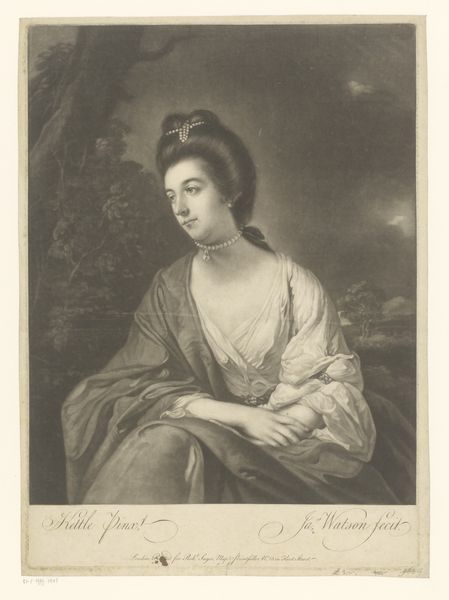

engraving

#

portrait

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 326 mm, width 226 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a print from 1756, a portrait of Elizabeth Montagu by James McArdell, described as an engraving. I'm struck by the formality and stillness, almost as if she’s presented as a commodity. How do you see this work? Curator: This engraving, while seemingly a simple portrait, is rich with information about 18th-century society and its means of production. Think about the labour involved: the artist, the engraver reproducing Reynolds' original painting. This piece is, in effect, a product manufactured and disseminated for consumption, almost like celebrity merchandise. Consider how the layers of labor—from painting to engraving to printing—affect our perception of Lady Elizabeth. Editor: So, it's less about her individuality and more about the process of making and distributing her image? Is the material of the engraving part of its meaning? Curator: Absolutely. The engraving medium itself implies replication and broader accessibility. This was not a unique oil painting only viewable by a select few. Instead, it became a commodity for a burgeoning middle class. Editor: It's fascinating to think of it in those terms. Curator: How might the materials involved in its production -- paper, ink, and the tools used by the engraver - have impacted both the aesthetic and the availability of this image? Editor: I guess, making it an interesting social document, not just a pretty picture. Curator: Precisely. The materials, labor, and intended market are inextricably linked. These choices offer important clues about its intended function within society. We understand it differently now. Editor: This makes me look at it in a whole new light. Curator: I agree. The lens of materiality reveals the profound connections between artistic production, social structure, and economic forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.