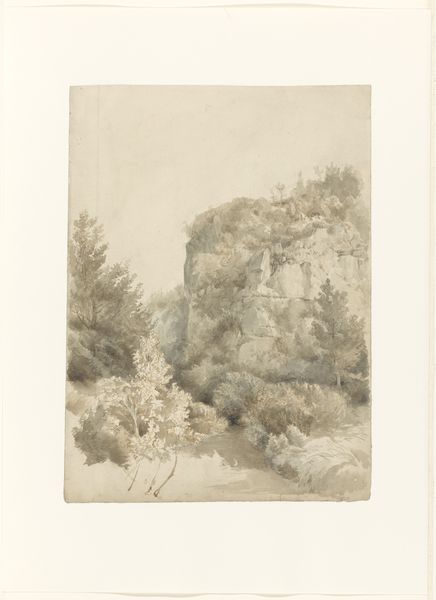

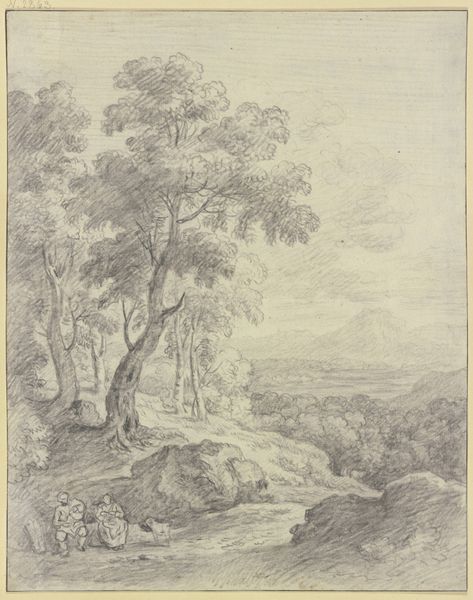

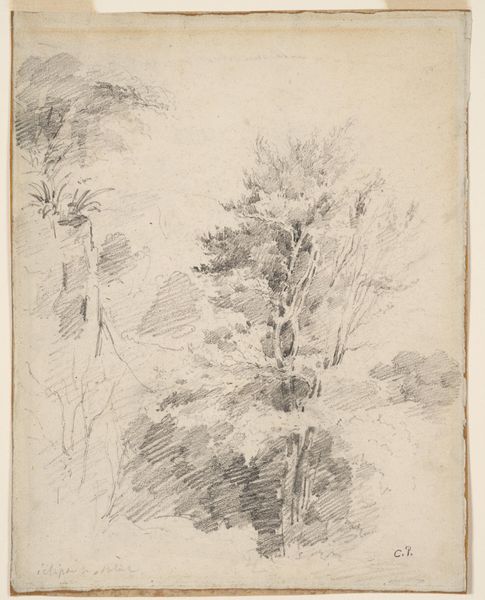

drawing, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

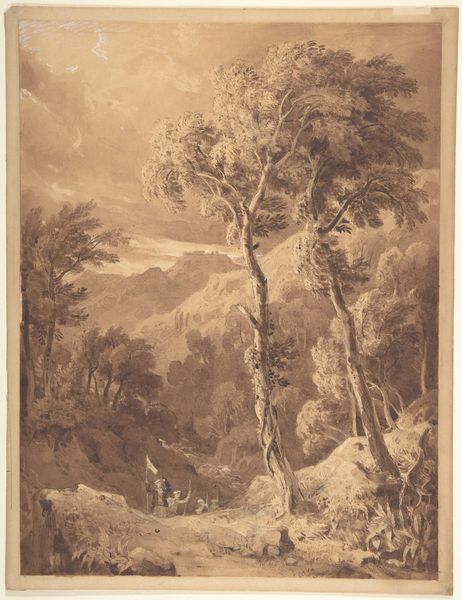

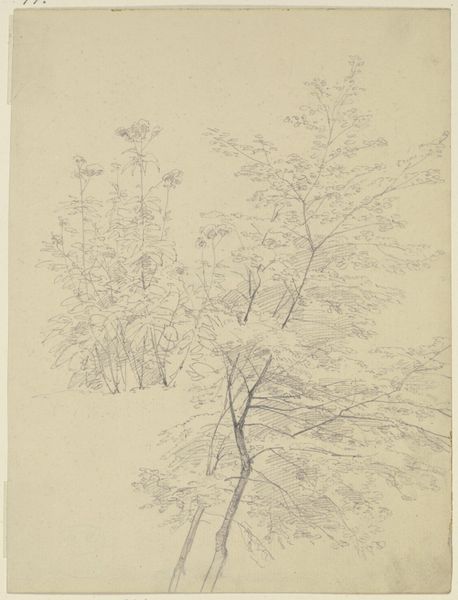

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

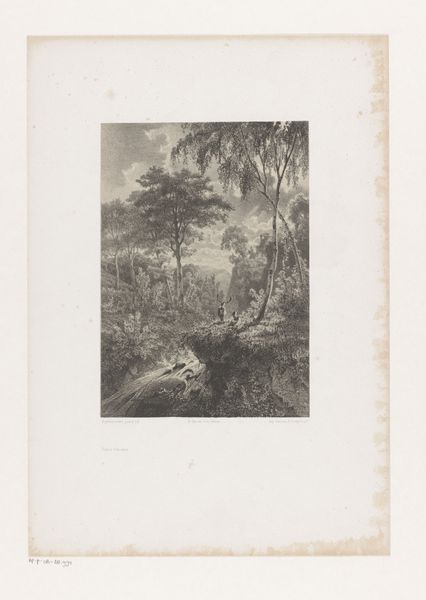

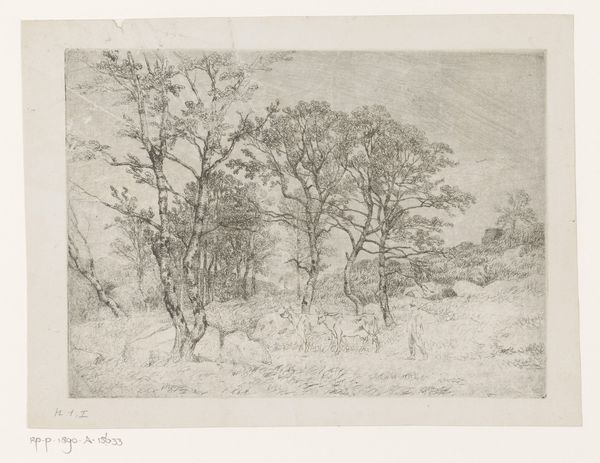

etching

#

pencil drawing

#

forest

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Dimensions: height 376 mm, width 295 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This captivating drawing, titled "Beek tussen hoge begroeide rotsen" or "Stream between High Overgrown Rocks", was rendered in 1838 by Barend Cornelis Koekkoek. Editor: The drawing just emanates this incredibly serene atmosphere; it feels almost meditative, like stepping into a silent dream. The contrast is gentle, giving it this incredibly subtle quality that I am drawn to. Curator: Absolutely. And you know, Koekkoek was a huge advocate of drawing "en plein air," so it really gives us this sensation of observing something that feels real but idealized. He found that experience in the regions along the Dutch/German border. The Romantic movement saw nature as the main means for expressing one's most intimate emotions, as well as historical ones. How do you view its broader context within that era? Editor: Landscape paintings were powerful political statements, revealing tensions and connections with specific land claims in ways still visible today. This one looks incredibly inviting and pleasant; one could definitely perceive it as nationalistic since it shows something so attractive. What really draws me to it, however, is how this natural representation has something to do with cultural assumptions. Nature can symbolize different concepts and feelings. What do you sense is symbolized by the density of the rocks? Curator: Hmmm, that is insightful! Koekkoek does capture the solidity of the rocks and how they serve to protect the stream—a vital water resource and the heart of the scenery. Perhaps the painting speaks to the importance of natural resources for a nation, suggesting an element of pride but also encouraging us to meditate on our connection with the Earth and with one another. Editor: Right. This isn't simply a "pretty picture," then; it reflects broader views about cultural identity and control over resources, particularly in this age. Do you think it provides a voice or point of view about any group in society, considering class and the romantic appreciation of the natural world? Curator: That's interesting. The painting shows what elites thought was most picturesque in nature at this time; not everyone would have had access to such an untouched region. Class could come into play here because landscape art and tourism served elitist interests and activities. The artist probably did not intend that when the painting was created, but the historical reality cannot be denied, especially considering landscape history. Editor: Beautiful. I leave with the unsettling reminder that aesthetics, such as landscapes, are anything but apolitical; let us recognize that any experience of it needs critical thought as well. Curator: And maybe, in embracing this artwork’s multifacetedness, we might even glean wisdom for navigating our own place within the natural world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.