drawing, metal, sculpture, wood

#

drawing

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

15_18th-century

#

wood

#

decorative-art

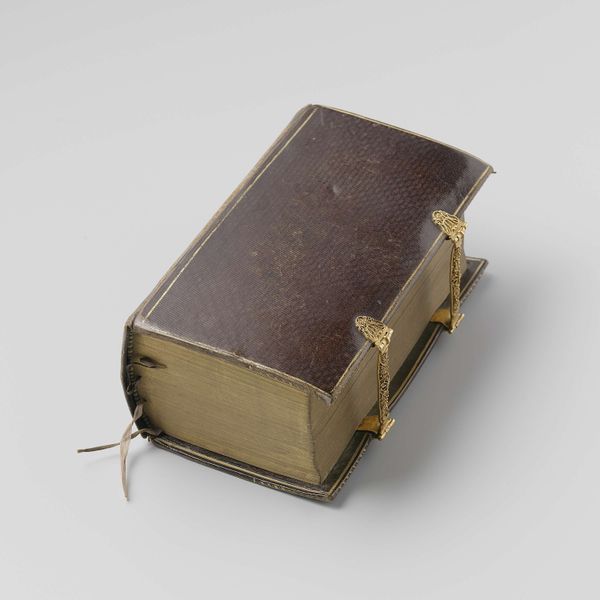

Dimensions: Case: H. 7 x W. 3 1/8 in. (17.8 x 7.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is a pocket set of drawing instruments created by Peter Dollond sometime between 1750 and 1765. It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is the elegance and apparent miniaturization. The tools glint, even from here, and the speckled green of the case makes me think of an exotic beetle. Curator: I see in this set a reflection of the 18th-century desire to quantify and map the world. These aren’t merely tools; they symbolize the pursuit of scientific understanding through visual representation. Notice how each piece is carefully wrought from wood and metal; they fit snugly within the case, reminiscent of sacred relics or tools one might use to approach God through geometry. Editor: And that brings me to the means of production. Peter Dollond was renowned, and clearly his craftspeople were skilled. The division of labor is fascinating here: consider the procurement of materials like shagreen for the case – possibly from shark skin – alongside the specialized labor needed to fashion each instrument with such precision. Were these destined only for the wealthy? Did such sets democratize draughtsmanship at all, or serve primarily as status symbols? Curator: Absolutely, access to such refined instruments would have been restricted. However, I also contemplate the larger symbolic weight: drafting instruments in themselves signify not only knowledge, accuracy and perspective but also an attitude of power and the drive of mastering representation of knowledge. Someone carrying this kit in their pocket signaled their embrace of Enlightenment values. Editor: But doesn't this fetishization obscure the physical reality, the labor inherent in creation? The comfort of the owner of these materials comes at the cost of other craftspeople around the world involved in resource extraction and manufacturing. It’s not just about personal Enlightenment; it is about broader production networks, market hierarchies, colonial resource acquisition. Curator: An incisive point. It complicates our interpretation by linking it to the less visible underbelly of eighteenth-century global exchange, underscoring a complex interplay between symbol and materiality. It is not merely an attitude of power, but the tools of material and political dominance. Editor: Exactly! So, looking again, beyond their geometrical potential, I find I’m drawn into the messier histories of manufacture, and even extraction. These instruments aren’t only about scientific precision; they tell silent stories of labor and resource exploitation. Curator: I will be contemplating the relationship between knowledge and authority differently. It casts the allure of such crafted sets with a new complexity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.