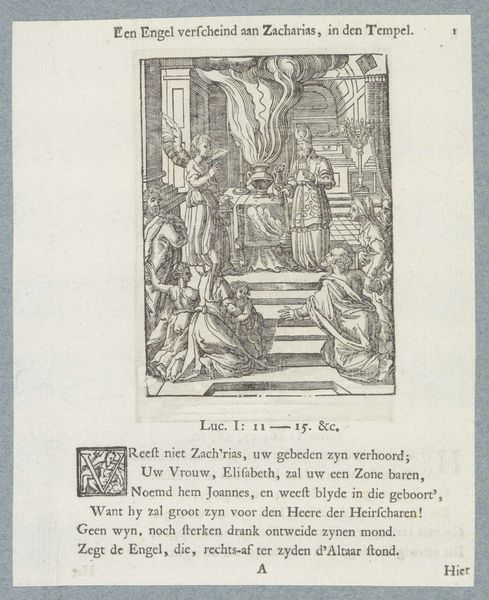

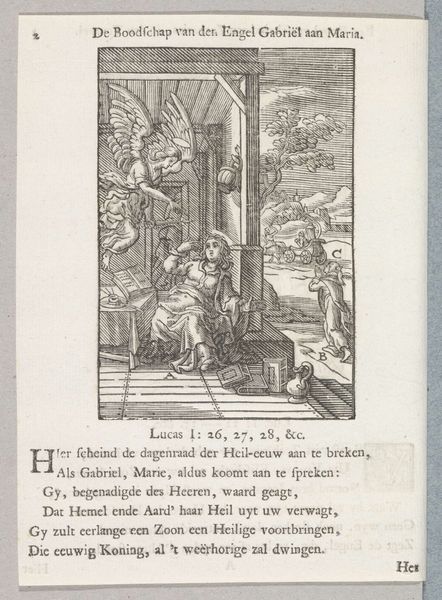

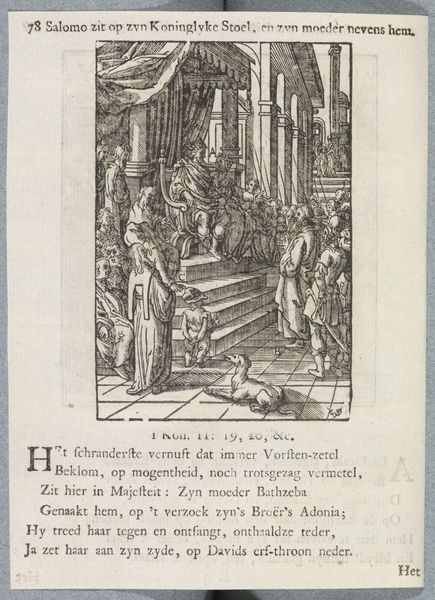

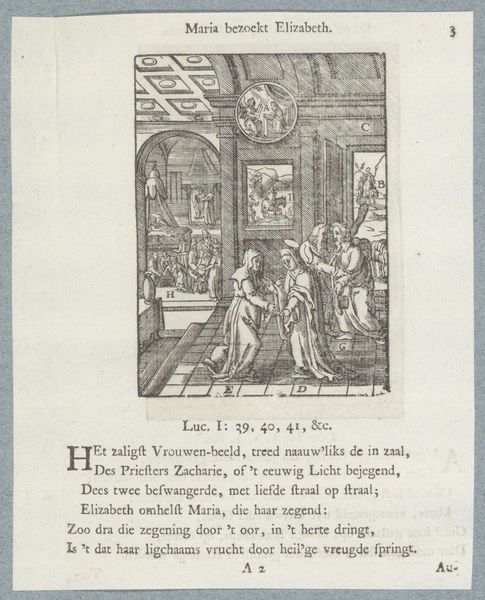

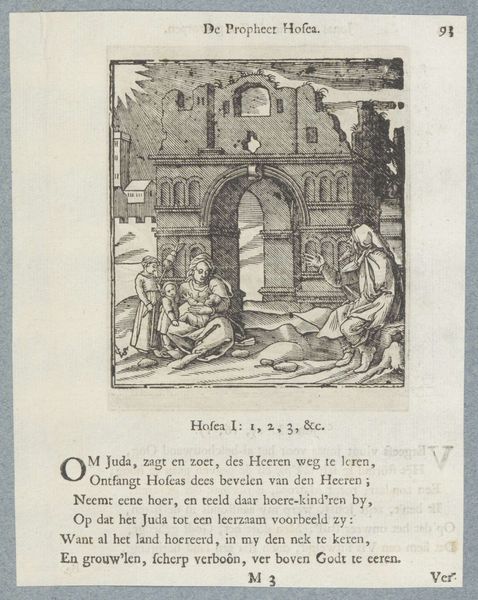

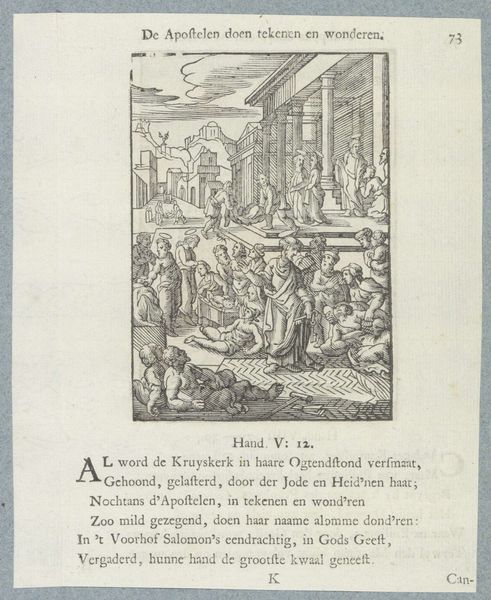

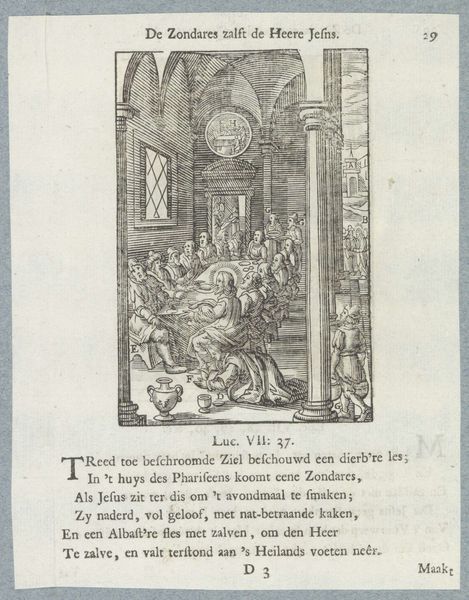

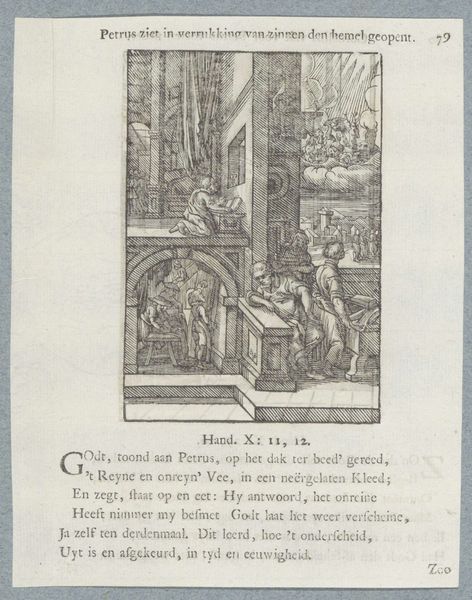

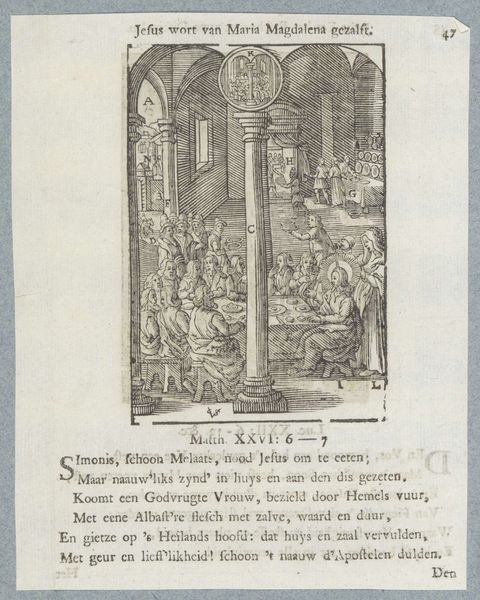

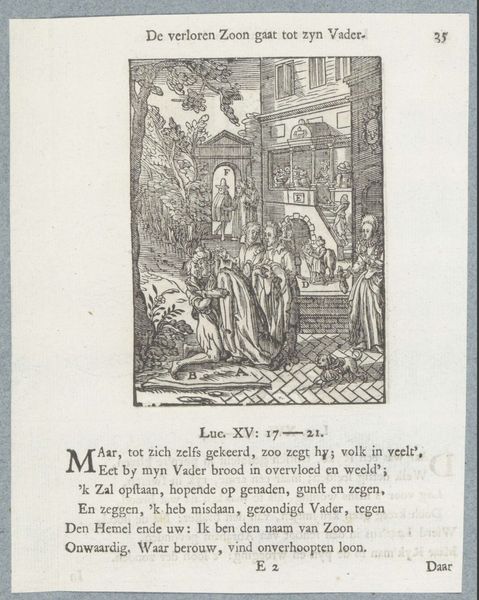

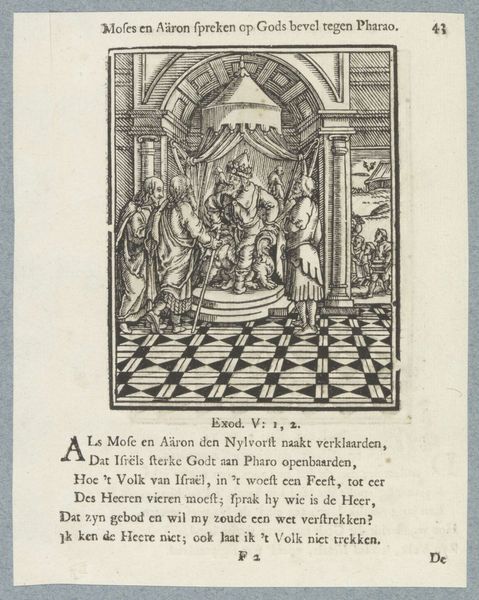

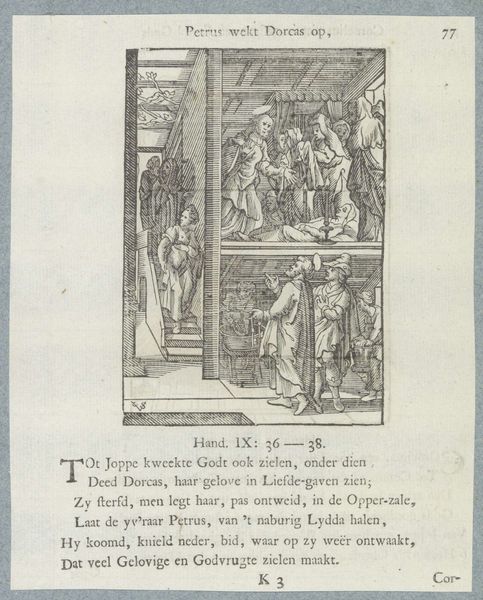

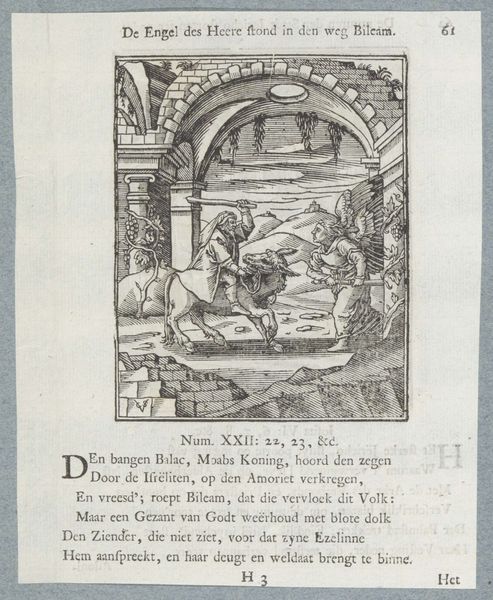

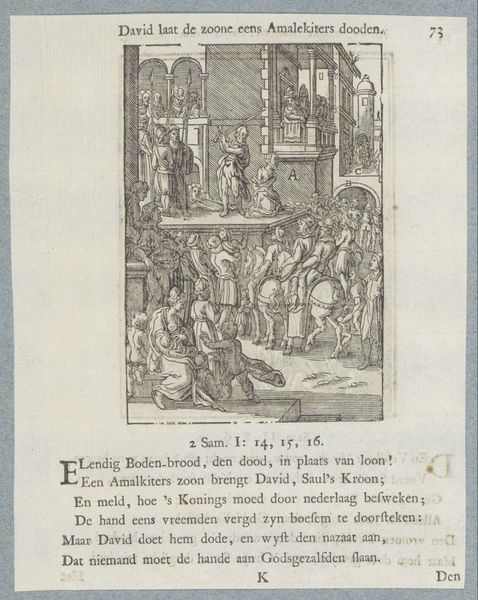

print, engraving

#

aged paper

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

christ

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 75 mm, height 170 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's delve into this engraving titled "Christus en de Samaritaanse vrouw bij de put," or "Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well," attributed to Christoffel