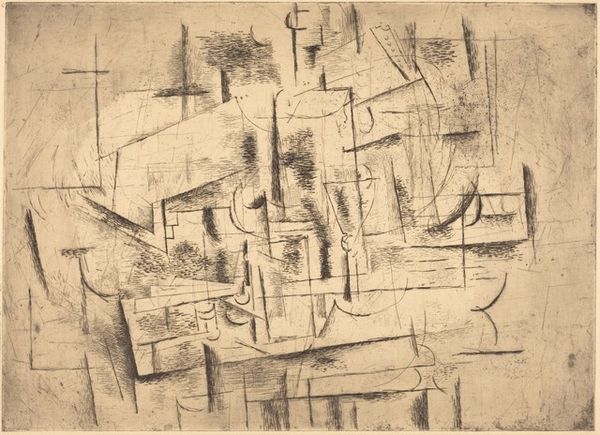

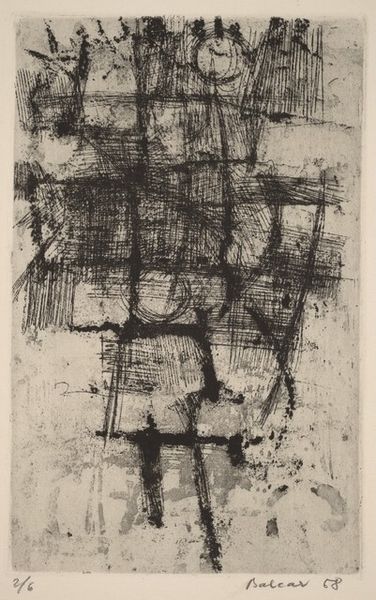

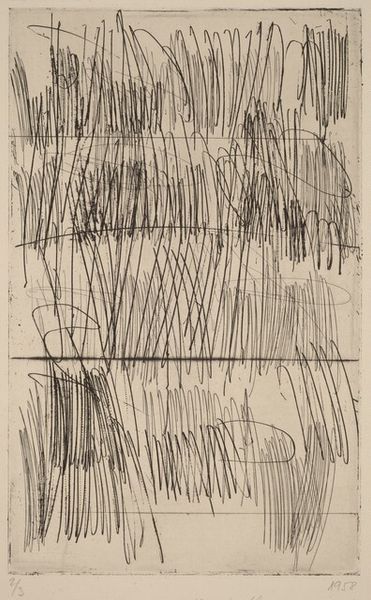

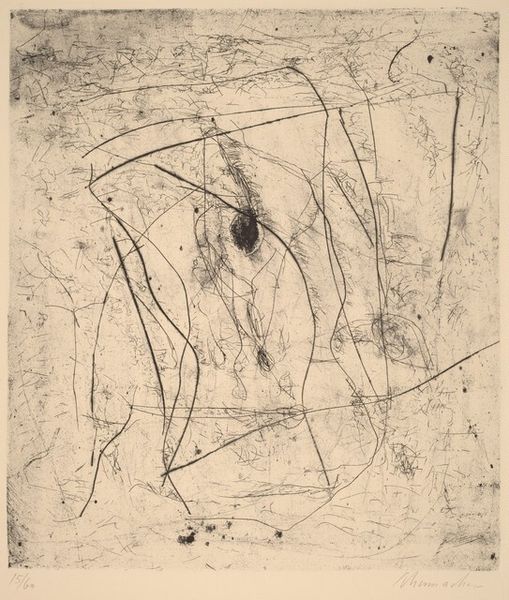

drawing, graphic-art, print, etching, ink

#

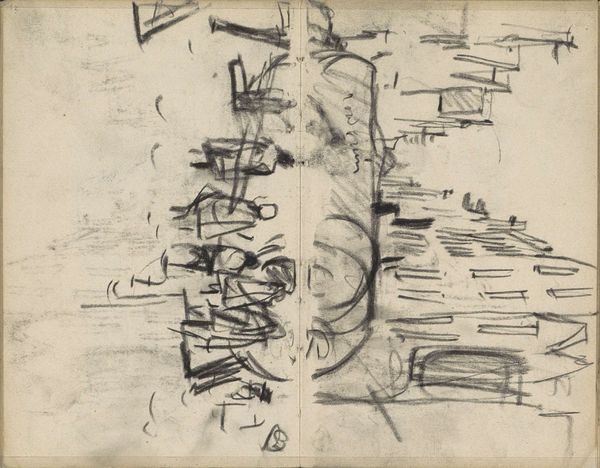

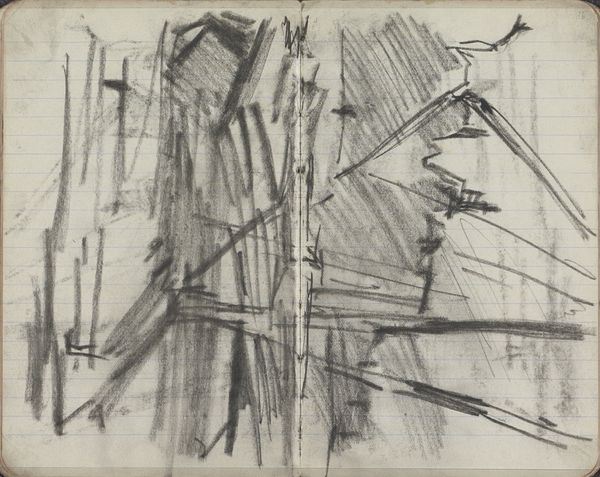

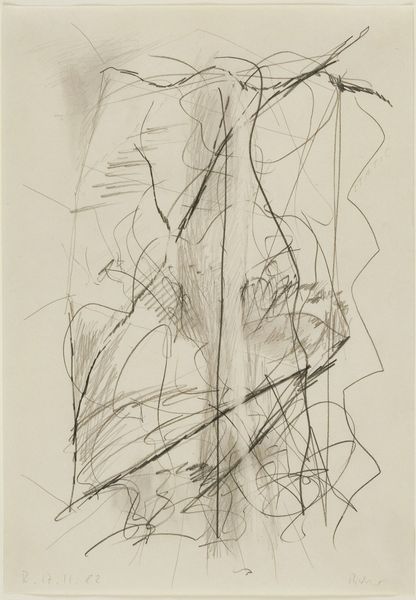

pen and ink

#

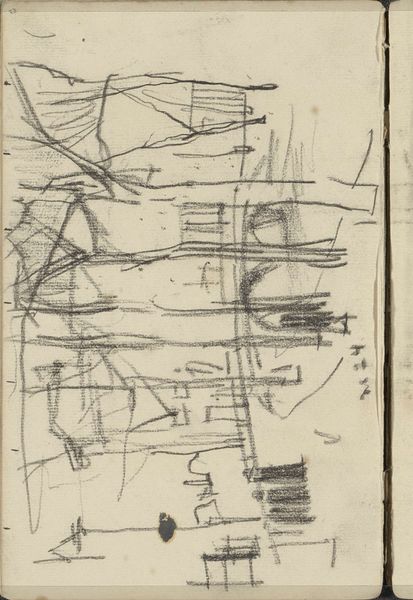

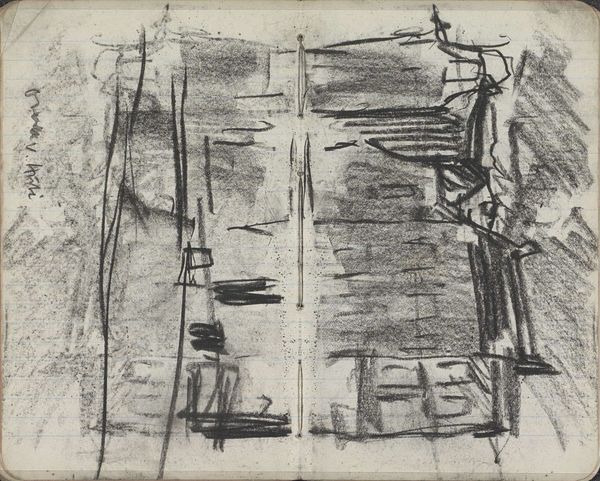

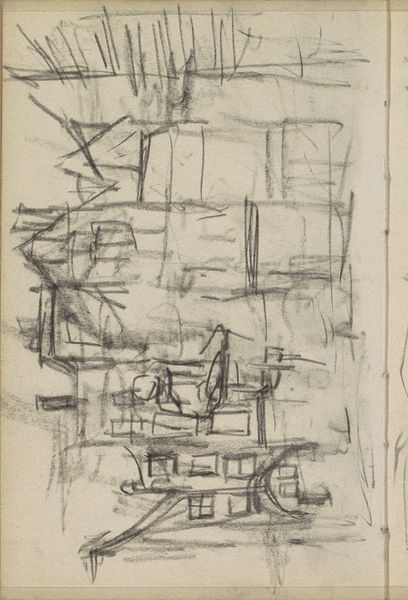

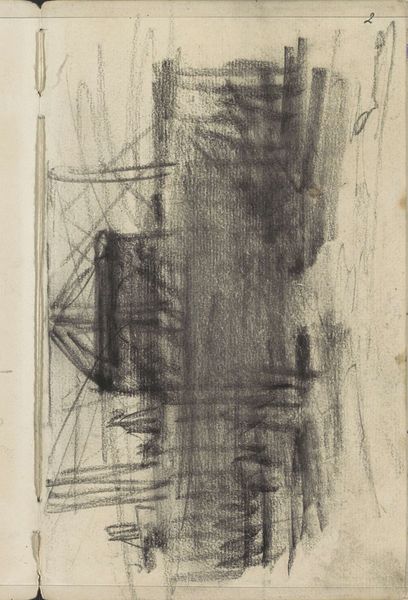

drawing

#

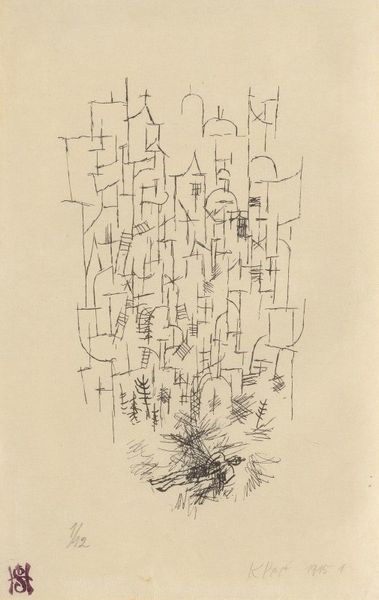

graphic-art

#

cubism

#

ink drawing

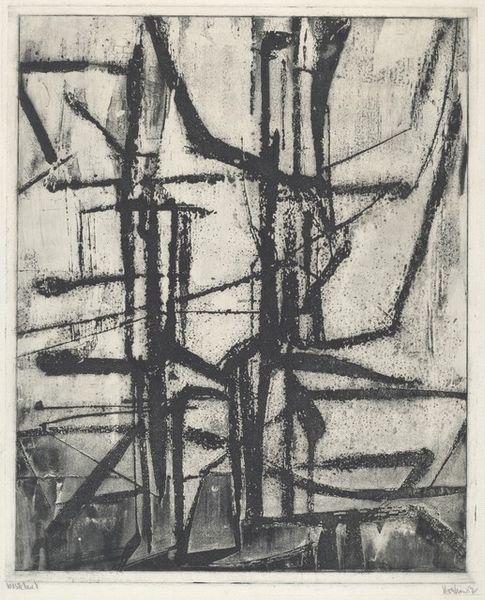

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

etching

#

ink

#

geometric

#

abstraction

Dimensions: plate: 46.5 × 33 cm (18 5/16 × 13 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Here we have Georges Braque's 1911 etching, "Bass." It’s all these intersecting lines and subtle shadings, a very intricate sort of geometry. It feels…almost like looking at something