Copyright: Public domain

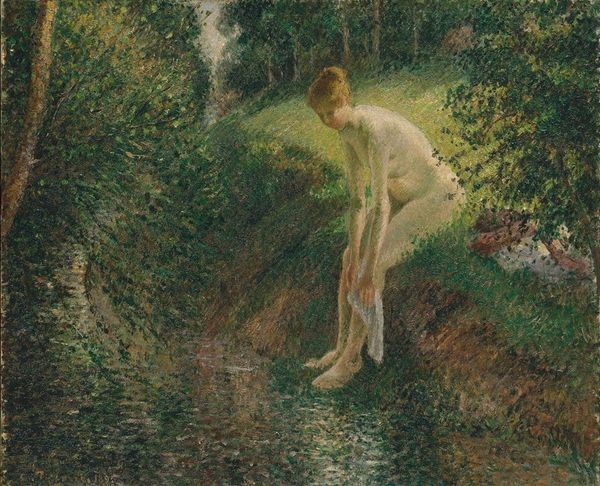

Curator: Oh, what a somber, yet beautifully composed scene. The lady, still, pale... adrift. Editor: We're looking at "The Lady of Shalott", an oil painting crafted by Walter Crane in 1862, currently housed at the Yale Center For British Art. This work exemplifies the Pre-Raphaelite movement’s fascination with Arthurian legend and its exploration of feminine identity, a pivotal concept in Victorian England. Curator: Absolutely, you immediately sense the entrapment, the consequence of defying social norms. Her journey in the boat—is it a suicide or escape? I am also drawn to Crane's commitment to Romantic landscape—"mother nature heavy" feels pretty on the nose here as if the lady and nature exist as a unit in distress. Editor: Indeed. This painting emerges amidst a backdrop of increasing industrialization and social change. The Pre-Raphaelites sought to return to the perceived purity and artistic values of the pre-Renaissance period, but I question their social narratives, because paintings such as these did not come about by accident. "The Lady of Shalott", both the legend and this painting, present the woman trapped in her interiority because of patriarchal restraints on visibility. It’s not so different now! Curator: And the visual symbolism reinforces this idea. The natural environment both imprisons and cradles her, reflecting how restrictive social expectations and constraints have, even today, become tragically internal. It’s also intriguing how the composition stages the painting. Notice how dark and muddy it appears around the edges: death is approaching and engulfing her! Editor: Crane uses color and light to enhance this feeling. The subtle yet vibrant details draw our attention and then forces us to confront themes like artistic confinement and tragic romanticism, themes very important to the cultural dialogue of Crane’s time, the repercussions of which continue even now. But also look to our current social circumstances. Can we draw parallels to today’s celebrity or influencer culture, in which freedom comes only through utter isolation, even symbolic or actual death? Curator: It's that sort of conversation, linking historical contexts to current predicaments, that makes art so powerfully and profoundly timeless. Editor: Precisely, it's in reflecting upon these interconnected legacies that we derive meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.