painting

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

painting

#

romanticism

#

academic-art

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

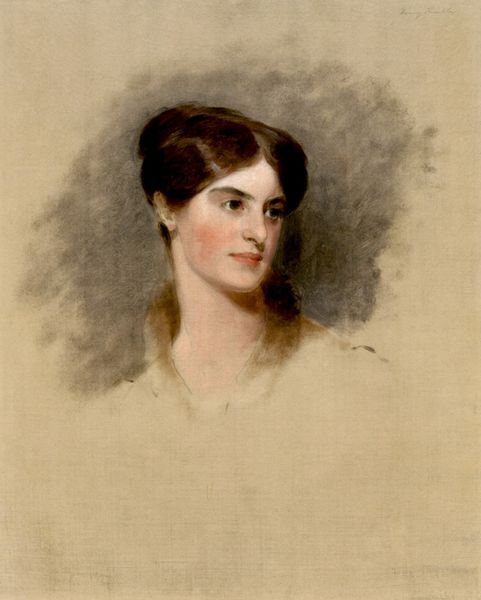

Curator: Before us, we see Gilbert Stuart's "Portrait of a Lady," dating from around 1820 to 1825. It's a striking, yet seemingly simple, figurative work. Editor: There's an arresting serenity about her. The soft, almost hazy brushstrokes and subdued palette give her a gentle presence. She seems almost to be emerging from a mist. Curator: Stuart was a master of portraiture during his time. This painting is an example of the impact that romanticism had in artistic productions of the period, and the expectations placed on representations of the subject at that time. Her calm demeanor reflects a kind of social ideal that Stuart captured so effectively. Editor: Absolutely. The details – or rather, the carefully *implied* details - of her clothing suggest a social position. The hint of a frilled collar is all we need to infer elegance and status, which acts as an important symbolic component. Her soft facial features also project purity. It almost feels as if Stuart tried to portray her inner beauty above everything else. Curator: This resonates with broader historical contexts. During this era, portraits served less as mere representations and more as constructions of social standing and aspiration. Artists were actively shaping the way sitters wished to be seen by posterity, projecting a family’s standing and ideals, in painting and in life. Editor: Yes, precisely. It is not necessarily *who* she was, but *what* she represents as part of that historical period: virtue, restraint, perhaps a carefully cultivated image of domesticity and grace that women of this period aspired to represent. I wonder what emotional complexities, or psychological components, could lie beneath the facade she represents to society? Curator: It's that interplay between social performance and the interior life that I find endlessly fascinating. This work demonstrates how artists, patrons, and societal norms all collaborated to craft visual narratives, defining femininity for consumption, perhaps setting up for great dissention of views within the next few decades. Editor: Agreed. It prompts us to consider not only who this woman was but what she meant, and the broader cultural values and psychological projections inherent in portraiture from the Romantic era. Curator: Precisely, and how societal norms directly effect even the smallest portrait! Editor: A moment caught, yes. And how fascinating those moments are, still able to elicit thought in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.