painting, print, watercolor

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

painting

# print

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

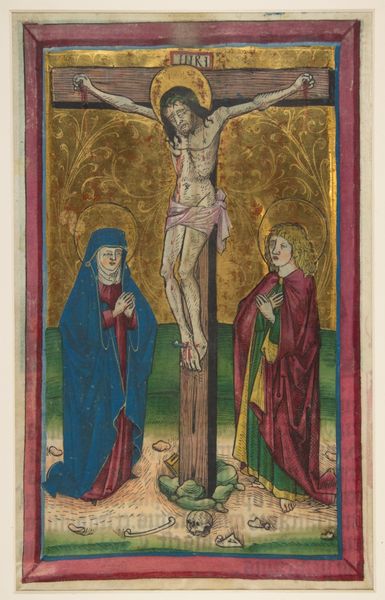

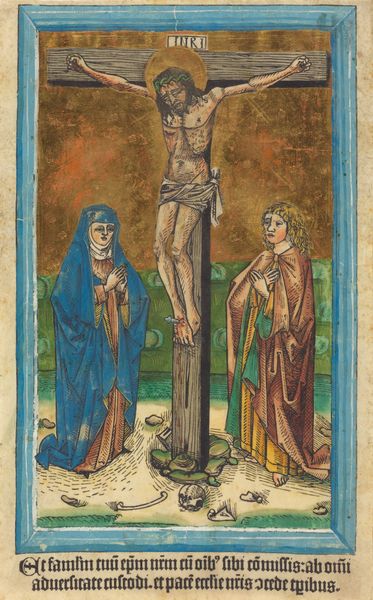

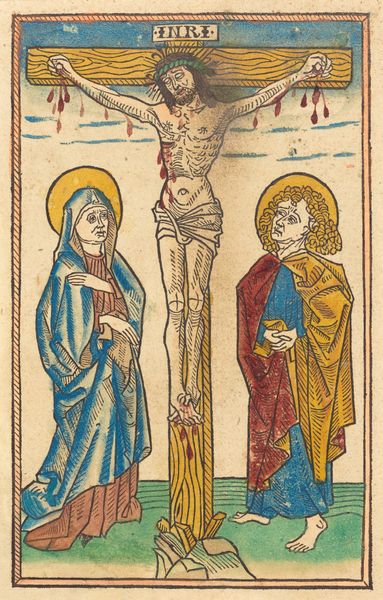

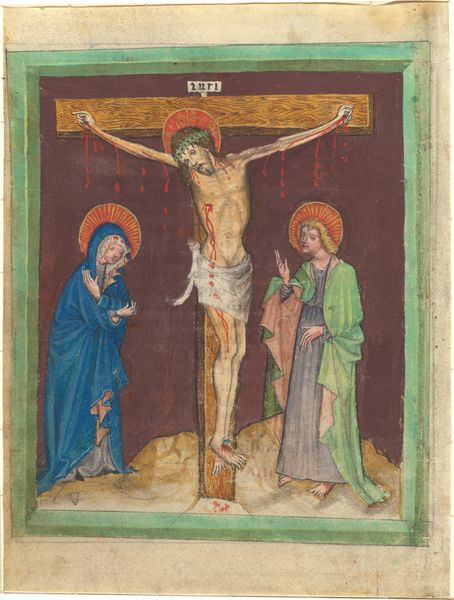

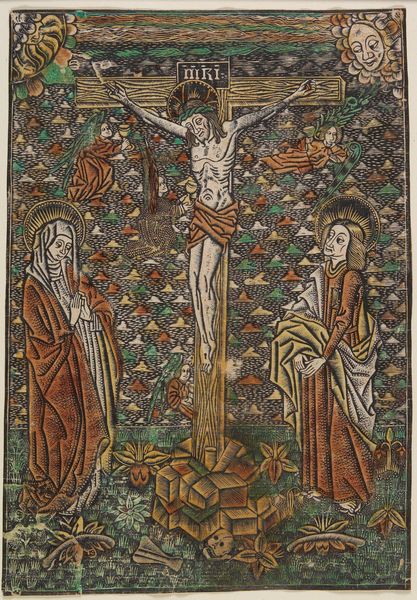

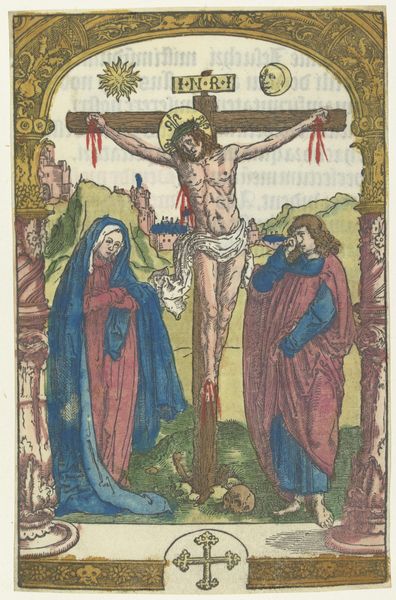

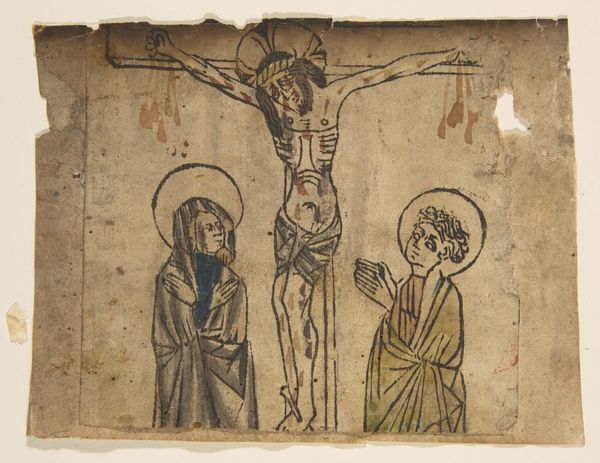

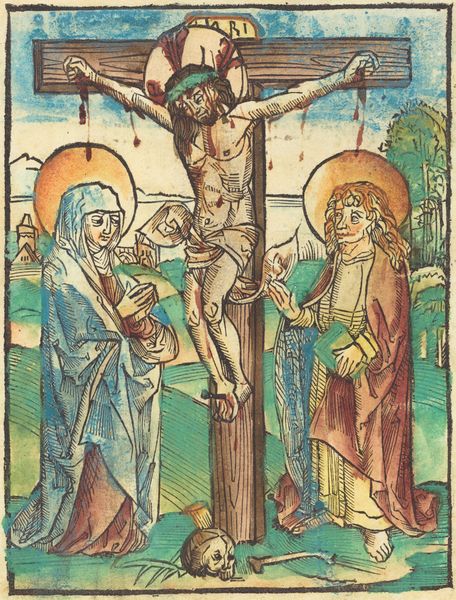

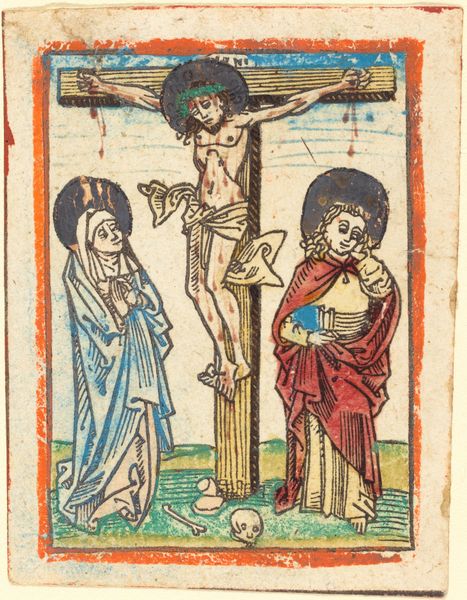

Curator: Before us, we have an early watercolor print, “Christ on the Cross,” dating back to around 1460 by an anonymous artist. Editor: It’s quite small, isn't it? Almost feels like a personal devotional piece. And immediately, I'm struck by how the materials betray a certain rawness—the way the color bleeds. Curator: That rawness lends itself well to the spiritual tenor. Notice the positioning of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist at the foot of the Cross, they exemplify the collective mourning of humanity. Their halos act like spiritual signifiers. Editor: And how are these pieces made? The texture seems uneven; tell me, were such prints widely available at this time, impacting popular devotional practices through reproduced imagery? How was labor distributed in their production? Curator: It's possible it was part of the block book phenomenon, which means each page, text, and image, would have been carved from a single block. And the imagery? It follows established visual tropes. Christ’s wounds, for example, were specifically invoked during times of the Black Death as intercession to God. Editor: So, a potent object. The image, cheaply and easily reproduced, served to soothe societal anxiety through a focus on sacrifice. Were the artists recognized as skilled craftsmen, or merely anonymous facilitators of a message? I'm curious how the production mirrors the hierarchical society from which it came. Curator: The fact that the artist is anonymous makes it even more significant because it points to collective consciousness during the medieval period. It becomes less about individual genius, and more about the symbolic power of the image itself and the faith of the population. Editor: I see your point. And though my interest stems from the materiality of its production and consumption, the image succeeds as a tangible item for solace in troubled times. It’s a remarkable synthesis of making and meaning. Curator: Yes, it speaks volumes about the cultural currents of its time. A piece with a humble presentation, perhaps, but monumental implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.