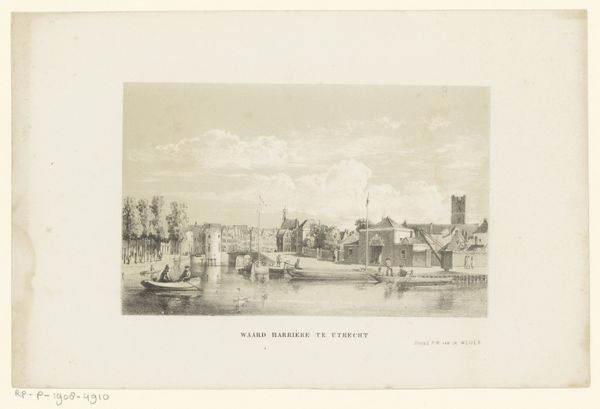

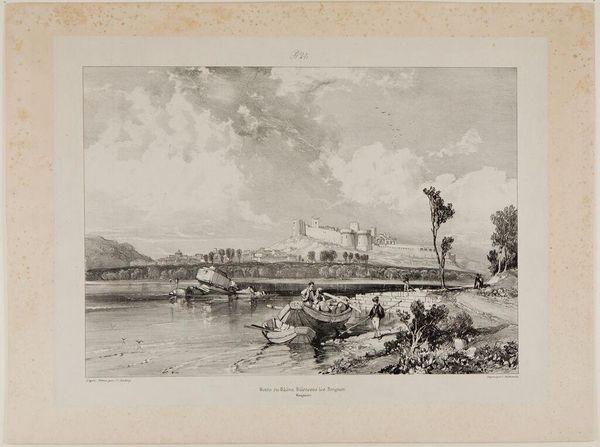

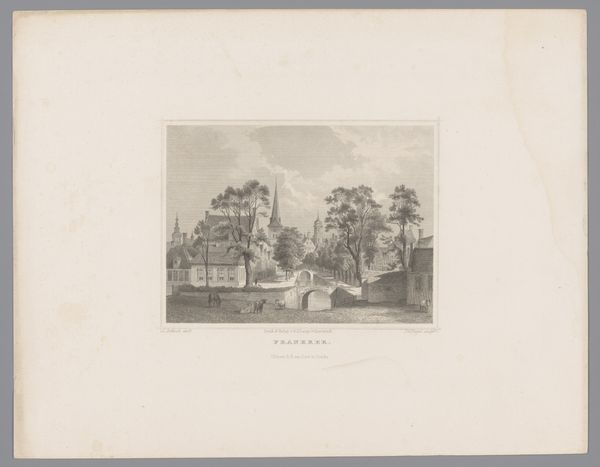

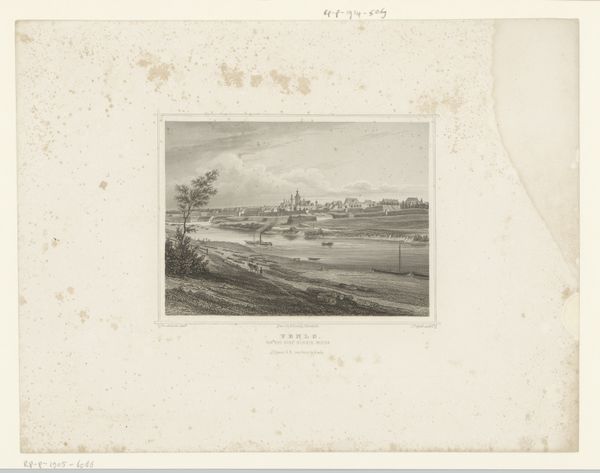

print, photography

#

aged paper

# print

#

landscape

#

white palette

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

realism

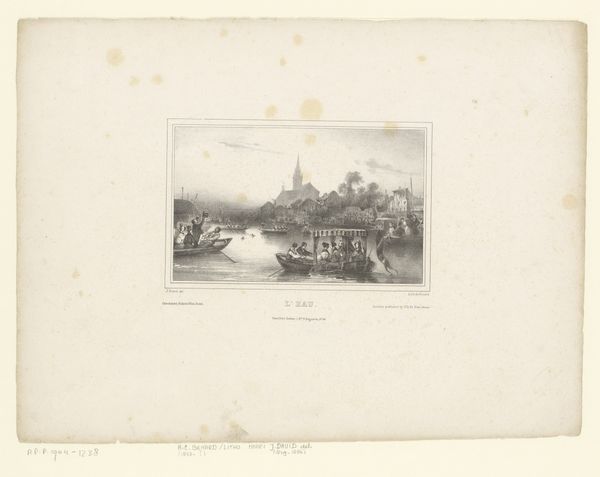

Dimensions: height 161 mm, width 257 mm, height 318 mm, width 478 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is "De sluis van buurtgemeenschap Dockumer Nieuwe zijlen," or "The Lock of the Dockumer Nieuwe zijlen Neighborhood" by Thomas Martin Staas, created in 1883. It is a print, most likely a photograph of its time. Editor: There’s a quiet stillness here, a melancholic air almost. The pale greys and faded details give it an ethereal quality. The architecture has a solidity that the tonal range softens into an almost dream-like vision. Curator: Given its creation in 1883, and that its theme is cityscape, this artwork may tell the story of Dutch urban development and its impact on the environment and societal structures, with an invitation to the viewer to consider issues around labor, urbanization, and even sustainability in an industrialized context. Editor: Looking at it through a lens of cultural memory, the lock serves as a powerful symbol of connection and control. The waters, contained and channeled, remind us of how societies try to manage natural resources and human interactions, how we control flow and movement to achieve particular outcomes. This visual lexicon persists even today. Curator: Absolutely. And beyond just management, control, who has it? Who is affected? These early structures facilitated trade and potentially consolidated wealth into the hands of a few. Thinking of that bridge, whose path is made easier? Is this advancement for all? Or just the privilege to connect and overcome limitations? Editor: You're right, these imposing architectural forms might speak of societal divisions and hierarchies, but also of the shared endeavor to build and shape a communal space. The bridge becomes not just a passage, but also a visual representation of access and opportunity... or perhaps its absence. Curator: It makes you reflect on how seemingly neutral landscape art from the period, and this feels somewhat rooted in realism, can actually embody such profound and complicated social and political realities. It highlights how vital it is to deconstruct even the most everyday of imagery. Editor: It shows the endurance of symbolic language across time, inviting us to decode and rethink the visual artifacts left for us to ponder their relevance in the modern times. What flows do we still try to manage and who profits most from their regulation? Curator: Precisely. Thinking about it now has changed the way I understand our past, present, and our possibilities moving forward.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.