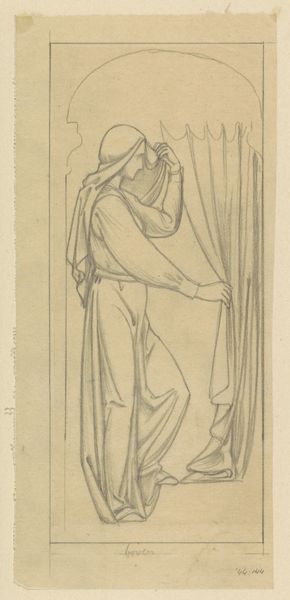

drawing, print, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 432 × 238 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us, we have George Romney’s "Figure of a Woman," created around 1776, rendered in ink on paper. It’s currently held at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its ethereal quality. The minimalist strokes and warm sepia tones create a sense of both strength and vulnerability. There's an unfinished air about it that draws you in. Curator: Indeed. Romney’s draftsmanship is key here. Note how he employs line—almost calligraphic—to delineate form, reducing it to its essence. The academic underpinnings are undeniable. It subtly invokes the neoclassical, even within the immediacy of the sketch. Editor: Precisely, and consider the historical context. Late 18th-century depictions of women, especially within Neoclassicism, were largely symbolic. The sketch presents a paradox; a figure who perhaps alludes to classical ideals of feminine virtue while seemingly resisting a rigid, defined space in representation. It begs the question, who was she and did Romney ever "finish" this representation? Curator: Interesting. What I observe is the considered compositional choice. The figure dominates the plane, while its surrounding paper allows the image breathing room. Consider its relation to similar ink studies by Romney—a clear continuation of style and methodology, but still self-contained. Editor: Yes, but let's also observe that Romney occupied an era defined by both political upheaval and shifting social mores, particularly the era of women's increasingly precarious rights amid a rising new bourgeoisie. How can one overlook the implicit power relations, despite its seeming restraint? Even these “unfinished” sketches communicate so much, because of what the incomplete parts represent of the relationship to representation at that time. Curator: Fair enough. Yet I’d urge a balance; one risks collapsing artwork into purely sociological data. We can still acknowledge its intrinsic mastery of artistic form, in the lines that build towards form and then immediately erase themselves with unfinished and sketchy details. It’s both suggestive and elusive. Editor: It is—elusive being key here. Ultimately, I think we must accept the tension of its openness. As much as Romney leaves undone structurally, historically speaking he speaks of the impossibility of “completing” a stable and fully legible representation of women, whether symbolically, allegorically, or historically. Curator: An argument well made. Indeed, the power of the "Figure of a Woman" perhaps resides precisely in its refusal to resolve itself definitively into either a purely formalist construction or a strictly contextual artifact. It’s that point of dialogue between intention and interpretation which enriches the piece and provides resonance. Editor: I agree. Romney invites viewers to find meaning in both presence and absence of meaning, thus, in an intellectual act of creating context and representation, to fill the structural voids on the page and in history itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.