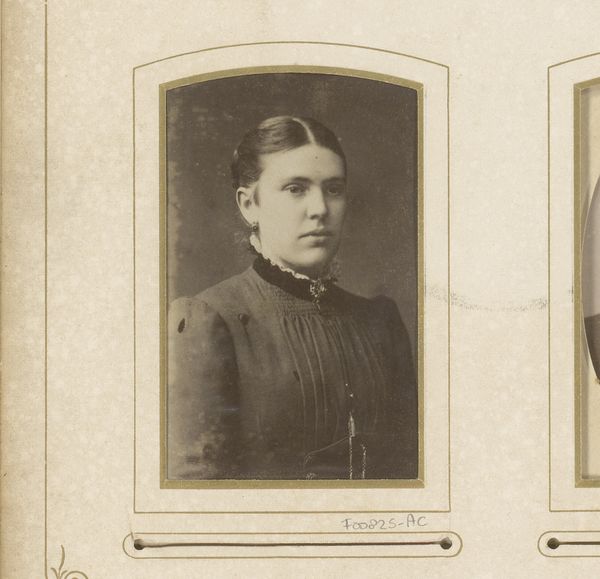

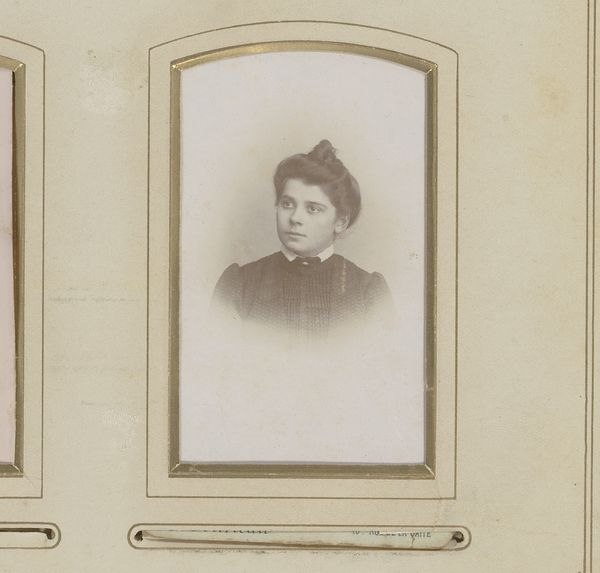

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this, I feel a profound sense of constraint and a subtle defiance, all captured in the subject's gaze. Editor: This is a gelatin-silver print, a photograph taken sometime between 1865 and 1895, attributed to Thomas Martin Staas. It's titled “Portret van een jonge vrouw”—Portrait of a Young Woman. The composition is fairly typical for the period. Curator: It's more than typical; it’s representative of the stifling societal expectations placed on women during this era. Her attire, her composed expression, they speak volumes about the performance of femininity and the limitations imposed by patriarchal structures. Do you see a lack of agency in this pose? Editor: I see both limitation and access. Portraiture democratized visibility. Middle class members would utilize photography in ways that previously would have only been afforded to the wealthy, specifically with painted portraiture. There is something intrinsically humanizing about her direct, even, gaze, however sober. Curator: But is she really seen, or is she performing the expected image of docile womanhood? Photography in the 19th century often reinforced power dynamics and class structures, manipulating the idea of gender through posture. Does that buttoned up top allow her a real position of power? Or does it limit her. Editor: We're both projecting onto this historical image based on the access we now have to intersectional conversations that are very present now, in 2024. Curator: And that is entirely necessary. Looking at historical objects with contemporary theory provides meaningful insight. To deny an object’s capacity to lend itself to cultural relevance, historical relevance, is negligent. Do we truly value objects by taking them at face value, historically, rather than contextualizing it within present ideas? Editor: It presents more questions than it answers, to be certain. The power dynamics in photographic portraits are rarely simple, or immediately legible across a gap of almost two centuries. Thank you for the opportunity to examine it through new perspectives. Curator: Of course, thank you as well. These types of dialogue only work through both present context and historical framing. It's the necessary marriage to keep our conversations, and our objects, relevant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.