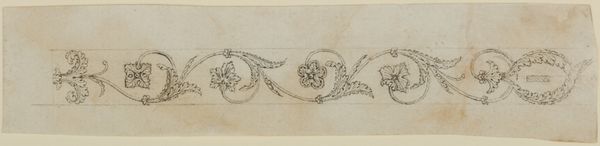

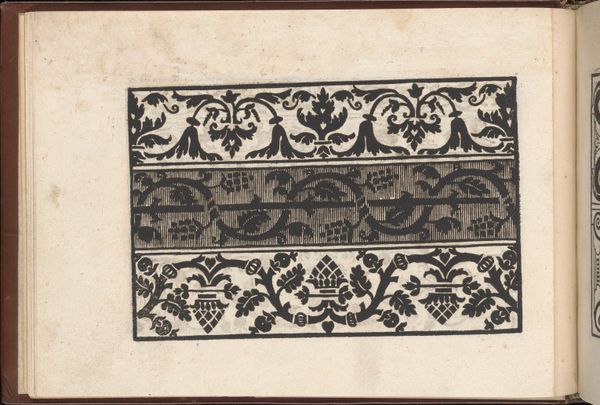

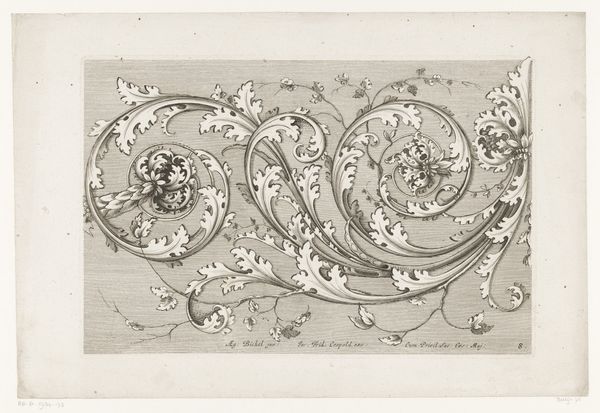

drawing, coloured-pencil, print

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

coloured pencil

Dimensions: Sheet: 5 1/4 in. × 8 in. (13.3 × 20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to “Joaillerie: Album of Jewelry Designs, Page 8,” an anonymous print and colored pencil drawing from 1770, currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Oh, this is delightful! I’m immediately struck by the sepia tones; they give it such an antique, almost melancholic feel, like pressed flowers in a forgotten book. It’s simple, elegant… and brown! Curator: Indeed. Sepia evokes a sense of timelessness, doesn’t it? This aesthetic was particularly influential in the later Neoclassical revivals, a kind of self-conscious return to a mythic origin through austere and "correct" representations. Floral motifs, of course, symbolize beauty, growth, and often served as coded messages in the 18th century, depending on the specific flower. Editor: But let’s consider the labor involved! This wasn’t a mass-produced piece, but rather a delicate, handmade design meant as a template. Look at the precise linework! Someone meticulously rendered each leaf and petal, considering the inherent worth of craft and adornment, perhaps even the hierarchy of jewelry production. Curator: And perhaps contemplating the social impact, the meaning-making and status granted by ornament? It isn't simply about manual production but an appeal to something more symbolic, perhaps even, daresay, sacred? In its deliberate rendering, there is a quest to imbue jewelry with significant identity and power. The ribbon weaving in and out is, on a basic level, merely decorative; yet, in a broader context, what meanings does a symbol like a ribbon tie? Editor: The ribbon itself points to connection. A material bond. Also, thinking about it functionally—a design on paper ready for the hands of goldsmiths and lapidaries. Imagine the transfer of skill, of human touch, from paper to precious metal. This image embodies the social relations of production in a burgeoning market of luxury. Curator: That connection translates to the social sphere. As we reflect on these details, it becomes a powerful insight into our social connections to adornment. And as these objects fade away into historical contexts, images remain in cultural memory to inform material practices. Editor: Very beautifully said, it helps to put labor in conversation with larger social questions!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.