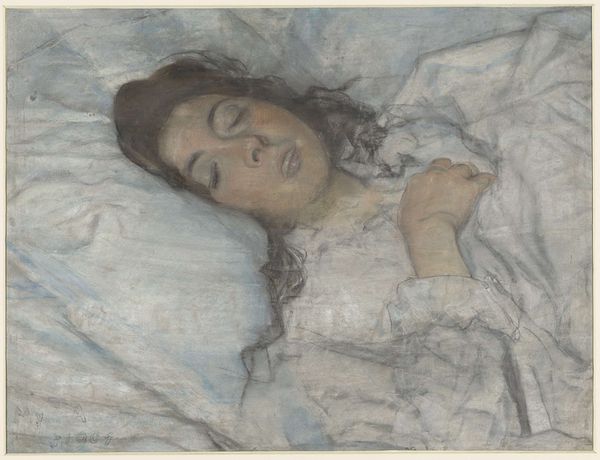

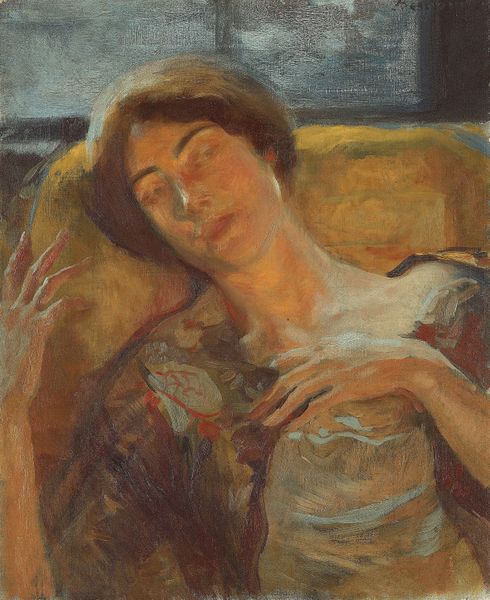

The Convalescent (A Portrait of the Artist's Wife) 1872

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet: 18 3/8 × 17 3/8 in. (46.7 × 44.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ford Madox Brown created this pastel drawing in 1872, a portrait of his wife titled “The Convalescent.” It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s so soft, so delicate. The palette is subdued, lending it a quiet, melancholic atmosphere. You immediately sense the frailty depicted. Curator: Absolutely. Brown employed pastel and pencil to create an intimacy. We must consider the role of domesticity and care labor in this period; the artwork reflects the Victorian era’s emphasis on sentiment and the portrayal of women within the confines of the home. Editor: And her red hair – likely rendered using colored pencils mixed with pastel – hints at vibrancy, perhaps suggestive of a spirit struggling against illness and reflecting how Victorian beauty ideals intersected with health anxieties. Curator: It's also worthwhile examining the texture of the paper he chose. Note the subtle tooth that grips the pastel, creating a slightly granular surface. This roughness enhances the impression of vulnerability. What can it tell us about available supplies during the Pre-Raphaelite movement and his selection process? Editor: Interesting point about access. And when we consider the symbolic dimension, those small flowers she's holding gain significance. Are they symbols of hope, remembrance, or the fleeting nature of life itself? Brown lost his first wife, Eliza, quite early. So is there also, perhaps, something of a romantic idealization here? Is that sentiment echoed or complicated by this re-marrying into a potentially fraught dynamic? Curator: That history significantly frames our understanding. Let's not forget, though, the material cost of pigments and paper, which dictate the scale and format of such personal pieces. These considerations affect which artists could practice freely in this moment. Editor: Yes, placing this piece in a social framework unveils the personal toll on women expected to bear societal burdens with silent grace. I also wonder about her own gaze, diverted elsewhere even while facing us directly. Her passivity also raises interesting conversations about access to healthcare, Victorian women’s rights, agency, and female representation. Curator: Brown uses his mastery of pastel application to imply a tangible reality while simultaneously invoking the ephemeral. Understanding these elements, we start seeing beyond mere surface, examining Victorian culture’s production means that have brought us this scene today. Editor: Yes, through our discussion, we uncover layers of meaning. Her fragility becomes less a symptom of simple illness and more a statement regarding the burdens women carried during that period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.