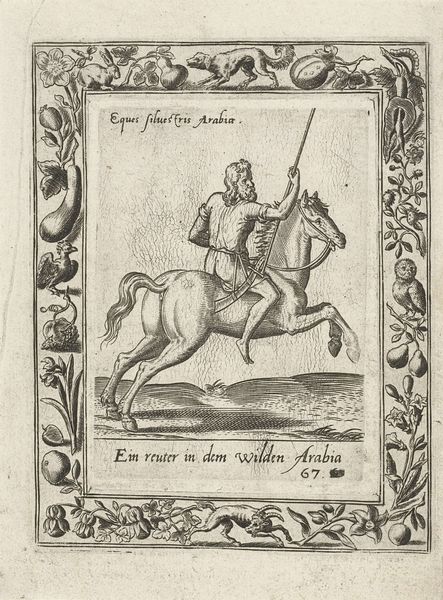

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

form

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 106 mm, width 75 mm, height 141 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Abraham de Bruyn created this engraving, "Arabische edelman en zijn vrouw te paard," or "Arab Nobleman and his Wife on Horseback" around 1577. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. The figures, presented within a very ornate frame, strike me as exceptionally still. Editor: The stark, graphic nature immediately makes me think of the power dynamics at play. The nobleman is placed forward, a symbol of status and dominance, yet the image is rife with the orientalist imaginings of the time. Curator: Indeed. De Bruyn, working in the late Renaissance, was likely less interested in factual representation and more engaged in constructing a visual statement about cultural difference. Consider the attire: The tall headdress on the man, her full covering, meant to signify otherness to European audiences. It perpetuates stereotypes. Editor: Absolutely, and consider the weight of horses as symbols of conquest, trade, and social stratification throughout history. The woman riding behind speaks volumes; where does she fit within the social discourse of the artwork and the represented culture? It almost acts as propaganda through subtly presented symbols. Curator: The artist uses the established symbolic language of portraiture and courtly display to depict people from another culture. There is no engagement with Arab subjectivity. The use of “Arabische” as a descriptor lumps a very diverse region into a monolith for European consumption. Editor: Note the almost illustrative quality, resembling depictions in illuminated manuscripts or early printed books. De Bruyn translates real-world observations through established visual rhetoric, reinforcing preconceived ideas about gender roles and cultural identity through clothing, posture and relative placement. This work operates within, and strengthens, the structures of early modern Europe. Curator: The framing devices further emphasize its status as an exotic specimen observed, and contained, for European viewers. We see the depicted figures mediated, classified, and controlled through representation. Editor: The enduring power of images. It prompts us to consider what purpose these early prints had and continue to have and what narrative functions they serve within collective memory. Curator: Thinking about how images historically portray power is vital. The act of observing carefully always leaves us more critical than when we start. Editor: A potent reminder that these early portrayals built narratives that, sadly, persist even now, in a globalized setting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.