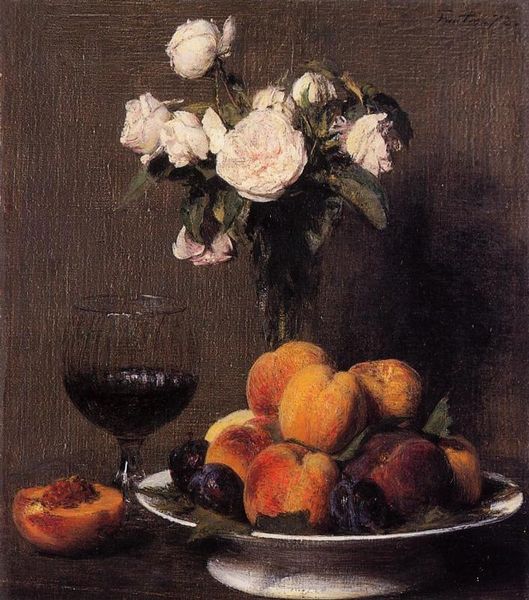

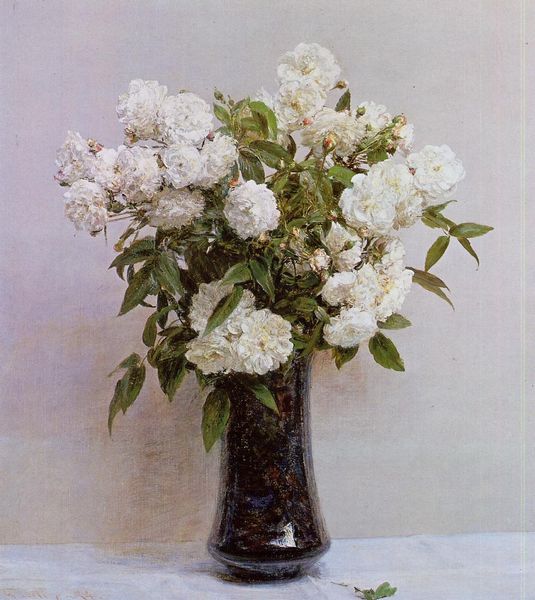

Copyright: Public domain

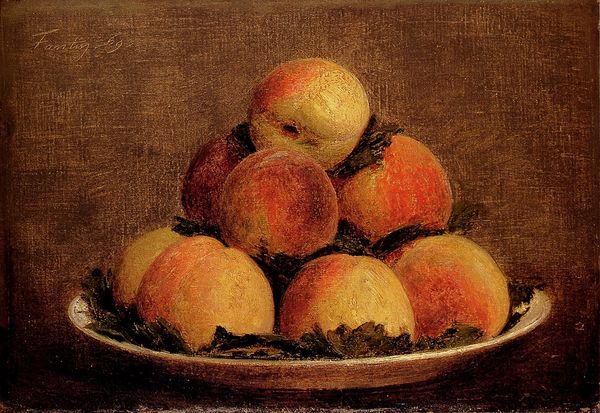

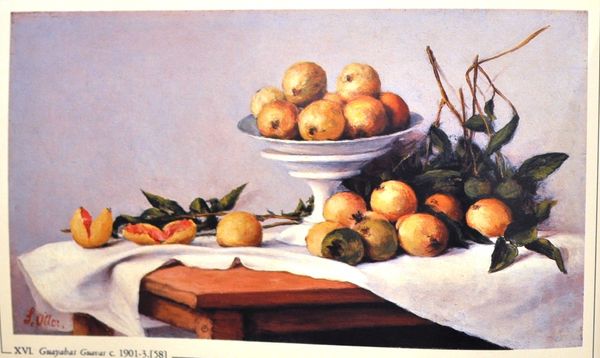

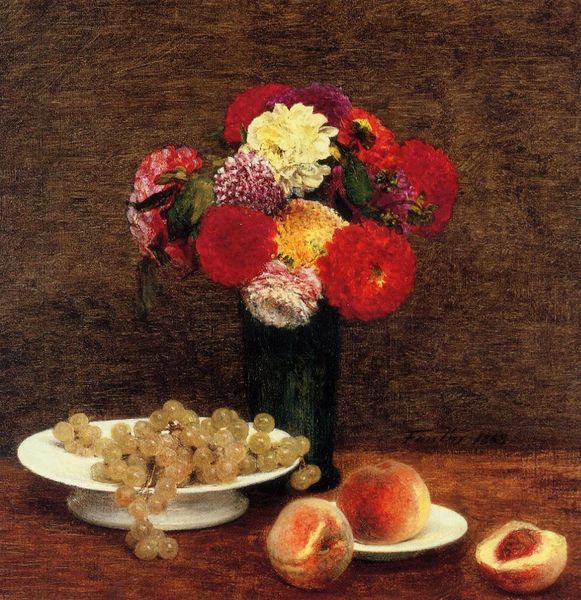

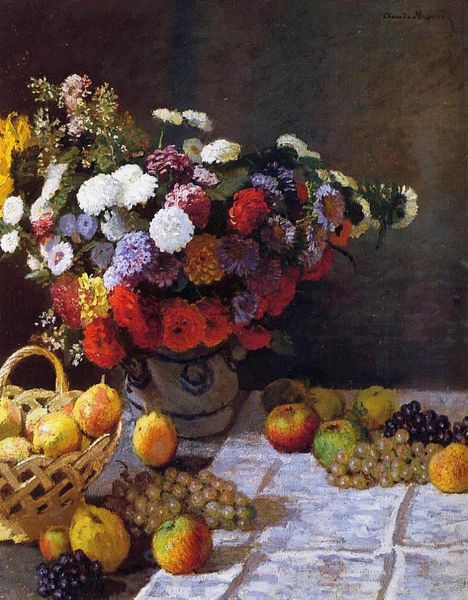

Curator: Henri Fantin-Latour’s “White Rockets and Fruit,” painted in 1869. It’s an oil on canvas still life. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It’s… strangely calming. There’s this subdued lighting, a kind of velvety darkness behind the bursts of white. It’s a classic composition, fruits and flowers arranged so delicately. Almost staged in its perfection. Curator: Fantin-Latour was working within a very specific tradition, deeply influenced by the Dutch Masters and a revived interest in realism in the mid-19th century. Consider the context – this is France, on the cusp of the Franco-Prussian War. His art existed within those looming socio-political forces. Editor: Right, and there’s an undeniable tension, isn’t there? A dissonance perhaps? I mean, you've got these opulent symbols of wealth, of nature’s bounty, displayed with such care, and at the same time a hint of the darkness of colonialism inherent in these exotic displays of material objects, especially the fruit from warmer, non-European, climes. Curator: I'd argue the scene lacks drama – this is not baroque, the forms, even with the shadow play, feel subdued. The brushwork is delicate; he meticulously renders the texture of the fruit, the porcelain bowl. It catered to bourgeois tastes that preferred comforting visuals. Editor: But doesn't the very act of carefully selecting and arranging these items, displaying them, speak to something beyond simple documentation? He is deliberately controlling our view, choosing what we see, in a way asserting dominance over nature itself and a visual embodiment of capitalism in action. Curator: He walked a line between artistic integrity and commercial appeal. His still lifes provided a measure of financial security, which freed him to paint other kinds of work that engaged his core principles. Fantin-Latour straddled that uncomfortable divide as much as Manet or Courbet, while working to advance their work and social standing. Editor: It’s this tension, that makes the work compelling, really. This inherent dissonance of the beautiful as commodity object. We need art to call our history to account for its moral failings. Curator: I am not so sure it is always up to artists to do so explicitly. These subtleties often contain a range of meanings for us to ponder. Editor: Exactly, these still lifes offer much more than an exercise in mimicry. They're about our place in that chain of seeing, being seen, consuming, and forgetting. Curator: It provides an intriguing commentary of the quietude present at a pivotal moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.