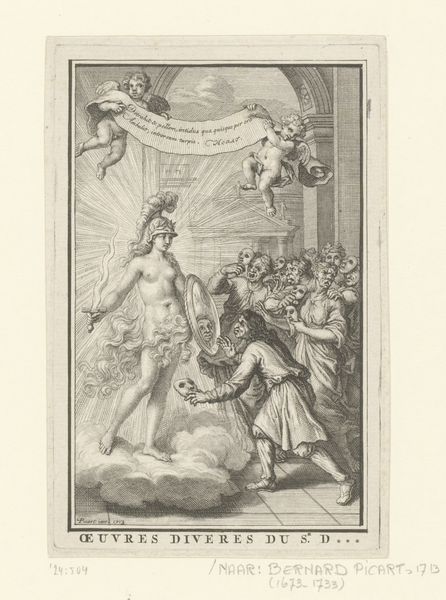

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

caricature

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 183 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving by Abraham Bosse, active roughly between 1612 and 1676, titled "Vrouw door drie mannen en twee vrouwen geboeid." The work can be found here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your first impressions? Editor: Oh, dear, the title is quite on the nose! I feel trapped just looking at it – a very ornate, slightly claustrophobic composition, wouldn't you agree? All these characters crowding around. It almost feels like a fever dream, all very proper yet chaotic! Curator: Indeed. As a printmaker, Bosse was deeply concerned with the means of production and the consumption of images. Prints made art accessible, allowing wider audiences to engage with socio-political commentary. Considering the explicit title, we can infer Bosse probably intended this image as a form of caricature or satire. Editor: Ah, so a critical jab. It has the vibe of courtly intrigue gone completely haywire. The detail is incredible; look at the costumes and facial expressions! The woman’s sheer desperation...it’s like theater. Is this referencing a specific event or social ill of the time? Curator: Possibly both. Prints of this era served as a form of social commentary, engaging with prevalent themes like power, gender, and social mobility. The presence of military figures juxtaposed against traditionally "feminine" ones indicates power dynamics, perhaps the subjugation of the "feminine" by the "masculine," even as all figures are bound by societal expectations and theatrical affectation. Editor: Theatrics, yes! I agree entirely! Everything about it, the costuming, staging, and the exaggerated emotions screams high drama, only made more tragic and unsettling by the precision and detail only an engraving could bring. But looking closer, the "frame" at the bottom filled with luscious looking fruit really undermines any sense of high seriousness and really emphasises the point about the means of consumption. Curator: Indeed. These sorts of material details—who had access to, purchased, and discussed these images—tell us much about their role in constructing social meanings at the time. Bosse was clearly commenting on specific dynamics present in his social circle. Editor: Well, whatever its meaning, the work really seizes your attention. There is a brutal beauty about this work, and I would wager, for all the centuries between then and now, it can still hit a raw nerve. Curator: Precisely. Bosse’s sharp observations on power and representation remain startlingly relevant. A work whose lasting strength resides both in the material and in the message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.