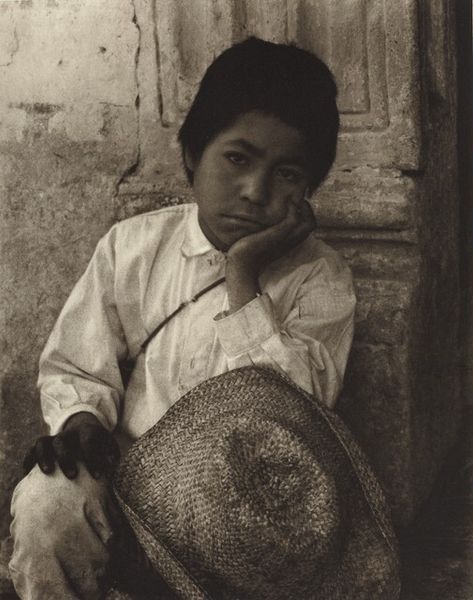

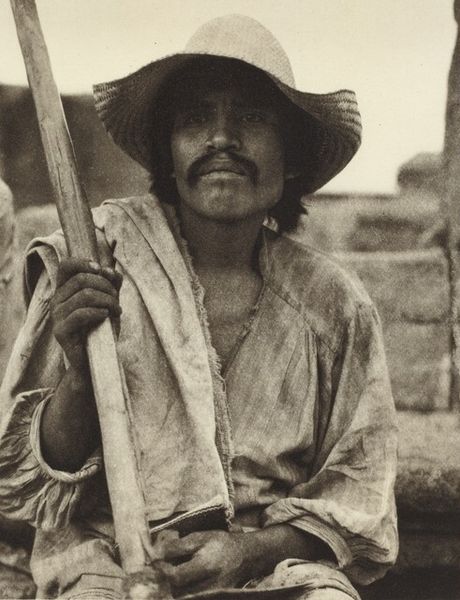

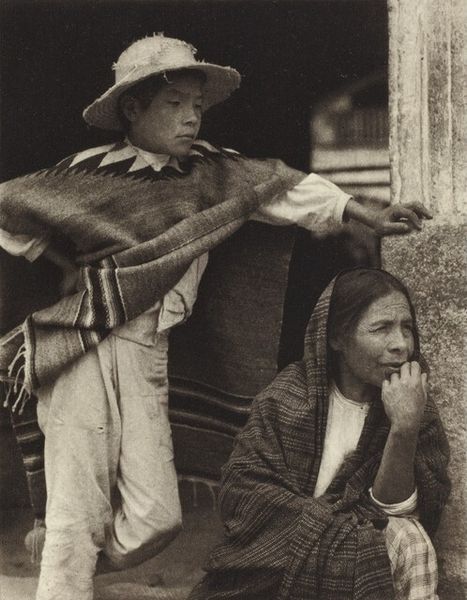

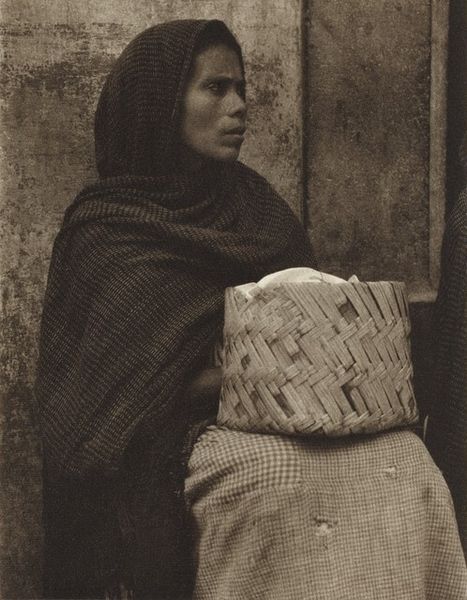

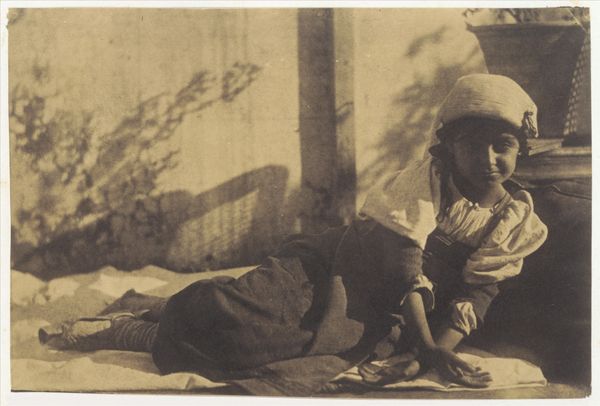

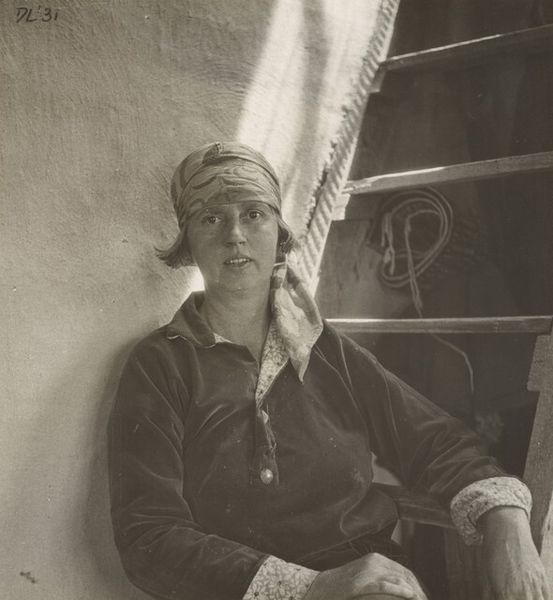

print, photography

#

portrait

#

portrait image

# print

#

black and white format

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

portrait reference

#

front view

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 16 x 12.4 cm (6 5/16 x 4 7/8 in.) sheet: 40.3 x 31.4 cm (15 7/8 x 12 3/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

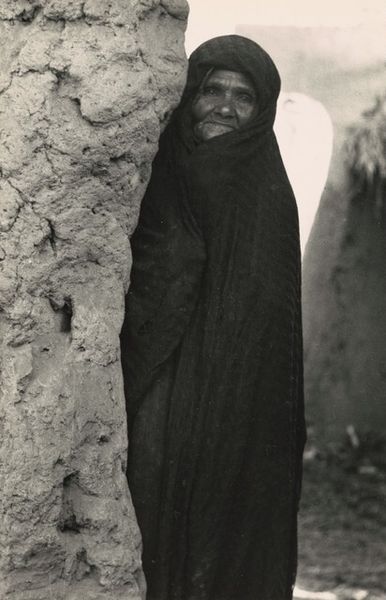

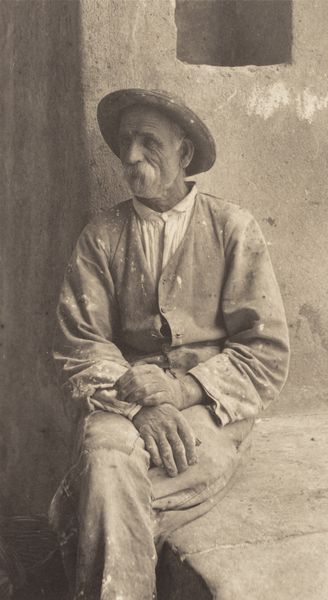

Curator: Paul Strand’s gelatin silver print, “Boy, Hidalgo,” tentatively dated between 1933 and 1967, arrests my attention. What's your initial impression? Editor: A certain stillness. The boy's gaze is direct, yet there’s a quiet melancholy in his eyes. The straw hat casts shadows, creating a strong contrast with the rough wall behind him, highlighting textures. There's an intimacy here, but also a distance. Curator: Indeed. Strand, after moving away from straight photography in New York, spent time in Mexico in the 30’s and that’s the historical context for this portrait, which becomes clear once we start understanding who is holding the power and creating these images. Consider how photography as a medium can serve various, often conflicting, purposes – capturing authenticity and creating romanticized images. Editor: It feels important to consider the boy’s own agency here, his identity is tied to Mexican history, revolution, and indigeneity. Was he complicit in how Strand was presenting him? Curator: That’s a fundamental question. Strand's work, like much documentary photography from the period, walks a tightrope between bearing witness and potentially exploiting its subjects. In those days photography in Mexico and Latin America was thought as modern and with its own revolutionary drive. The subject’s socioeconomic reality, for example, often remained unspoken and erased from narratives around the print. Editor: Absolutely, because his youth intersects with class and race. A single photograph might stand in for an entire population, reinforcing existing stereotypes or even creating new ones through romanticising an entire indigenous population in post-revolutionary Mexico. It demands a more layered interpretation. We can understand Strand as this avant-garde figure but not forgive his colonial gaze. Curator: By exhibiting these images in gallery and museum contexts, we encourage a necessary re-evaluation of Strand's visual language through contemporary lens. Editor: Exactly. Approaching works such as these armed with historical and intersectional perspectives allows us to challenge and broaden existing art narratives and imagine possibilities for engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.