photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

cityscape

#

realism

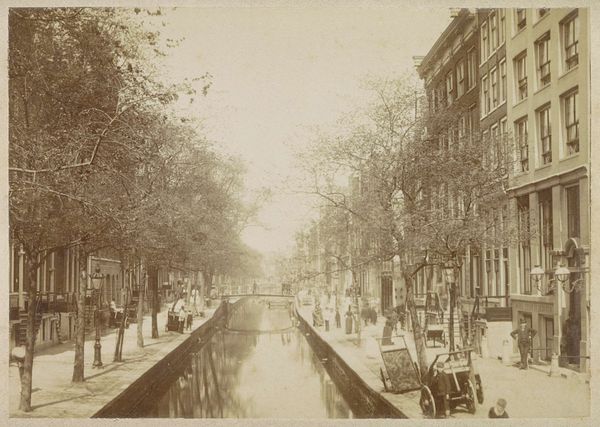

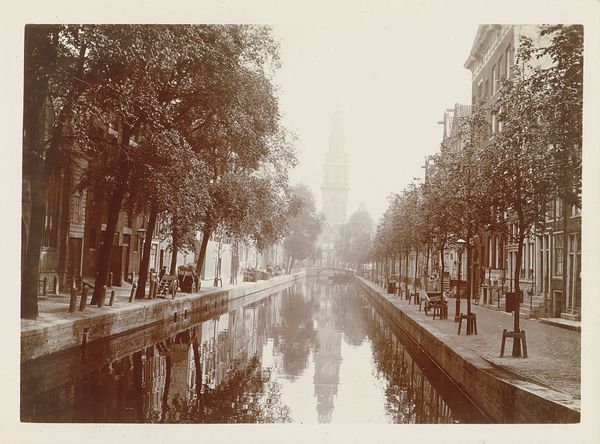

Dimensions: height 50 mm, width 80 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

