painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

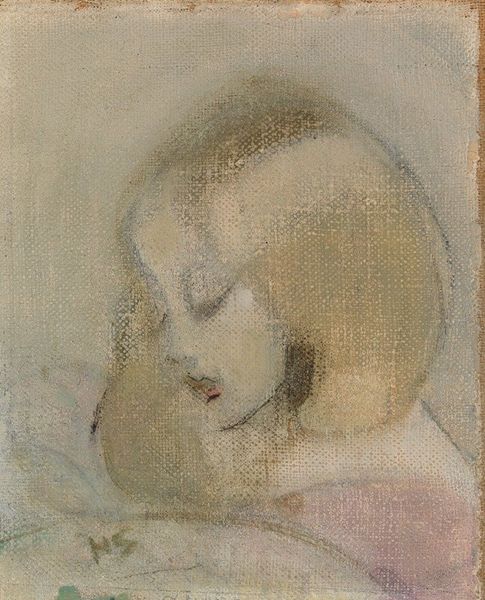

Editor: So, this is "In Repose," an oil painting by James Jebusa Shannon. It's... soft. Hazy, almost dreamlike. It feels really intimate. What can you tell me about this work? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider this piece through a materialist lens. The visible brushstrokes, the way Shannon allows the paint itself to almost define the form... How does this immediacy affect our understanding of portraiture, historically often associated with wealthy patrons and a very polished aesthetic? Editor: It feels almost unfinished. It’s far from the formal portraits you'd usually expect. The artist clearly puts the gesture of applying oil-paint before the "perfect rendering". Curator: Exactly. And where did Shannon get his materials? What was the system of art production at the time? Was this approach considered radical? It shifts our attention to the artistic process, the labor involved. Notice also the palette – muted tones. How does that play into the larger context of impressionistic painting and its market at the time? Editor: So you’re saying the “unfinished” quality isn’t just an aesthetic choice, but part of a whole system of art production and consumption? Maybe it challenges the older, academic style of painting which required more labor and very smooth finish, which made the painting expensive... Curator: Precisely! Consider how the ease of oil paint and canvas enabled artists to step outside traditional workshop training that promoted perfect finish... it changed art's relationship with both its patron and audience. So it isn't just what is represented but also how it’s made that makes it such a profound expression. Editor: I’d never really thought about a portrait in terms of the cost and availability of its materials before, but it changes the way I look at it. Curator: Right? Understanding art’s means of production reveals so much!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.