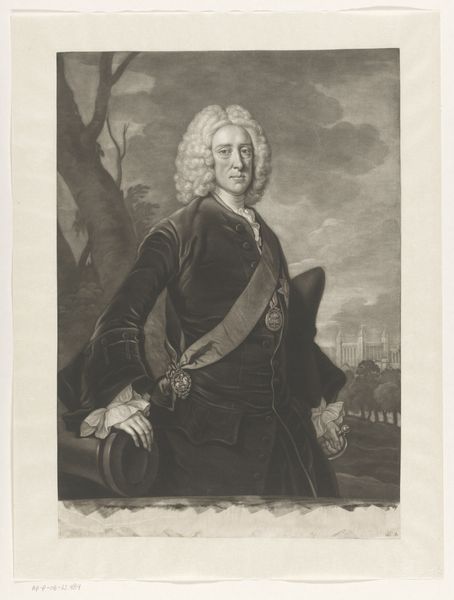

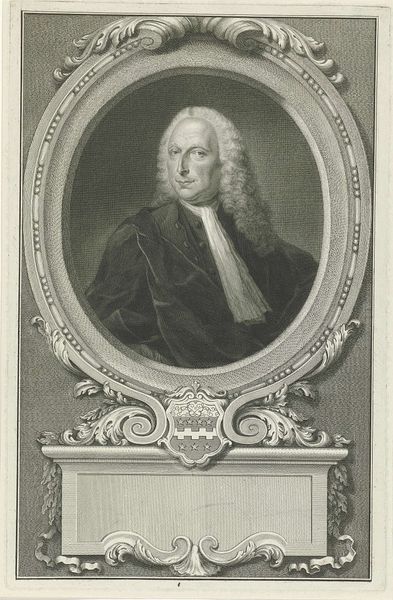

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

historical photography

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 351 mm, width 249 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

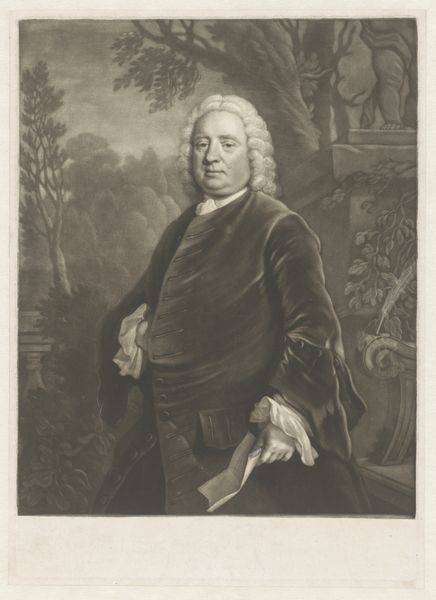

Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the texture in this print. It seems meticulously rendered. The play of light and shadow is striking. Editor: Yes, that's "Portret van Arthur Dobbs," created between 1754 and 1765, now held here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s an engraving on paper, a portrait by James McArdell. Notice the ship in the background? Curator: The ship positions him firmly in the context of colonial expansion and trade, a clear indicator of the resources invested and extracted to enable this portrait’s very production. And it isn't just about resource extraction but about claiming territory. Look at how Arthur Dobbs firmly grasps a map in his left hand! The portrait implicates labor in all of its stages. Editor: Absolutely. Dobbs served as Governor of North Carolina. This portrait signals the consolidation of British power and control in the Americas. Curator: Indeed. We must consider what kinds of paper were being circulated and used. What dyes made up the ink to create these striking tonalities? The print itself is a commodity, reflecting complex trade networks that facilitated its production and distribution. I find myself wondering about the journey of the raw materials and labor that ended up composing this print. Editor: It also highlights the role portraiture played in constructing the identities of colonial administrators. This image was likely intended to project authority and competence, both at home and across the Atlantic. These images reinforced certain ideologies. Curator: And how the consumption of luxury materials - clothes, pigments, and yes, maps! - elevated the social standing of individuals. It’s not just a portrait of a man but an index of broader material and economic forces at play. The material world literally constitutes him, defining his position within this larger scheme. Editor: Thinking about the circulation of this image also raises important questions about the projection of power and authority within the empire. These kinds of images were tools. They helped to cultivate a sense of shared identity among the elite and reinforce social hierarchies. Curator: It all speaks to how art objects participate in material systems that stretch across continents, economies, and social structures, intertwining artistic expression with exploitation. Editor: I'm struck, ultimately, by the ways this image serves as a historical document and a constructed representation—each telling a different but overlapping story about colonialism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.