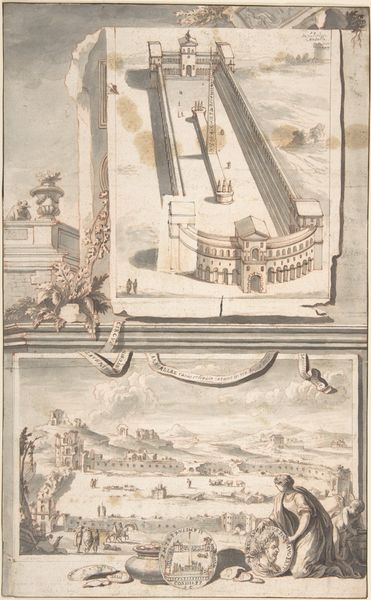

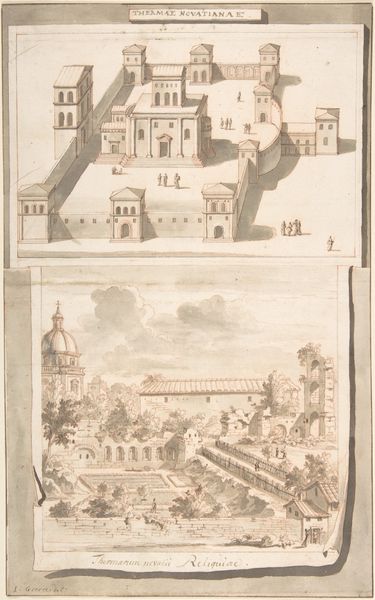

A View of the Obelisk and Saint John in Lateran (above) and a View of an Egyptian Site (?) (below) 1690 - 1704

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, ink, pen, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

ink

#

pen work

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

italy

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

building

Dimensions: 13 3/16 x 8 1/8 in. (33.5 x 20.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This intricate drawing, "A View of the Obelisk and Saint John in Lateran (above) and a View of an Egyptian Site (?) (below)" by Jan Goeree, dating back to 1690-1704, really struck me. It’s done in pen, ink, and engraving. The stark contrast between the detailed cityscape above and the more ambiguous, fantastical scene below is quite jarring. What do you make of this diptych, especially its seeming fascination with obelisks and monuments? Curator: It’s a fascinating visual document of its time. Remember, in the Baroque period, prints weren't just art, they were also vital for disseminating information and shaping public opinion. This work seems to participate in a larger project of cataloging, claiming, and perhaps even exoticizing both Rome and Egypt through architecture. Editor: Claiming? How so? Curator: Think about the role of the obelisk itself. It's an ancient Egyptian artifact, transplanted and recontextualized within the Roman cityscape. Goeree presents the Lateran obelisk as a central, defining feature, almost as if Rome is assimilating the power and history associated with ancient Egypt. It becomes a statement of dominance and continuity of empire. What’s your reading of the cherubs adorning the upper registers, seemingly displaying medallions? Editor: That’s true, it does suggest power through assimilation. As for the cherubs, the medallions make me think of propaganda almost…Like emblems to be displayed, broadcast even. Curator: Precisely! The imagery of the period often served to legitimize existing power structures, and artists worked within those frameworks. The choice to pair the meticulously rendered cityscape with what appears to be a more imaginative or perhaps even inaccurate vision of an "Egyptian Site" only highlights this dynamic, don't you think? How do you feel the location of this work within the Met impacts our understanding of it? Editor: Knowing it’s housed in the Met adds another layer – another claim through collection. Seeing it in a museum, far removed from its original context, reinforces its status as an object of historical and artistic significance, even a symbol of cultural capital. I hadn’t thought of it that way. Curator: These layers of history are embedded within the artwork itself and its reception. By acknowledging them, we get a richer, more nuanced understanding of its place in the world, and its complex historical echoes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.