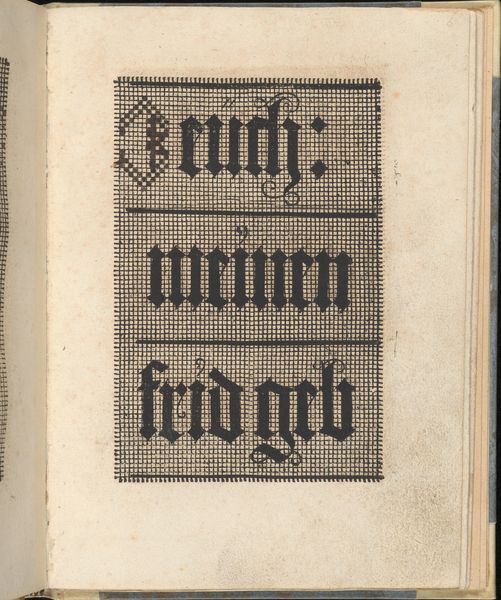

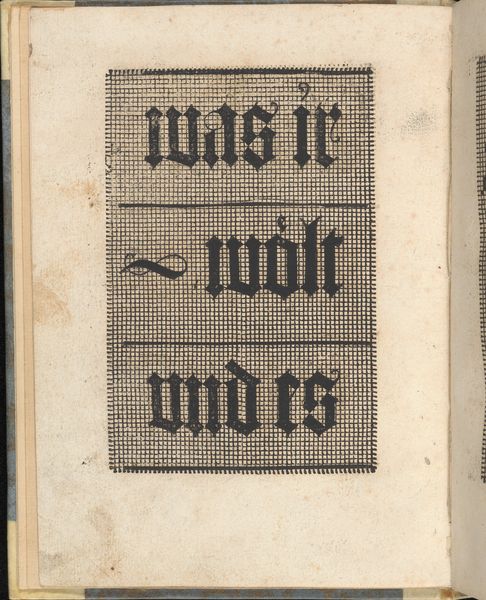

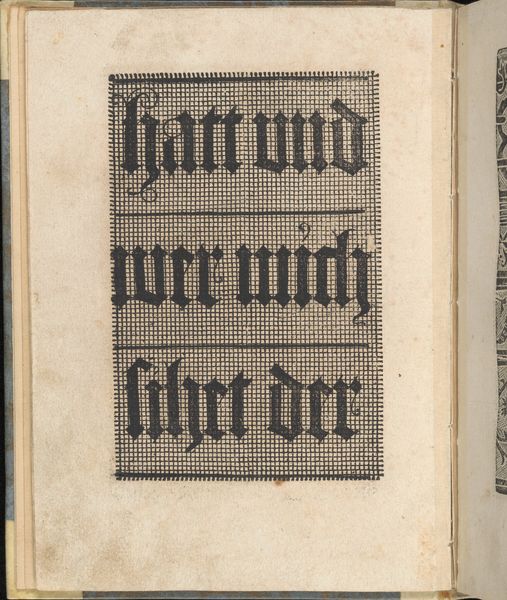

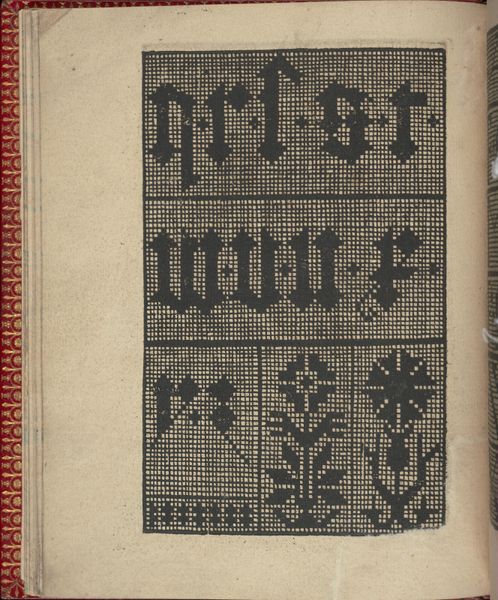

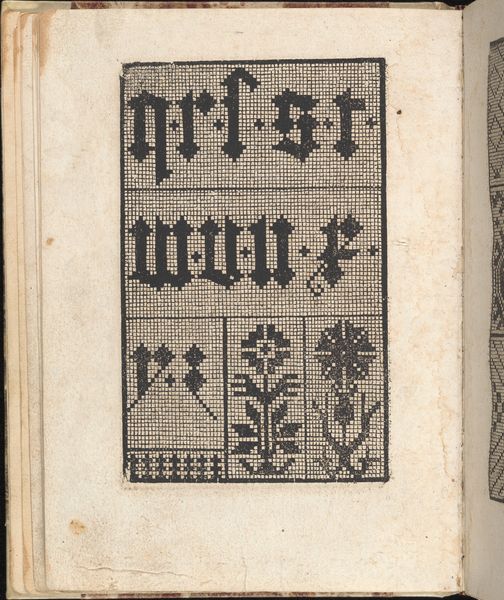

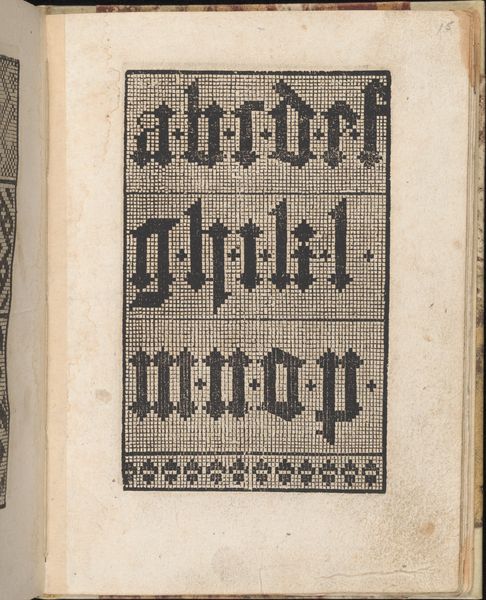

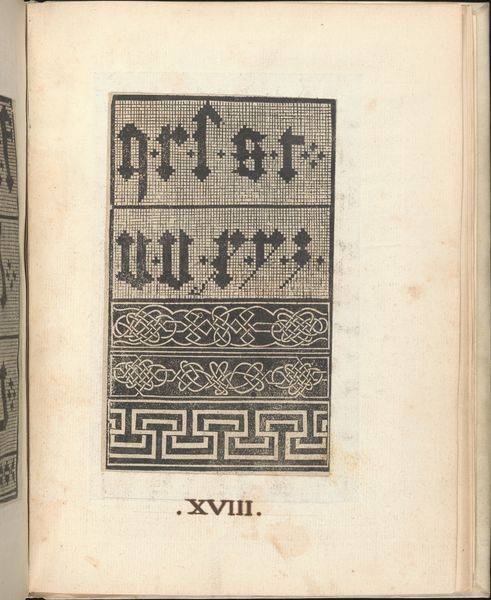

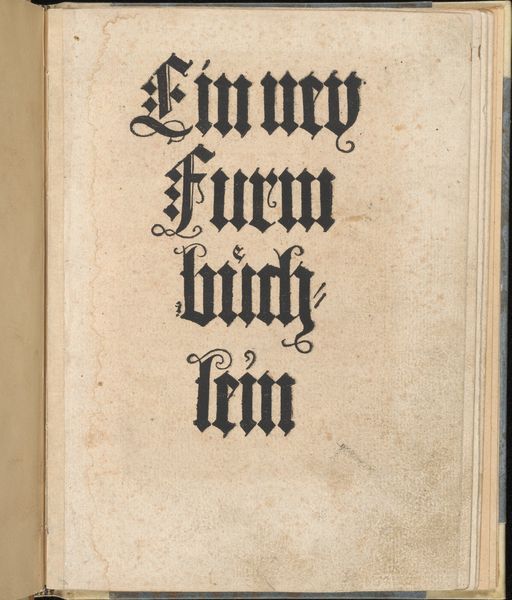

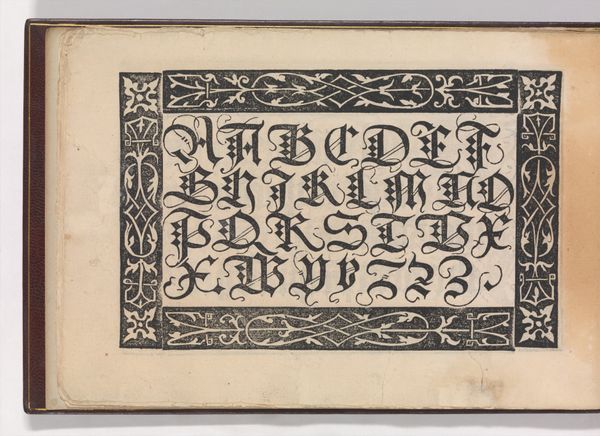

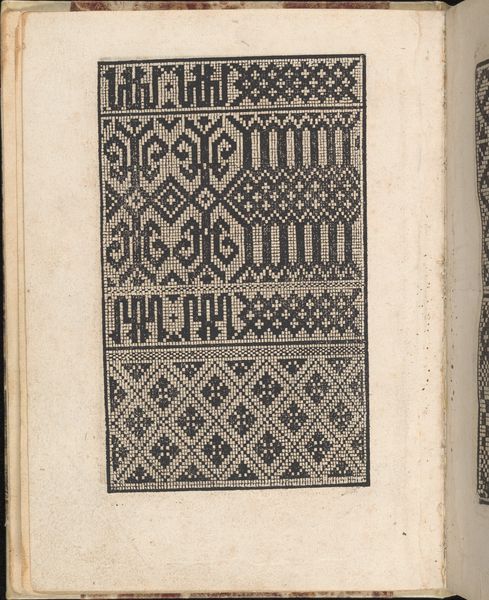

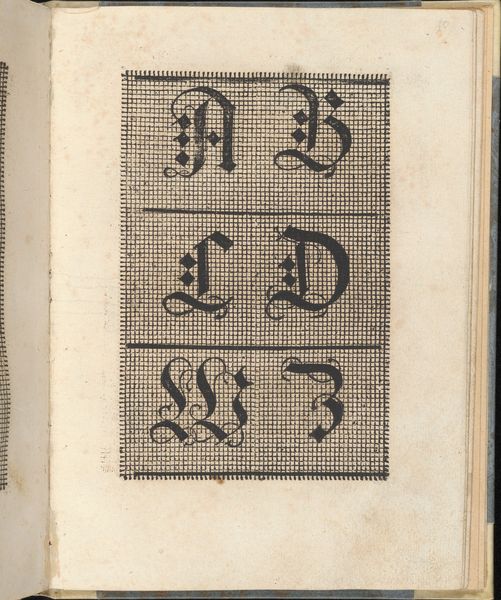

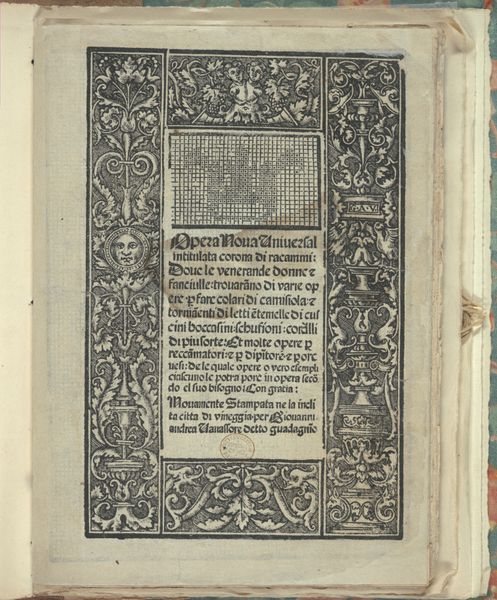

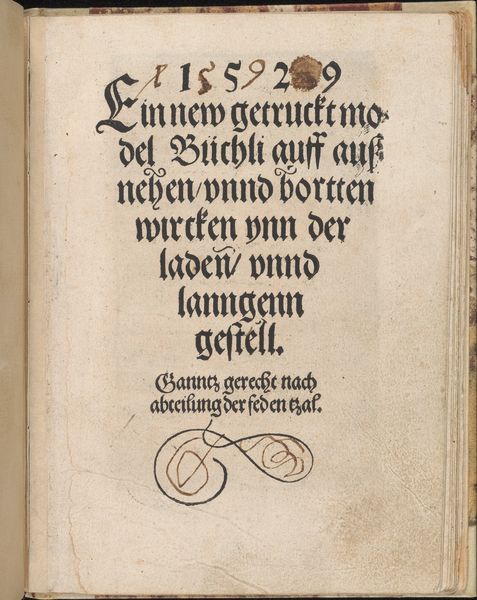

Ein ney Furmbüchlein, Page 7, recto 1520 - 1530

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, typography

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

book

#

typography

#

historical font

Dimensions: 7 7/8 x 6 1/8 in. (20 x 15.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have "Ein ney Furmbüchlein, Page 7, recto," a print made between 1520 and 1530 by Johann Schönsperger the Younger. It’s typography on paper. The texture looks very precise and ordered... what strikes you about this work? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the historical context of typography itself as a form of revolutionary mass communication. Here, though, we see it used within the framework of a book—presumably, a highly controlled and exclusive context during its time. This begs the question, what knowledge was being disseminated, and who had access to it? Consider the relationship between power, literacy, and the printed word during the Reformation. How might the "historical font," as the metadata suggests, reinforce or subvert existing social hierarchies? Editor: That's fascinating! So, looking at it as more than just design but as a vehicle for societal change... Is it possible to read a political message even without understanding the specific text? Curator: Absolutely. The very act of printing and distributing texts in the vernacular languages was often a direct challenge to the authority of the Church, which favored Latin. Even the stylistic choices, the deliberate design of this particular font, contribute to the overall message. We must remember printing allowed for reproducibility of the printing as propaganda or activism. Editor: So the act of printing itself becomes part of the narrative! That really makes me reconsider the power dynamics embedded in even seemingly simple things, like font choices and access to printing presses. Curator: Exactly. By examining typography within this socio-political framework, we uncover layers of meaning beyond the literal text, revealing the artwork's potential role in shaping discourse and challenging norms of its time. Editor: This reframes how I understand early printmaking – not just the image itself, but the cultural power behind it. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.