print, engraving

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

line

#

cityscape

#

tonal art

#

engraving

#

building

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 365 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

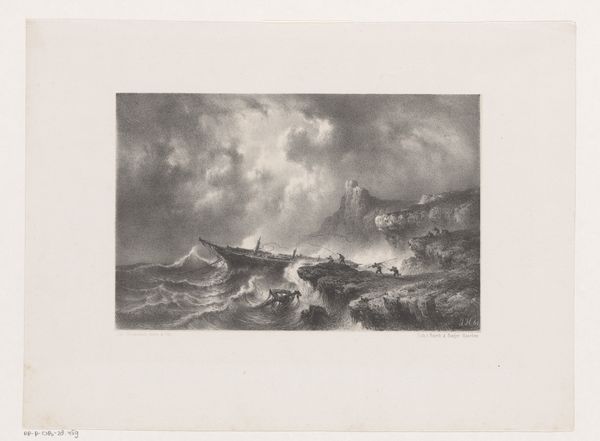

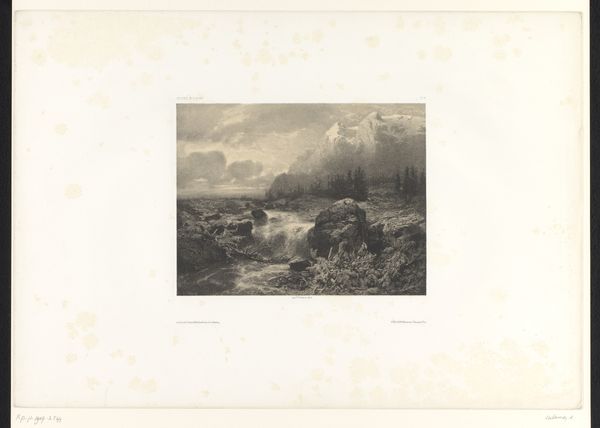

Curator: Gudin's "Huis aan de kust bij maanlicht," or "House by the sea by moonlight" from 1824. This engraving, done with ink on paper, strikes me as incredibly somber. What’s your initial read? Editor: There is a romantic desolation, certainly, but I also feel the power of nature reflected. I can almost feel the dampness in the air and smell the brine. I immediately think about access and protection. Who inhabits such a precarious home, and what historical circumstances position them there by the sea? Curator: That proximity to the elements is so potent, especially considering this is an engraving, which necessitates a very different kind of labor than painting. You know, there’s such a laborious craft involved. This isn't a spontaneous expression, but a deliberate carving, printing and transferring an image. How might that deliberate creation impact our viewing of it? Editor: The printmaking process emphasizes how landscapes such as these, during Romanticism, served as reflections of internal states and political turmoil, even sites of resistance. Consider the implications of widely distributed printed images democratizing artistic experience. The question is, who has access to these representations, and what narratives do they perpetuate or challenge? Curator: That ties into the idea of access in general. Printmaking opened up a visual landscape to a broader audience, and that meant considering materials in different ways. Cheaper, reproducible materials create accessibility, yet we are also concerned about the original, the hand of the artist, right? Editor: Yes, and it speaks to broader power structures. How is land and resources allocated? Who has the privilege to dwell securely away from the encroaching sea versus being forced to build their homes on its edge? The solitary figure adds to this reading, dwarfed by the ocean. Curator: Gudin presents a world of stark beauty made through a highly structured medium. Considering the labor and materiality involved forces us to question our expectations for what constitutes "art" and for whom it is created. Editor: Ultimately, the print acts as a conversation starter about humanity’s place within an often unforgiving world, especially pertinent to considerations about inequality. A testament to how art serves not only as aesthetic expression but as an active player within a broader social landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.