painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

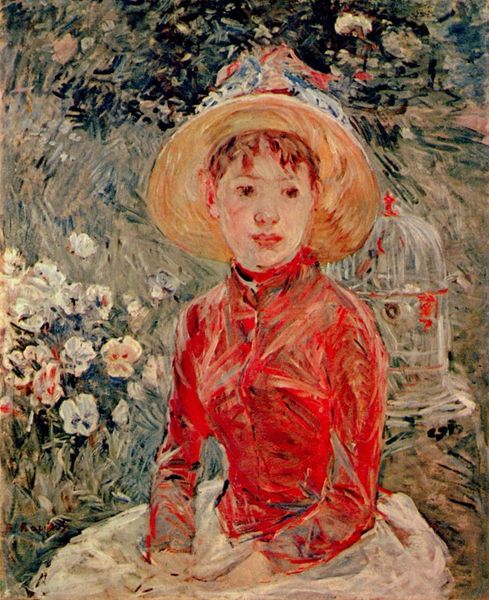

Curator: Berthe Morisot’s "Portrait of Paule Gobillard," created in 1884, captures a delicate moment. Look at how she portrays her subject, it’s almost ephemeral. Editor: There’s a palpable sense of quietude, a kind of serene intimacy. The blurred edges contribute to a very dreamy quality. The palette is dominated by greens, whites, and a lovely deep purple which seems at once somber and stylish. Curator: Style definitely plays a part. Gobillard, who was also Morisot's niece and a fellow artist, is adorned in finery. It offers an intimate look into the lives of women artists at that time, deeply embedded in the domestic sphere. We glimpse their fashion and cultivation of an artistic circle within that space. Editor: And let’s consider Morisot's distinctive brushwork—those visible, broken strokes, how she renders the fleeting effects of light and shadow with oil paint. Notice especially the treatment of the background. It merges seamlessly into the sitter’s attire and the subject herself. It suggests Morisot was more invested in atmosphere, affect, and gesture rather than illusionistic representation. Curator: Precisely, the portrait exists at a fascinating juncture in the history of the Salon system. Here's an artwork clearly invested in portraying the nuances of modern life through an engagement with Realism but with Impressionistic techniques of handling paint that signaled new developments in painterly practices. Editor: We might even interpret this painting in relation to how Impressionism generally responded to an increasingly industrialized culture that also saw developments in photographic technology. With photography seemingly able to accurately capture reality, painting sought alternative means. The ephemeral treatment we see in the sitter and landscape might point to painting defining itself through that which photography couldn’t offer at the time—sensation. Curator: What you're highlighting makes me think about the economic side as well. It invites a question of Morisot’s agency and class status, as a female Impressionist, and as the one producing, not being produced by painting. It's crucial when thinking about production and consumption to understand that she was far from marginalized. Editor: That's so interesting! The work then transcends simply capturing likeness. Instead, we engage in its complex dialogue and social dynamics, which are at work on and off the canvas. Curator: Absolutely. It’s a painting that makes us reconsider our assumptions about labor, portraiture, and what Impressionism meant for women artists during the late 19th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.