drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

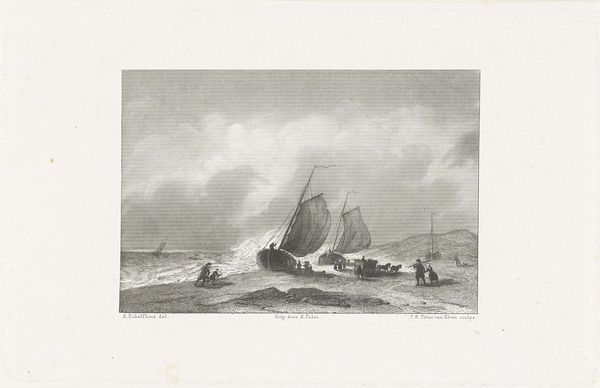

Dimensions: Image: 5 5/8 × 8 11/16 in. (14.3 × 22.1 cm) Plate: 7 7/16 × 9 15/16 in. (18.9 × 25.2 cm) Sheet: 12 11/16 × 16 3/4 in. (32.2 × 42.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

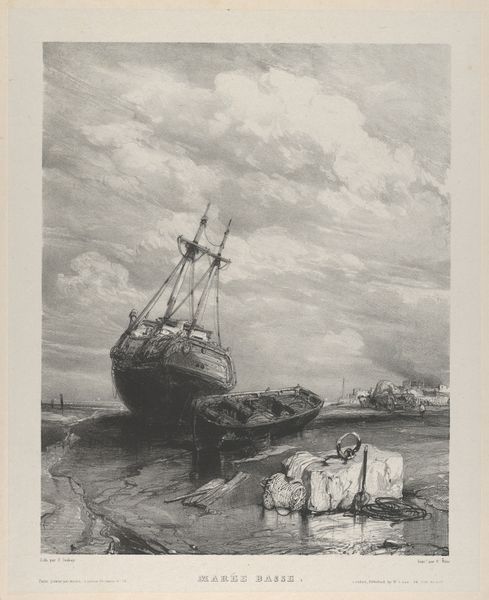

Curator: Here we have "A Sea Beach," an etching by David Lucas, dating back to 1830. It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What's your initial reaction to it? Editor: My immediate thought is melancholy. It’s the gray palette, of course, but also the figures feel so small against the vastness of the sea and sky. They appear weighed down somehow. Curator: It’s interesting that you say that. Lucas created this etching based on a work by John Constable. Consider the historical context: Constable was deeply interested in accurately depicting the natural world, but also capturing the emotional response to a scene. How would this resonate in British society at the time? Editor: Well, this was a period of immense social upheaval—the rise of industrialism, the erosion of traditional ways of life. A piece like this, showcasing the hard work and fragility of life connected to the sea, becomes a powerful comment on the changing landscape. Look at how close those figures on the boat are standing to each other – a sign of close working quarters, an embrace of collaboration and shared purpose. Curator: Exactly! And the etching process itself mirrors this idea of replication and dissemination of art to a wider audience. Rather than a unique painting only accessible to a wealthy patron, prints could circulate, spreading Constable’s vision – and Lucas’s interpretation of it – further afield. Do you believe that art is a class signifier? Editor: Inevitably, art access becomes political. Take note of how the ships take up a significant proportion of the composition and are the largest things on display. It feels deliberate, almost like it's trying to draw attention to the value of shipping trade. But look closer and there are multiple fractures to its representation such as the turbulent clouds. Curator: Lucas's skill in rendering atmospheric effects using only lines and tones is quite remarkable. It really encapsulates the Romantic sensibility toward the sublime. A landscape that overpowers us in the face of nature's grandness. Editor: True, there’s definitely an awe of nature, but there’s also a human narrative embedded here. I can't help but see the potential for activism in art like this—drawing attention to the livelihoods at stake, even today. Curator: Indeed. It highlights the complicated interplay between individual and societal perspective—between the sublime power of the sea, and the socio-economic power on shore. Editor: Yes, art history should embrace intersectional narratives and how works continue to resonate, impacting dialogue on critical issues related to race, class and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.