Cased Pair of Double-Barreled Turn-Off Flintlock Pistols 1775 - 1825

0:00

0:00

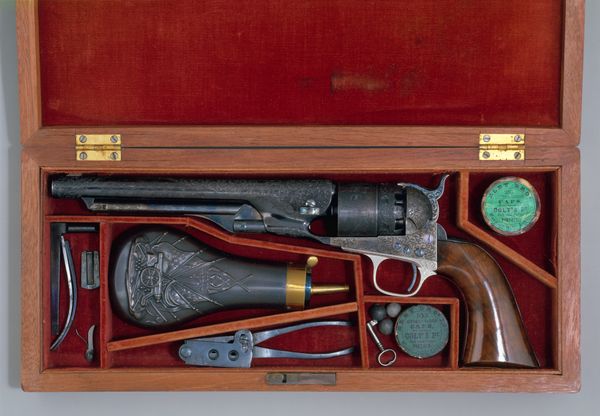

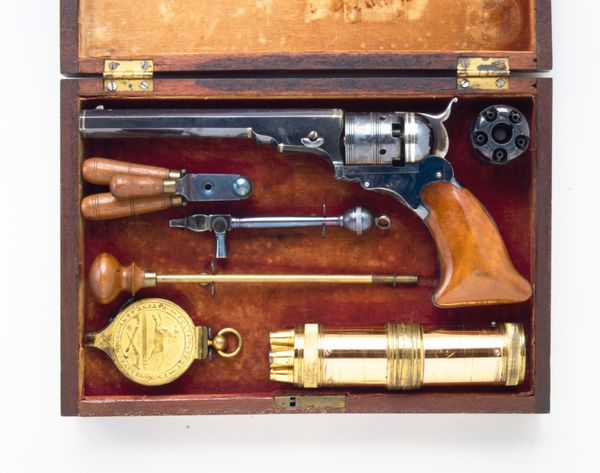

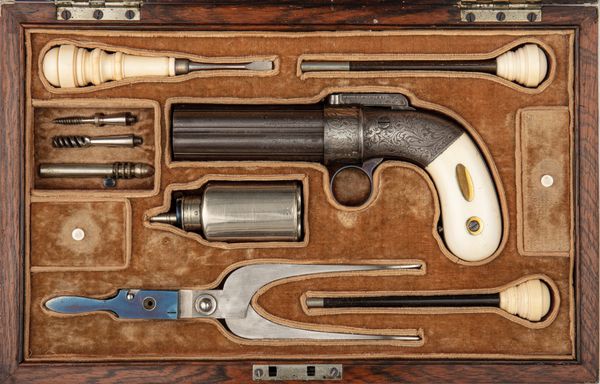

Dimensions: L. of each pistol 8 in. (20.3 cm); L. of each barrel 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); Cal. of each .46 in. (11.7 mm); Wt. of each pistol 1 lb. 5 oz. (600 g); bullet mould (28.196.6a); L. 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm); Wt. 4.3 oz. (121.9 g); wrench (28.196.6b); L. 3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm); Wt. 2.6 oz. (73.7 g); case (28.196.6c); H. 3 7/16 in. (8.7 cm); W. 11 1/2 in. (29.2 cm); D. 6 7/8 in. (17.5 cm); Wt. 2 lb. 15 oz. (1332.4 g)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have a cased pair of double-barreled turn-off flintlock pistols, crafted sometime between 1775 and 1825, possibly by Jean Lepage. The materials—metal, gold, and carving—caught my eye; it’s this juxtaposition of luxury with lethal force. How do you interpret the presentation of such violent objects as fine art? Curator: This pairing definitely demands interrogation. It exists at an intersection of power, artistry, and violence. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, firearms transcended their utilitarian purpose. They became status symbols, emblems of wealth and authority intricately tied to gendered performance of masculinity and control, don’t you think? Editor: I do. There’s an undeniably performative element to the detail. The engravings aren't just decorative, are they? Curator: Absolutely not. Consider what imagery would adorn these weapons: classical motifs like the Medusa head—references to mythic power, to the wielding of life and death. Think of this object in the hands of its owner—someone who is participating in enforcing and benefitting from colonial structures. It’s beautiful, certainly, but also deeply implicated. Can you see how these objects reflect broader sociopolitical currents? Editor: I think so. The artistry almost seems intended to sanitize the violence. The luxuriousness seems like an active distraction. It forces a dialogue about value, both artistic and human. I didn’t consider the gender performance aspect initially, but that adds another layer. Curator: Precisely. Recognizing these complex and contradictory narratives allows us to critically engage with art history, interrogating whose stories are told, how they’re told, and to what ends. What will you take away from studying this artwork? Editor: I think I’ll question more often why an object exists, and for whom. Thanks for bringing this critical perspective to the discussion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.