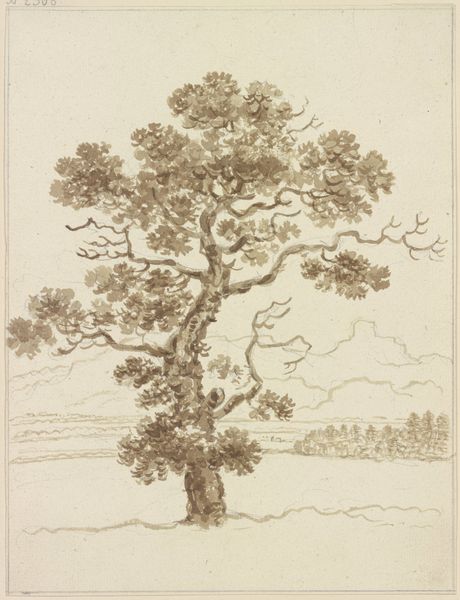

drawing, tempera, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

tempera

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

german

#

sketch

#

romanticism

#

15_18th-century

#

line

Copyright: Public Domain

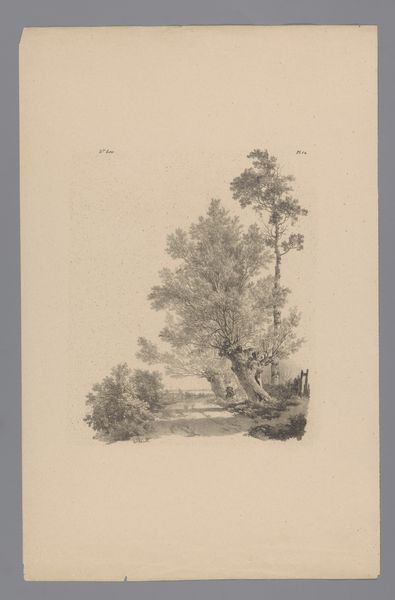

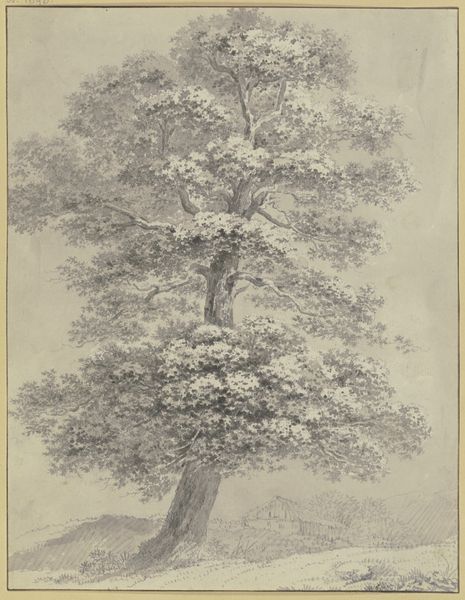

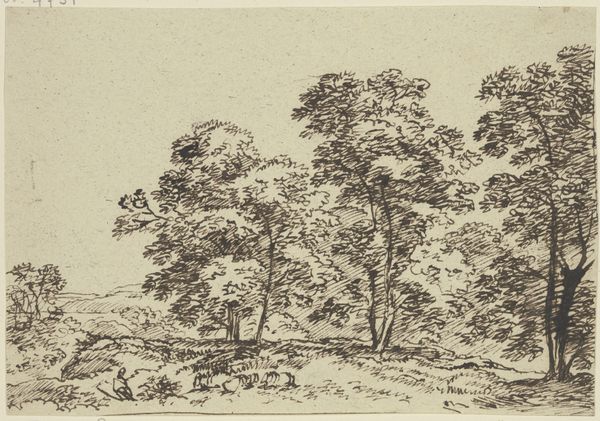

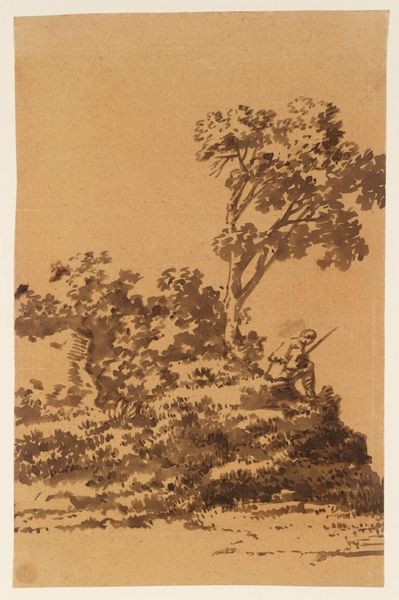

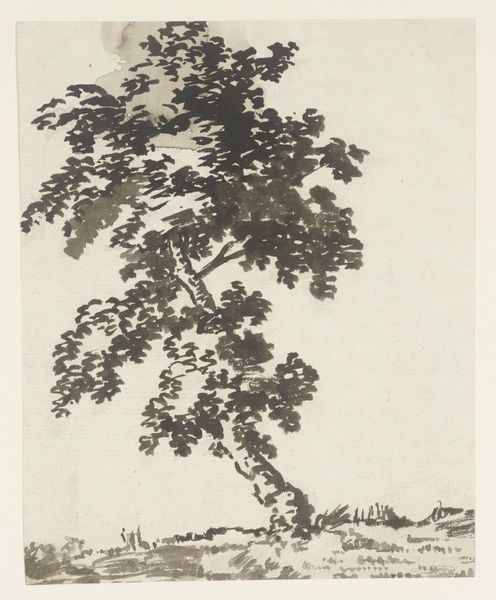

Curator: Well, what strikes you first about this landscape? Editor: It feels so quiet, almost melancholic. The sepia tones give it this aged quality, like a memory fading at the edges. It's incredibly simple, just a lone tree dominating the scene. Curator: This is "Landschaft mit einem Baum im Vordergrund", or "Landscape with a Tree in the Foreground," a work created by Friedrich Wilhelm Hirt, now held at the Städel Museum. While it's not precisely dated, scholars place it within the 18th century. Look at how Hirt used materials like ink and tempera on paper; that's central to appreciating the artwork. The physical process, the way the ink bleeds into the paper, gives it that ethereal feel. Editor: And consider this scene, placed into its broader historical context. Germany in the 1700s was going through incredible changes. What statement is Hirt making about the people by showcasing the land? Is this an affirmation of self, home, a reflection of political unrest, the impacts of industrialization? This singular tree, dominating the horizon line--is this Hirt grappling with Enlightenment values? Curator: Exactly! Think about where paper came from—the mills, the labor involved in its production. Then, the act of applying ink, the choice of tempera...it speaks to the artist's skill, of course, but also the economic and material realities surrounding art production. It allows us to engage with artistic tradition as both skilled and commodified work. Editor: Yes, I wonder about his choice to make the landscape so barren, though. The lone tree has so much symbolic potential in times of upheaval—resistance, resilience, or maybe even desolation in response to oppression. His placement of a central tree can reference not only German Romanticism's turn towards the relationship between nature and feeling but also the very specific social implications of this positioning in his homeland. Curator: These landscapes were often produced as independent artworks intended for sale in local shops, too—accessible art for a burgeoning middle class interested in nature and a degree of ornamentation, showing the art market trickling into other economic and social terrains. Editor: That's a brilliant point. It connects to consumption—who had access to images like these? What did it mean for people to own and display these renderings? Curator: Absolutely! Focusing on materials and techniques can broaden the scope and meaning beyond simple aesthetics. Editor: Ultimately, I think by interrogating the art, we ask ourselves the crucial questions: who is seen, who is not, and how has that changed (or remained stagnant) throughout the progression of our understanding of fine art? Curator: Precisely—a layered narrative that challenges what we see when viewing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.