Dimensions: image: 46.36 × 36.51 cm (18 1/4 × 14 3/8 in.) sheet: 50.8 × 40.64 cm (20 × 16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

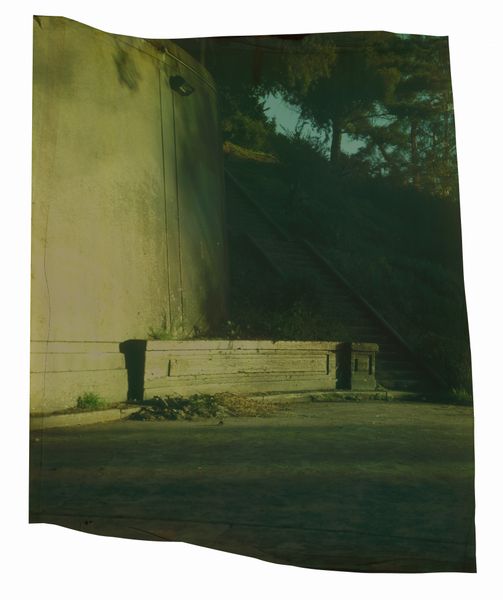

Editor: So, here we have a photograph by Kris Graves, taken in 2020, documenting the Matthew Fontaine Maury Plinth in Richmond, Virginia. It’s… stark, seeing the graffiti so prominently displayed on what I assume was once a pristine monument. What strikes you first about this image? Curator: I notice how the image lays bare the changing relationship between the monument, the materials of which it’s made, and the society it inhabits. The original monument was about control - Maury’s control of the seas, the Confederacy’s control of enslaved people. Now, the materials themselves—stone and paint—testify to a loss of that control. Editor: How so? It looks pretty controlled; doesn't public art often involve permissions? Curator: But this *isn't* authorized, is it? See how the graffiti challenges the very fabric of power relations embedded in the monument's creation and original purpose? Consider the cost of materials, the labor, both then and now: the carving of stone to erect the monument and the spray paint applied as protest. These are acts of making and unmaking. Editor: So, you are saying that materials hold a cultural message beyond being simply stuff? How the materials are handled, and by whom, shapes their message as much as the end form? Curator: Precisely. The act of defacing the monument becomes a counter-narrative, a raw assertion of power by those historically marginalized. The materials now tell a different story. The tags indicate that materials are used to communicate messages of resistance against oppressive forces and rewrite historical narratives on the plinth itself. The plinth itself becomes the public art, it seems to have found a second voice now, through this repurposing. Editor: I see, so the picture is about more than just the art, but the physical presence and manipulation of matter? Curator: Exactly! The photograph doesn’t just capture a defaced monument; it freezes a moment of social and material transformation. What we’re left with is a poignant examination of how meaning is constructed, contested, and ultimately, embodied in the objects around us. Editor: Fascinating! Thanks for broadening my perspective and offering a fresh interpretation. Curator: My pleasure. The real understanding is born of looking and feeling, and of listening to one another's insights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.