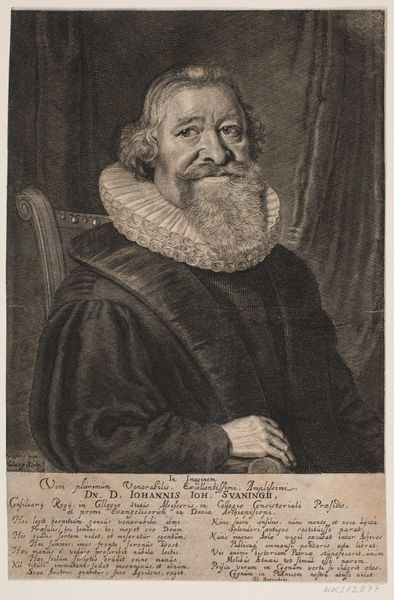

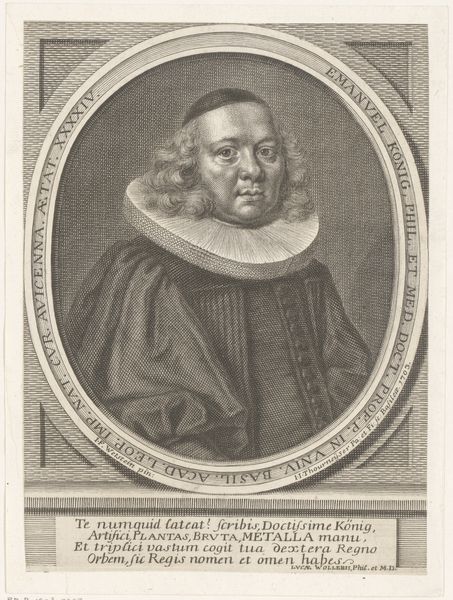

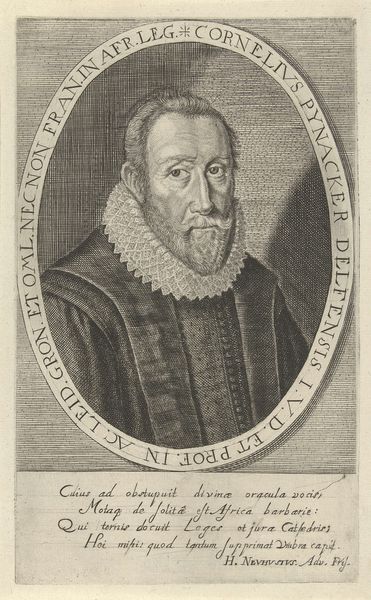

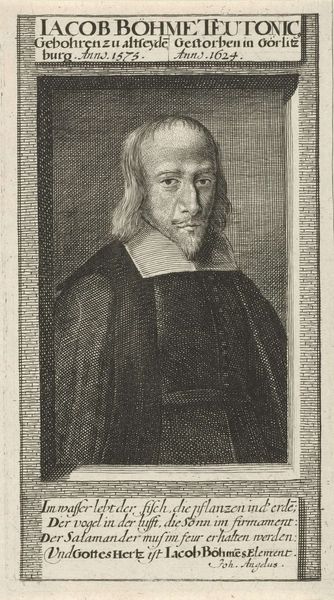

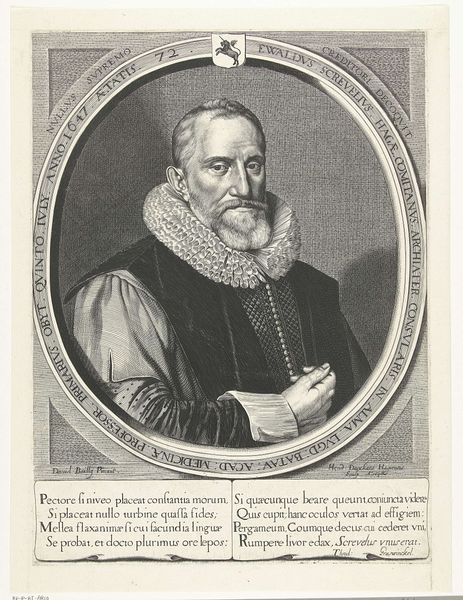

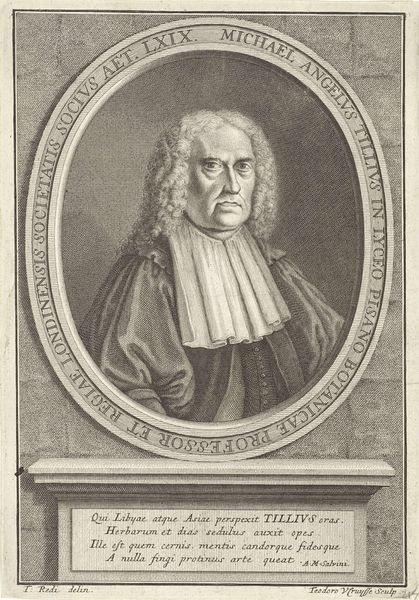

Portret van Johan Rippertsz. van Groenendijck op 69-jarige leeftijd 1649 - 1665

0:00

0:00

cornelisvandaleni

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 322 mm, width 223 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this engraving here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s a portrait titled "Portret van Johan Rippertsz. van Groenendijck op 69-jarige leeftijd", made by Cornelis van Dalen I sometime between 1649 and 1665. Editor: My immediate impression is of gravitas. The weight of years and perhaps societal expectations seem etched into every line of his face. There's a certain weariness around the eyes, despite what seems like a stoic expression. Curator: Indeed. The print is a detailed representation of Johan Rippertsz, who was burgomaster – or mayor – of Leiden, multiple times. Notice the stark, unwavering gaze; his features are deliberately accentuated to portray wisdom and authority. Editor: The symbols are evident, but I can't help thinking about who this man truly was. The Dutch Golden Age portraits, like this, frequently show only the elite, overlooking the plight and efforts of ordinary people, whom figures like Rippertsz impacted directly. Was his authority beneficial or restrictive to Leiden’s broader population? Curator: An important consideration. Beyond a mere record of likeness, we can interpret Rippertsz's attire, particularly the scholarly cap and the formal collar, as symbols of his standing. These details subtly affirm the era's societal hierarchy. The engraving itself is quite masterful, capturing texture through densely etched lines. Editor: I agree about the engraving; it’s exquisitely done, especially when you consider how it elevates his presence, making him appear almost unapproachable. It underscores the constructed nature of power. These portraits served to solidify social hierarchies, embedding a system of respect and obligation in visual culture. Curator: Yet we see this genre of formal portraiture enduring precisely because of that interplay between personal identity and social expectation. An engraving such as this had power—literally creating, reifying, and propagating the image of those in authority. Editor: Absolutely. This portrait not only reflects its time, but also speaks volumes about how societies consciously construct and uphold narratives of power and privilege. How those in positions of leadership are presented matters, because it impacts not just perception but policy. Curator: Precisely. These images were designed to project qualities considered virtuous and worthy of emulation in leadership, to remind everyone, including the sitter himself, about his duties and social status. Editor: Thank you. Thinking about images like this in our time can help us question the images of leaders that we create and disseminate now, as well. Rippertsz here could provide a point of contemplation, about representation, justice, and memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.