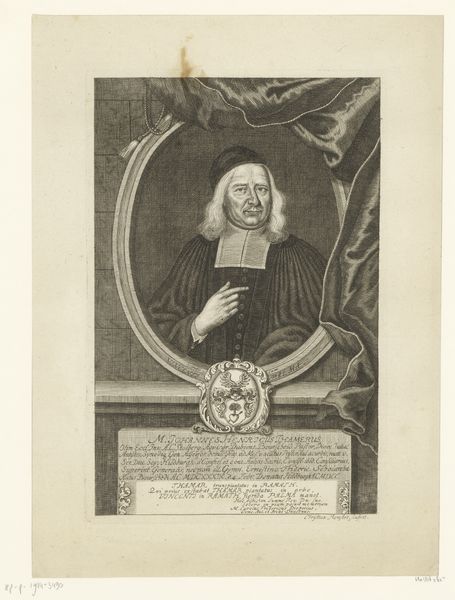

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 400 mm, width 277 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the sheer craftsmanship in this engraving. The level of detail is extraordinary. Editor: Indeed. This is "Portret van Jacob Langermann," dating from around 1738-1740, currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It's an engraving by Christian Fritzsch of a senator of Hamburg. Looking at him, he seems very self-satisfied, doesn't he? Curator: The layering of the image is what stands out to me. The senator framed in what seems to be an oval portrait hanging within the space, plus the added embellishments of a draped curtain, elaborate frame, and supporting architecture makes for a multi-tiered process. It speaks to Baroque extravagance. The labor and materials signify the social standing being depicted. Editor: Definitely, all this to amplify his status and perhaps deflect attention away from the sitter himself. Langermann's privileged position is underscored. In the 18th century, class and gender constructs rigidly defined the opportunities for individuals. It is the Age of Enlightenment, but it also still a period of incredible social divide. Who got to have their portrait memorialized, who controlled these images and their narratives? Curator: Those engravings involved highly skilled labor, a formal printing press with heavy mechanical parts, inks sourced from varied pigments… it's not just an image but also the outcome of collaborative effort. How might this method have influenced art distribution and popular accessibility? Editor: An important question. Certainly, the ability to reproduce and distribute such images, however limited compared to today, could begin to influence public perception of figures like Langermann and what he represented. Were prints like this simply propaganda, or did they serve a broader function in constructing social identity? Curator: Maybe that depended on who was purchasing, trading, or obtaining them. Was it other elites consolidating a shared idea of status, or middle class merchants who wanted to associate themselves with status by purchasing smaller prints, which made such imagery highly desirable and profitable, creating a much wider market for distribution? Editor: Right, these items became aspirational tools. This one print gives rise to so many fascinating questions about that moment in history! Curator: Agreed! I appreciate seeing beyond the simple image and engaging with the physical creation of this historical object. Editor: Me too – understanding its historical contexts offers new entry points for viewers in the 21st century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.