Copyright: Public domain

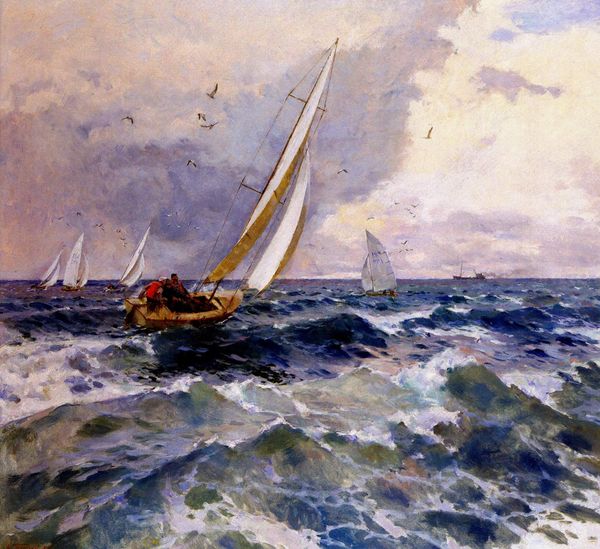

Curator: Looking at Eugène Boudin's "Rough Seas," created in 1885, one immediately confronts a powerful scene. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Overwhelming. I'm struck by how the oil paint seems to mimic the churning of the water and the weight of the storm clouds. You can almost feel the grit of salt in the air. How do the labor and material connect to the final work for you? Curator: Well, Boudin was quite the pioneer of painting en plein air. This method certainly played a part in capturing the immediacy of the coastal atmosphere of France, as the art market at the time heavily favored this style of truthful landscape depiction and commodified quick oil sketches and the rapid execution of detail. Editor: Interesting that it’s 'truthful', given how heavily the artistic market was involved in driving the value of en plein air style works and the physical labour involved in hauling the material outside the studio to the sea, how has that changed from previous, more atelier driven work? Curator: It created an opportunity for artists like Boudin to interact directly with his subjects and the weather, resulting in the work resonating with the French ideals and values. One can imagine that painting on-site gave rise to different ways of connecting with nature as subject in 19th-century French society. Editor: Exactly, there's an inherent risk when laboring and material conditions meet! The rapidly changing environment forced an engagement with impermanence. That hurried application, visible brushstrokes... they speak to a negotiation, a direct relationship between artist, paint, and the wildness of the sea. And think about how this challenged the established hierarchies within art production. Suddenly, capturing a fleeting moment, embracing the roughness of the materials, became valuable. Curator: Yes, Boudin's dedication to documenting real-life is visible, even with a painterly scene; his work helped bridge the gap between traditional landscape painting and the more radical explorations of his Impressionist colleagues. Editor: Ultimately, it underscores the idea that art is born out of process. What do you think the legacy of this form and work has meant for current practice? Curator: I think Boudin helped make plain-air work part of a public, accessible form in galleries and even reproduced widely—perhaps not exactly what he was anticipating when taking his kit out to sea. Editor: Perhaps not. It just speaks to a truth—no pun intended—that speaks volumes of nature’s true materiality through process and engagement of an artistic laborer in a particularly wild element.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.