shattered and then carefully reassembled. What’s your take on it? Curator: It's interesting you say "reassembled," because that speaks to the crux of Cubism’s project – to dissect conventional ways of seeing. Braque, alongside Picasso, were really challenging the art world and its institutions. Think about how art was displayed and who it was displayed for; this wasn’t salon art destined for wealthy homes. "Bass," being a print, democratized the image to a certain extent, making art more accessible. Editor: Accessible in the sense that it could be widely distributed, perhaps, but is it really accessible visually? All of those fragments... it’s hard to decipher, isn’t it? Curator: That’s where its politics become even more intriguing. Consider the implied viewer: Braque assumes a level of visual literacy, pushing against passive consumption. He is less interested in representation, and far more interested in provoking critical engagement. Do you notice the words incorporated? Editor: "VIN" and "BASS" - are these clues to something specific, like a type of wine, or a musical reference? Curator: Exactly. It’s like Braque is pulling apart our very relationship to the object itself – the letters suggesting the label on the bottle or musical instrument. But what happens to the work’s authority or message when we *can't* decipher it completely? Is the artist playing a role in this deliberate ambiguity? Editor: So the 'difficulty' is part of its statement – almost daring us to engage and grapple with what we're seeing and our own expectations. Curator: Precisely! It reminds us that art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It lives in the world, shaped by and shaping social and political landscapes. Editor: That reframes my initial viewing entirely. I was focusing on the abstraction, but now I see the commentary woven into its very structure. Curator: And perhaps this makes even us question the role we play now – what responsibility do we as interpreters bear to connect these past statements to current conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.