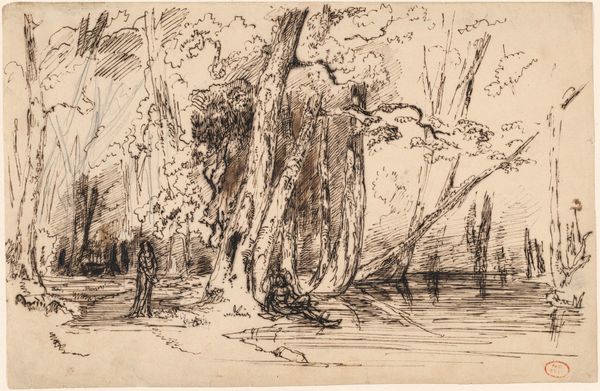

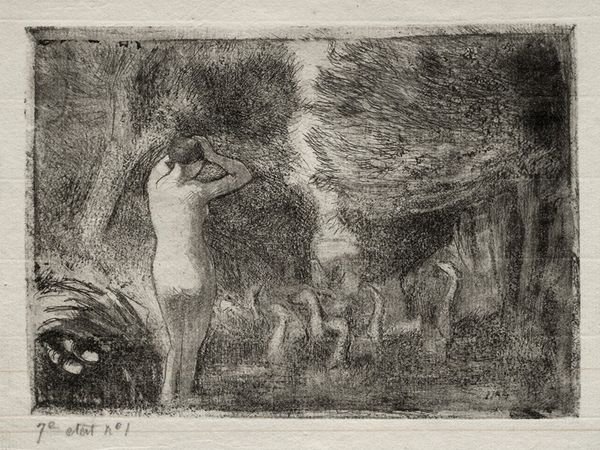

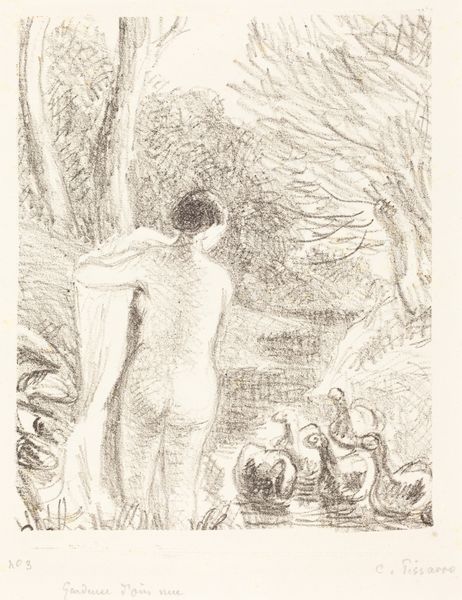

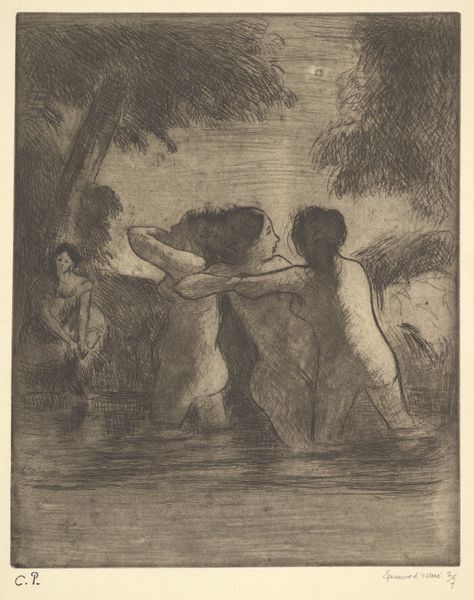

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 148 mm, height 140 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We're looking at "Bathing Boys in a Forest Pond," a pencil drawing by Max Liebermann, dated sometime between 1857 and 1935. There's something very raw and immediate about it, almost like a snapshot. What do you see in this piece? Curator: This drawing offers us a glimpse into the evolving understanding of boyhood during a period of significant social change. Consider the historical context: as industrialization increased, childhood became increasingly idealized as a space of innocence and freedom from labor. How does Liebermann's depiction of these boys in nature resonate with that ideal, or perhaps challenge it? Editor: I suppose it depends on how we interpret the figures. Some seem to be frolicking freely, while others are partially obscured. Curator: Exactly. We have to also examine whose childhoods were idealized and who had access to this perceived idyll. Were working-class children, children of color, granted the same freedom to be carefree in nature? Liebermann, as a Jewish artist working in a society grappling with growing antisemitism, would have been acutely aware of social hierarchies and exclusion. Does that awareness, or a critique of it, manifest in the drawing for you? Editor: I hadn't considered it in those terms. I was just seeing boys playing, but framing it within those historical and social dynamics really shifts my perception. The contrast between light and shadow also contributes to this ambiguity. Curator: It’s that interplay of visibility and invisibility that interests me most. Whose stories get told, and whose are marginalized or erased from the dominant narrative? By encouraging a more nuanced reading, can we unpack the complex power dynamics embedded in even seemingly innocent scenes like this? Editor: It’s fascinating how a simple drawing can be a site for these broader social and political questions. It's changed how I see art history. Curator: Art, like life, is a layered and complex dialogue. Questioning, always questioning, is the only way to see those layers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.