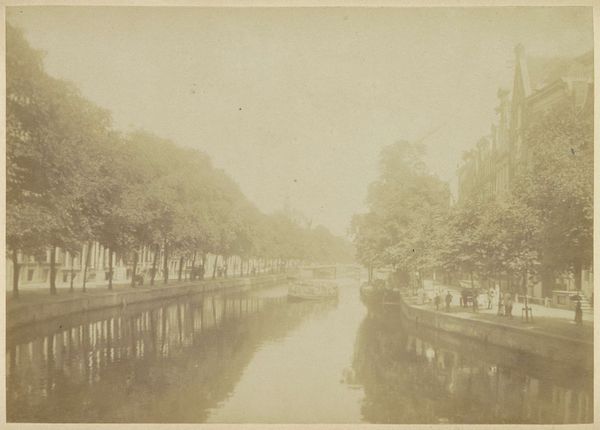

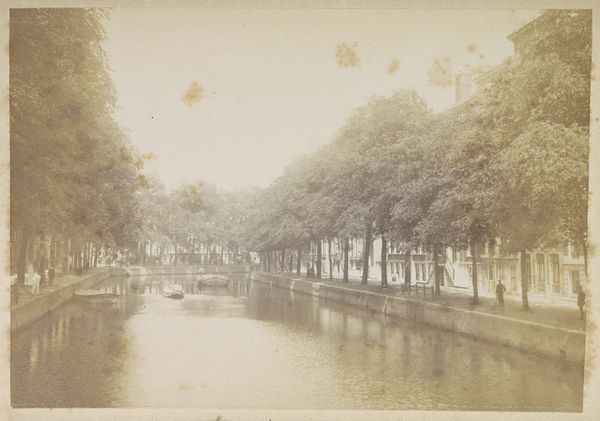

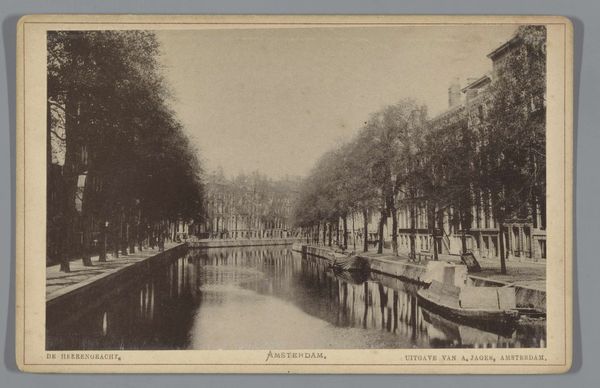

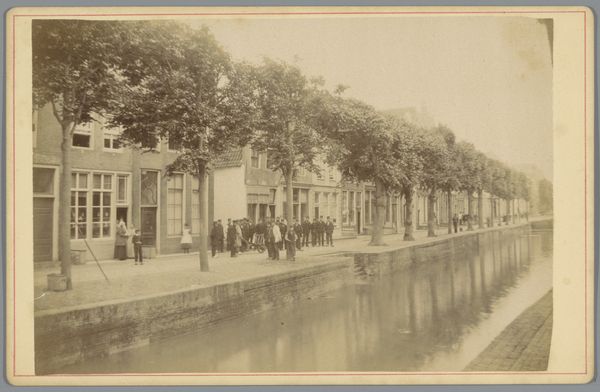

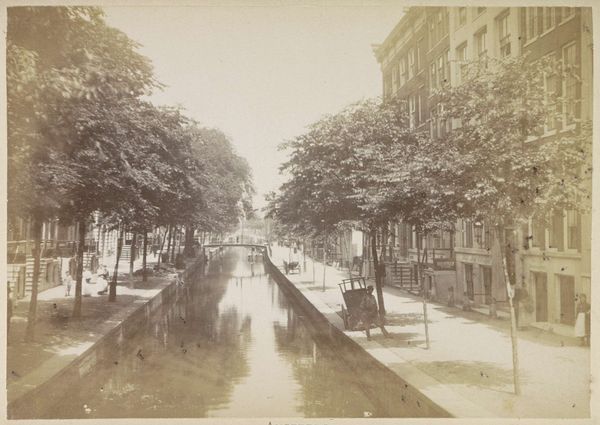

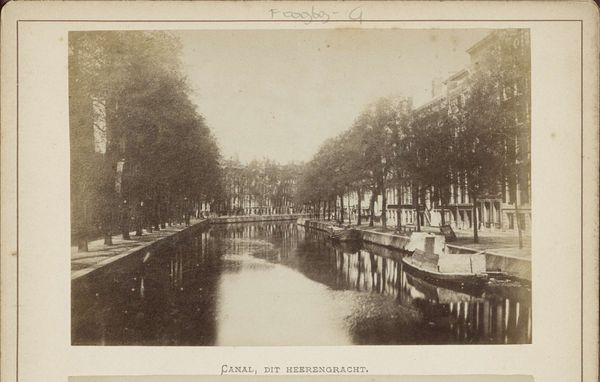

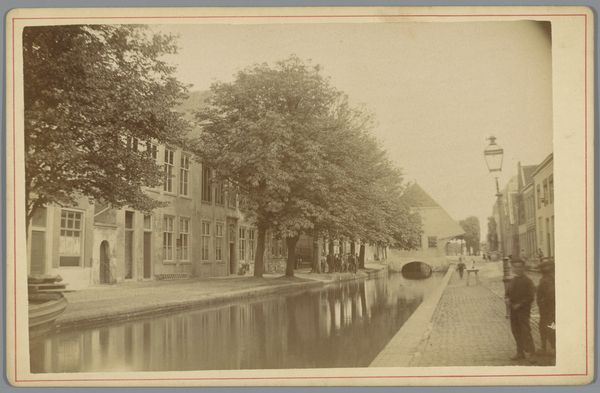

Editor: Here we have "Gezicht op de Herengracht te Amsterdam," a gelatin-silver print, dating from around 1860 to 1900. It’s a very calming image; the symmetry is quite striking. What elements stand out to you? Curator: The dominant aspect for me lies in its formal organization. Observe the parallelism, how the artist meticulously frames the canal with rows of trees. This directs the eye linearly towards the blurred architecture in the background. Editor: So the artist is using lines to create depth? Curator: Precisely. Notice, too, the tonal range, the subtle gradations of light and shadow achieved through the gelatin-silver process. The reflections in the water are not merely representational but serve to duplicate and abstract the forms above, creating a layered visual experience. It moves the eye beyond a simple surface reading. Editor: I see what you mean; it’s not just a picture of a canal. How do you think the limitations of early photography might have affected its composition? Curator: An astute observation. Given the slower exposure times, the stillness is not just aesthetic; it’s born from necessity. Any movement would blur. The emphasis, therefore, falls on static architectural and natural elements, arranged in a way that maximizes visual stability. The artist works within constraints to highlight stillness. Editor: So, form and technique become intertwined… I’m starting to look at photography in a new way now! Curator: Indeed. It reminds us to attend closely to the interplay between materials, methods, and visual outcomes. A constant, close reading brings depth. Editor: I definitely agree. Paying attention to formal elements reveals how the artist achieved a specific aesthetic despite technological challenges of the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.