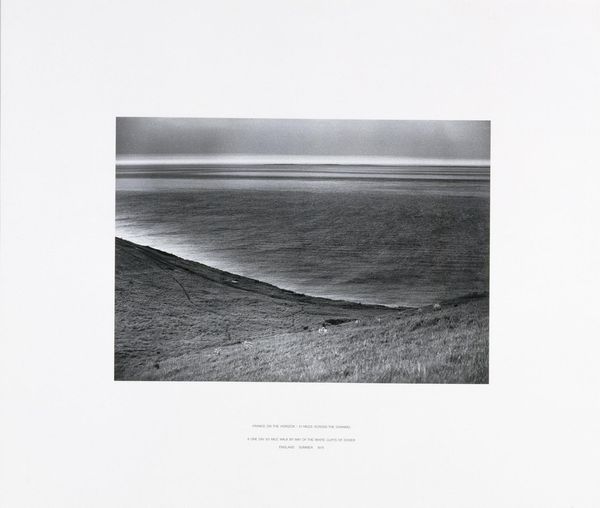

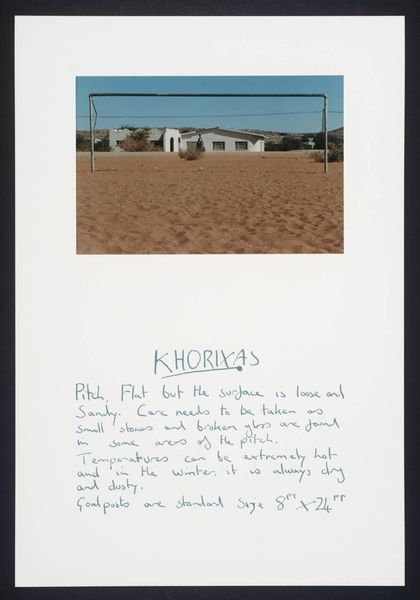

In 1998 Neville Gabie travelled around the world taking photographs of different kinds of football pitches. These varied from makeshift poles erected on dusty plains to the sophisticated stadiums of capital cities. He published these photographs in a book called Posts (London 1999). In 1999 he was awarded the tenth Momart fellowship at Tate Liverpool, where he worked on a print series related to the Posts photographs. The result was the portfolio Playing Away which was displayed at Tate Liverpool at the end of his tenure. Playing Away consists of twenty-four prints. The first twelve prints of the group show photographs of football pitches in South Africa. Many of the pitches are just a pair of wooden goalposts standing in undeveloped desert or mountain areas: the simplicity of the structures contrasting with the impressive scenery. Beneath the photographs Gabie has screenprinted the names of the locations and added notes about the condition and size of the pitch. To accompany the photograph of an arid pitch at Nqutu, Gabie notes: 'Pitch severely sloping and rutted and worn, particularly around the goalposts. Beware of grazing animals.' He adds 'Goalposts almost regulation size 7'. The last print in this group shows a lush, green western-style pitch which was photographed in Agincourt, France. Agincourt was the site of the historic battle waged and won by Henry V of England against the French in 1415; the battle was immortalised in William Shakespeare's famous play Henry V (c.1598). In this play Shakespeare looks at issues of honour and chivalry in warfare and compares the rules and etiquette of sport with those of battle. The play also evokes the complexity of nationhood and national allegiance. The other twelve prints in the portfolio combine a sketchy drawing of a football pitch, which Gabie found on a street pavement in Durban, the phrase 'dribble and pass' in eleven official South African languages and a quotation from Shakespeare's play Henry V. This group must be shown in an ascending order: each print has an extra mark which cumulatively builds up the image of the markings on a football pitch. The quotations also run in the order that they appear in the play. The final print in this group reveals the complete image of the football pitch and has the French phrase 'La Partie est Jouée' which means 'the hand has been played' or 'the game is over'. Gabie was born in South Africa and he notes on the contents page of this portfolio that it marks 'South Africa's first ever qualification to the World Cup Finals at France 1998'. Gabie draws parallels between the battlefield as the traditional site of racial conflict and the modern football field which has become a sanctioned ground of racial competition. Sport acts as a potent symbol of national identity, and South Africa's inclusion as a team in the 1998 World Cup invokes the country's new unity. However Gabie's use of 'eleven official South African languages' also reveals the complexity of national identity and unity. South Africa is a country with many different languages and racial groups, and each match in that country plays out in microcosm the racial tensions of the international World Cup. Although football is a global game, Gabie's photographs of the ad-hoc pitches in South Africa may also comment ironically on the disparity of wealth and opportunity that the sport generates around the world. Further reading:Neville Gabie, Posts, London 1999Merseyside Arts Magazine January-February 2000 Jemima MontaguApril 2001