drawing, print, paper, pencil, chalk, graphite

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

classical-realism

#

paper

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

graphite

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 348 × 265 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

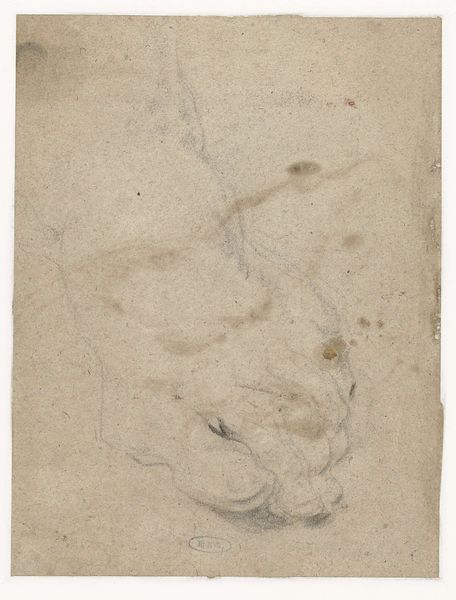

Curator: Before us is Anton Domenico Gabbiani's rendering of the "Head from Laocoon Group." A piece executed with pencil, chalk, and graphite on paper. What are your immediate thoughts when you observe this image? Editor: Distress. The head is lost in a storm of lines. It reminds me of sketches of faces you might find near the end of old psychiatric evaluations, moments of intense turmoil barely held on the page. Curator: It is a powerful study, isn't it? Gabbiani’s work allows us to peek into the artistic process of engaging with classical antiquity. "Laocoon," of course, embodies suffering. The original sculpture’s discovery in 1506 had a profound effect on artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, so you feel its emotional weight echoing through this drawing centuries later. Editor: Absolutely, I feel like its legacy casts a long shadow, literally shaping perceptions of heroism and agony for centuries. Seeing Gabbiani's study highlights not only the artistic engagement, but also the cultural baggage that comes with depicting extreme suffering. This drawing isn’t just a technical exercise; it’s a confrontation with inherited trauma. How do we depict such scenes responsibly? Can we, in fact? Curator: These sketches, exercises—consider them visual debates with the antique. Artists sought to distill the essence of ideal form and expression. The reproduction of classical sculpture helped standardize the western idea of art as tethered to older, often white and masculine models. Editor: Exactly, so the image's presence here in the Art Institute has resonance beyond its beauty as a drawing. Its position raises questions of representation, canon formation, and who gets to define ‘classic’ and on what terms. A white, masculine struggle, of course, is elevated to universality, even as the world’s myriad other suffering faces are ignored, overlooked, or exoticized. Curator: This study reminds us that engaging with art is an active dialogue—not just with the artwork itself, but with the values and history it represents. It is a constant negotiation between the past and the present. Editor: So, by engaging critically with works like this, we acknowledge the complex relationship between art, power, and representation. Looking at art becomes an opportunity to see beyond idealized narratives, recognizing who is centered—and who is systematically erased.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.