van (II) Sichem. It dates from between 1629 and 1740. Editor: My initial reaction is struck by how this small print feels epic in scope, presenting such a significant encounter, but also how the style invokes distance, creating an austere and remote aura around the scene. Curator: Yes, the composition, typical of Baroque prints, certainly invites symbolic interpretation. Note the well itself, a traditional symbol for enlightenment and spiritual nourishment, placed centrally to highlight its thematic importance. Then we have Jesus in conversation with the Samaritan woman. It's a story loaded with themes of cultural and gender boundaries being crossed. Editor: Precisely, and that's where its potency lies for me. In its time, this imagery disrupted social norms. It presents a narrative where Jesus challenges the established hierarchies by speaking to a woman, a Samaritan no less, offering her living water, an allusion to spiritual salvation that transcends social status and traditional religious divides. This challenges patriarchal and sectarian dogmas that would have excluded her. Curator: The image's enduring impact rests on these radical inclusions. You know, water here operates as a layered symbol. While in ancient philosophy, water symbolizes both knowledge and cleansing, the water that Jesus offers transcends mere earthly understanding; it’s eternal, regenerative. Editor: Absolutely, it speaks to profound transformations, not only individual salvation but broader social emancipation. This simple well becomes a focal point for revolutionary potential within its context. The landscape, even as just background decoration, it a scene of societal structure and norms of the period which further emphasize the impact of Jesus giving his time and grace to a Samaritan women who would be seen as a societal outcast. Curator: Thinking of the visual elements, it's interesting how the text beneath functions too; while acting as a title of sorts, it's very wordy for a printed text meant to pair with the image and be swiftly legible to all readers. Editor: It reminds me that what the print does with the figures of Jesus and the Samaritan is extend grace towards a part of the public that could be literate and consuming this visual content and who was likewise treated with far less support by the societal structures that benefited wealthy men. I think the image becomes far more active when placed in that context, the very purpose of religious images is for the consumption and conversion of more religious devotees. Curator: Indeed. Exploring the use of symbols in religious art often uncovers the complex interplay between visual storytelling, spiritual aspiration, and philosophical inquiry. Editor: And through those visual cues and narrative choices, art becomes a battleground, advocating silently for inclusion, equality, and change, all wrapped in a beautiful image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.