painting, watercolor, ink

#

water colours

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

japan

#

figuration

#

handmade artwork painting

#

watercolor

#

ink

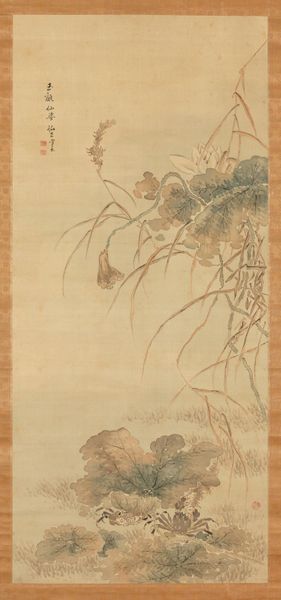

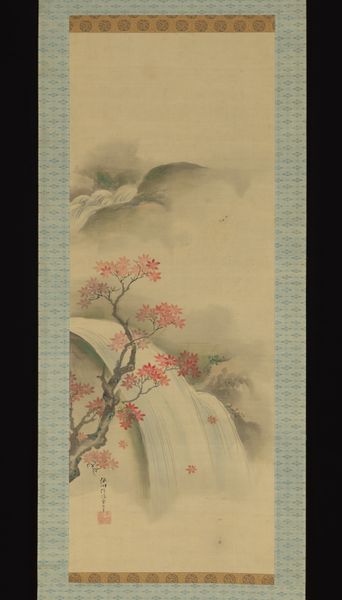

Dimensions: 44 1/8 × 17 3/8 in. (112.08 × 44.13 cm) (image)77 3/8 × 22 5/8 in. (196.53 × 57.47 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

Kano Sōtoku's ‘Lions’ is made with ink and colour on silk. The painting presents a vertically-oriented composition dominated by muted earth tones, accented by the striking reds of the flowers and the lush greens of the foliage. The lions themselves are rendered in warm shades of orange and brown, creating a focal point in the lower half of the silk. The composition is structured by the verticality of the palm trees, which frame the scene and draw the eye upward, while the lions anchor the lower portion with their poised stance. This arrangement is not merely decorative; it engages with a tradition of symbolic representation where animals embody virtues and natural elements reflect cosmological principles. The lions, rendered with anatomical ambiguity, suggest a symbolic rather than realistic intent, challenging fixed meanings of representation and engaging with new ways of thinking about perception and cultural values. This reflects a broader artistic concern with destabilizing established visual categories. The formal qualities of the artwork – its composition, color, and symbolic representation – function as part of a larger cultural and philosophical discourse.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Two lions roam a tropical landscape, framed by a coconut tree and strange red and purple flowers. In the background, a rhinoceros lingers by the water. Even while communication and trade between the rest of the world and Japan was highly restricted, the Japanese were eager to learn about life beyond the seas. Dutch traders brought Western publications, such as Johann Jonston’s Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri (1650), to Japan. Printed, translated versions of the books were disseminated through Japanese publishers and became popular among artists, who often used illustrations in Western books as models for paintings and drawings. While we do not know the source of the lions, the rhinoceros’s source is clear. Though small in scale, the creature resembles that of German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut from 1515. Dürer never saw a real rhinoceros; instead, he based his illustration on written descriptions. The image was reproduced repeatedly within Europe in prints and books, including Jonston’s Historiae naturalis. First presented as a gift to the fourth shogun, Tokugawa Ietsuna, in 1663, Historiae naturalis was kept in the library until the eighth shogun, Yoshimune, rediscovered it. Enea VicoItalian, 1523–156716th centuryRhinoceros, 1548EngravingThe William M. Ladd CollectionGift of Herschel V. Jones, 1916 P.468

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.