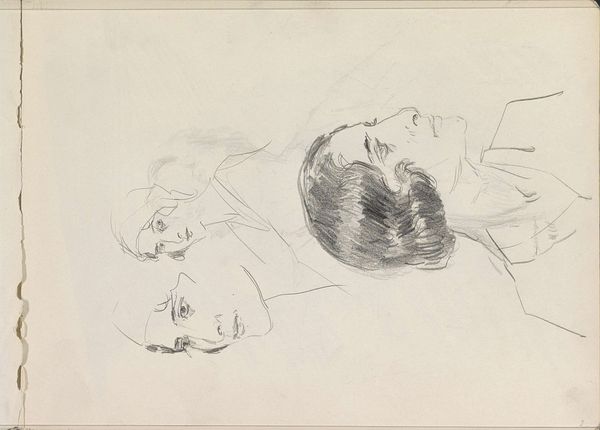

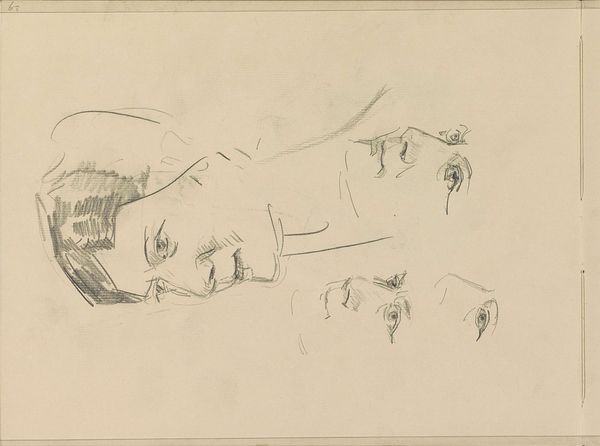

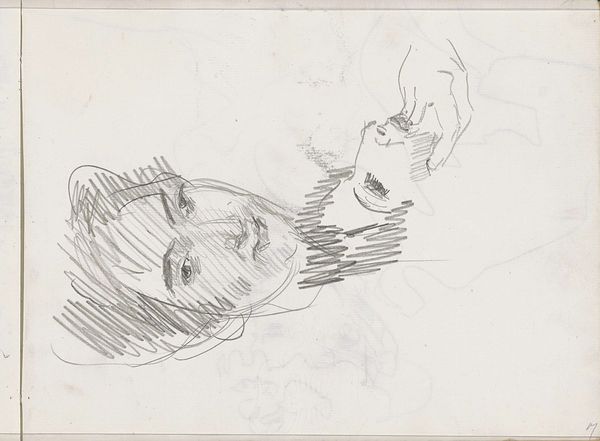

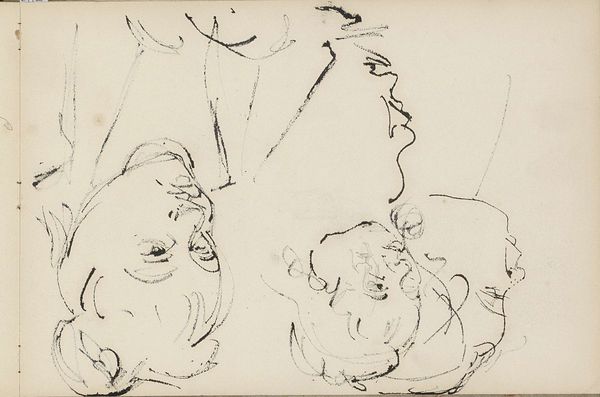

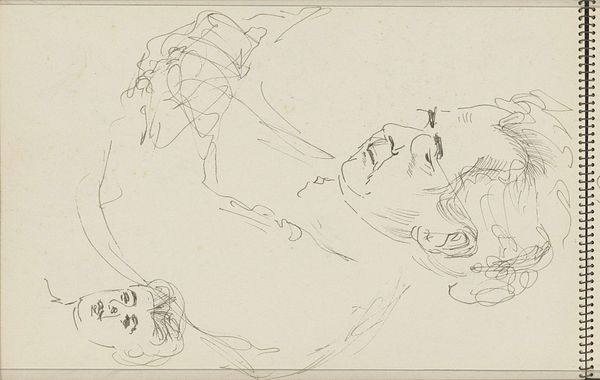

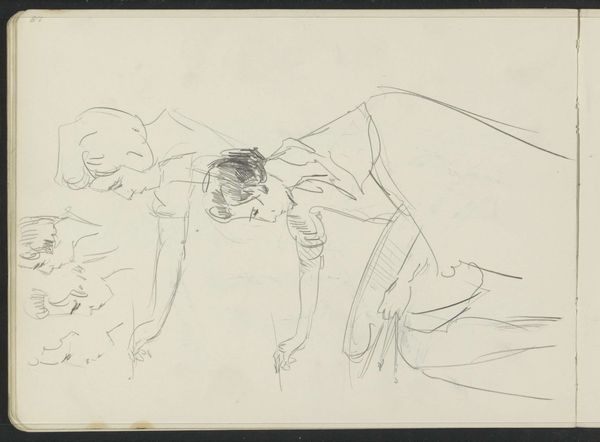

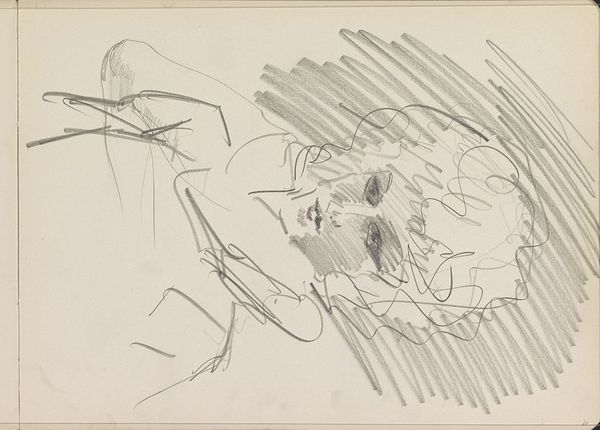

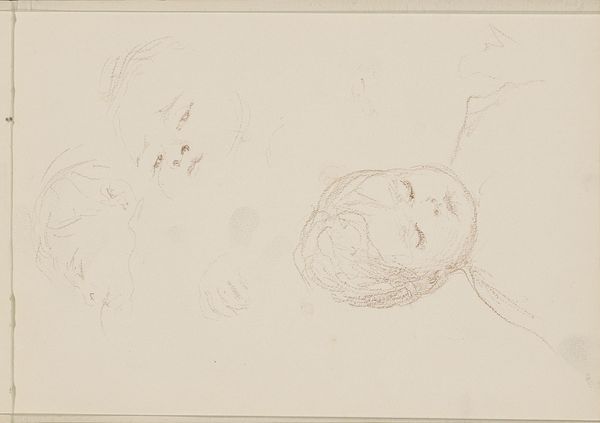

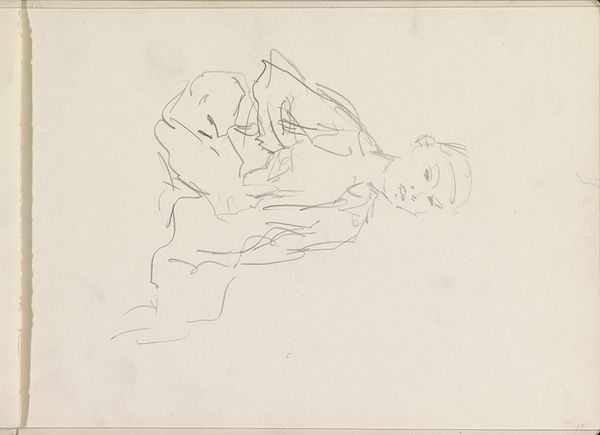

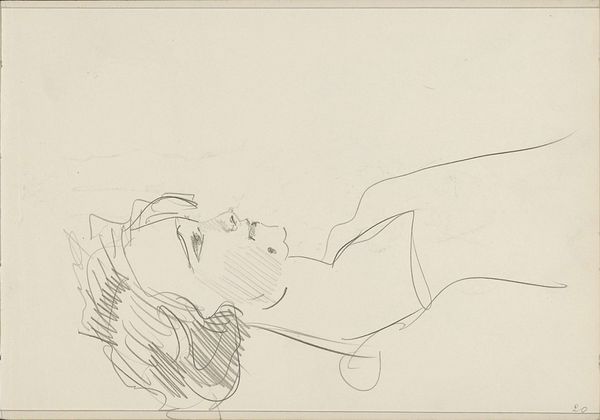

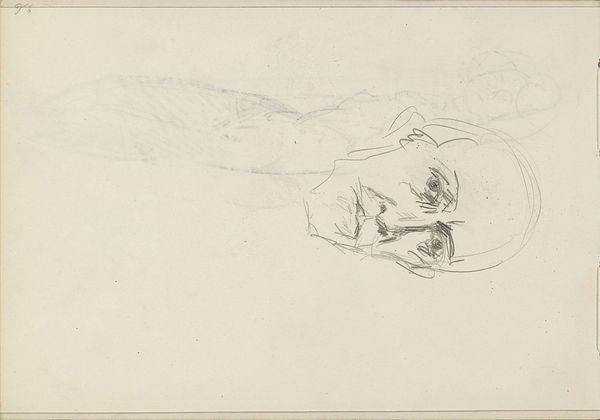

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We are looking at "Studieblad met gezichten", a pencil drawing by Isaac Israels, made sometime between 1875 and 1934. It's currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. What's your initial reaction to it? Editor: Spare. Vulnerable, even. The line work is so delicate, and the gaze of each face feels very exposed. I wonder, are these studies of real people, and what were their circumstances, or even Israels’ reasons for representing them this way? The turn of the head away from any active or demanding connection makes one question any intention other than being observed, watched, looked at as if to try to see them from within. Curator: Precisely. Israels came of age in a period of tremendous social change, and his work often reflected the shifting dynamics of class, gender, and identity in Dutch society. These faces, in their varied positions and states of repose, resist idealization. I read this not only as realism, but also as a reflection of the marginalized. Consider the upward tilt of their faces; are they seeking something, or being scrutinized by those in power? Editor: Intriguing to frame their gaze upward as being scrutinized rather than hoping. One may focus on the angle of each subject’s face. By emphasizing certain lines, Israels directs our eyes through the planes of each form, the artist guides us, creating emphasis. It’s about more than representation; it’s an exploration of form itself. Consider the economy of line—each stroke carries such weight and deliberateness. How do these stylistic elements, like this reductive approach, play into the subject, and those gazes? Curator: That formal distillation is key. By reducing each face to its essence, Israels forces us to confront their humanity directly, without the distraction of ornate detail. I also believe he's implicitly critiquing the conventions of academic portraiture. In whose interest are we meant to capture and embalm their representation, what is this tradition for if not an exaltation of societal expectations for ideal subjects? He gives us the raw immediacy of human presence, with each drawing like a mirror for contemporary audiences to look into how we, and the status quo, deal with those less well off than us. Editor: Perhaps. But the drawing also stands as a timeless investigation of proportion, light, and shadow—a study in the fundamentals of visual representation. The social context certainly adds layers, yet even without that, the artwork would have a power inherent in the beauty and sensitivity of line. It reminds me how essential line is to drawing. Curator: Perhaps we can find some common ground there!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.