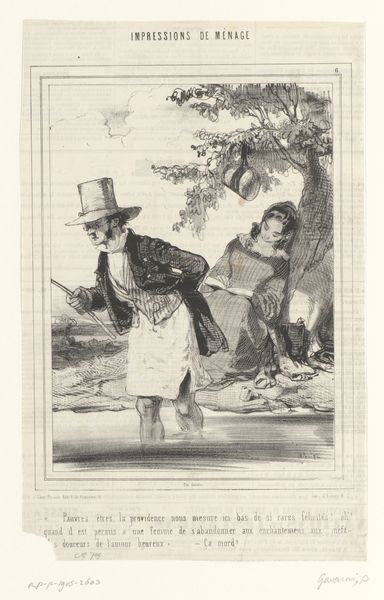

drawing, print, pencil

#

pencil drawn

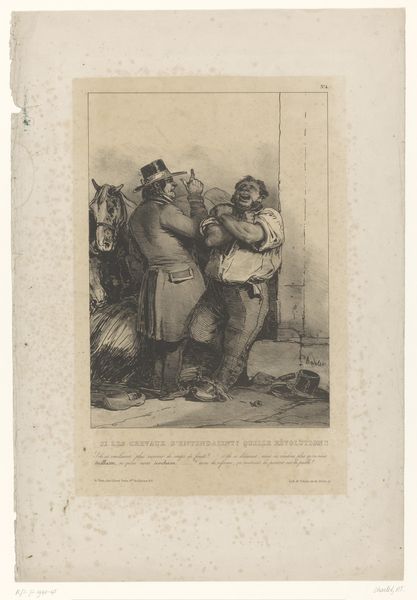

#

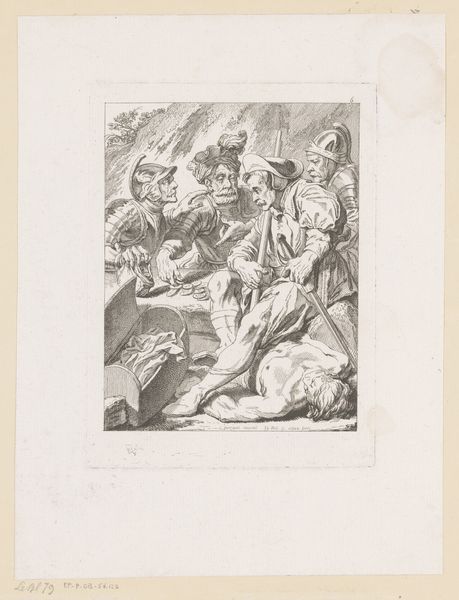

drawing

#

shape in negative space

#

light pencil work

#

negative space

#

shading to add clarity

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

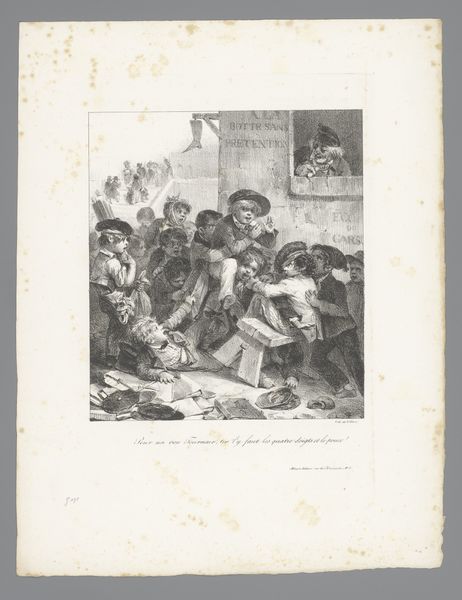

romanticism

#

pencil

#

limited contrast and shading

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

#

remaining negative space

Dimensions: height 311 mm, width 262 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

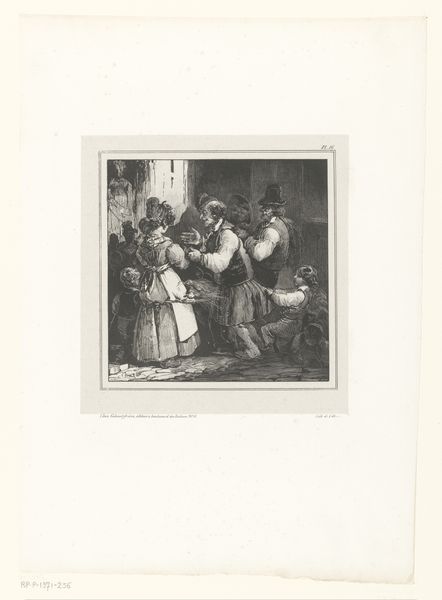

Curator: Here we have Gustave Doré’s "Dansfeest in de Elzas," or "Dance Festival in Alsace," created around 1849. It's a print, most likely based on a pencil drawing. What strikes you immediately about it? Editor: It's quite hazy, almost like a memory. The use of pencil creates a sense of immediacy, yet the scene itself seems distant. I am intrigued by its lightness. Curator: It's interesting that you pick up on that haziness. Considering Alsace’s contested history, caught between France and Germany, that visual ambiguity might mirror the region's complex identity. Think about the folks engaging in their traditional dress... who gets to decide whose traditions are legitimate, and who benefits from this display? Editor: Indeed. And the sheer labor involved in producing a print like this for mass consumption can not be dismissed. Each line carefully etched, multiplied for distribution - it speaks to a deliberate intention to disseminate this image, shaping perceptions of Alsatian culture. Curator: Exactly. The very act of depicting this “folk” festival is fraught. Is it celebratory, or is it a form of cultural appropriation? Also, Romanticism favored emotional expression; what emotions does it evoke in you when seen in our contemporary moment? Editor: Well, besides its materiality, this image and scene strikes me as rather detached from the actual labor and life of Alsatians in 1849. Where is the toil? The materials of their dresses appear idealized. And the very framing serves as a barrier between the viewer and participants. I ask myself what that labor dynamic means for us here today. Curator: It highlights how representation, especially visual representation, can perpetuate power dynamics. It’s a reminder to critically examine not just what is shown, but also who is doing the showing, and for what purpose. Even what looks to be an unassuming folk scene participates in broader historical currents, social constructions and complex issues of power. Editor: Yes, the romanticized surface veils deeper socio-economic relationships embedded in the very act of its making and its presentation to the masses. Curator: Looking closely makes visible that even in seeming celebrations there's much at play. Editor: Indeed. A material and social artifact to prompt crucial discussions today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.