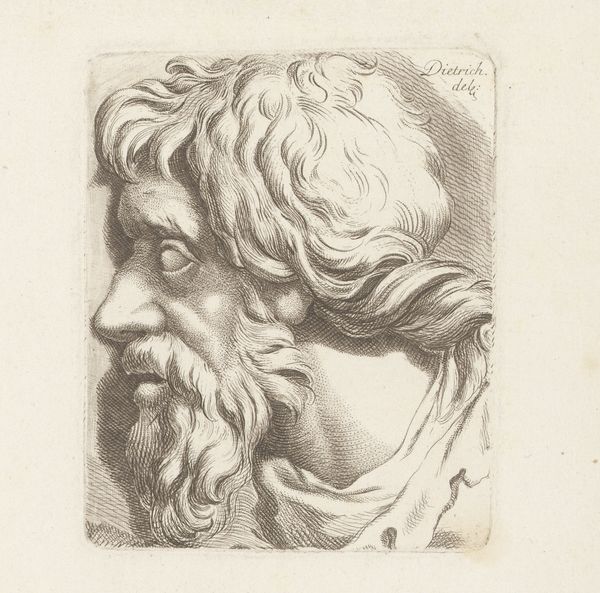

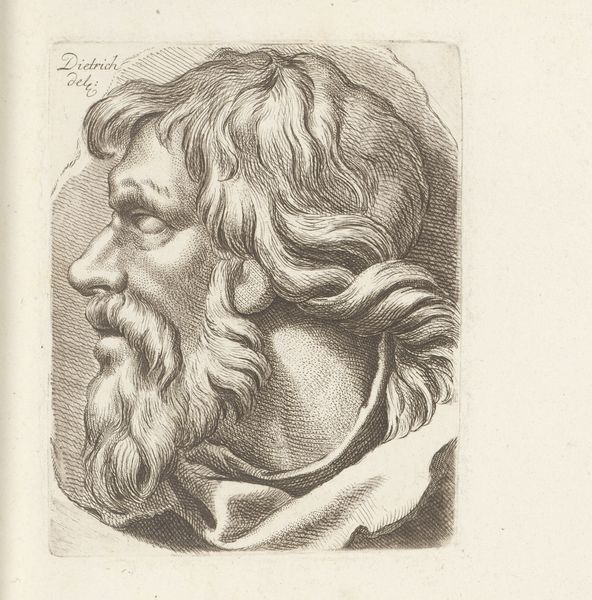

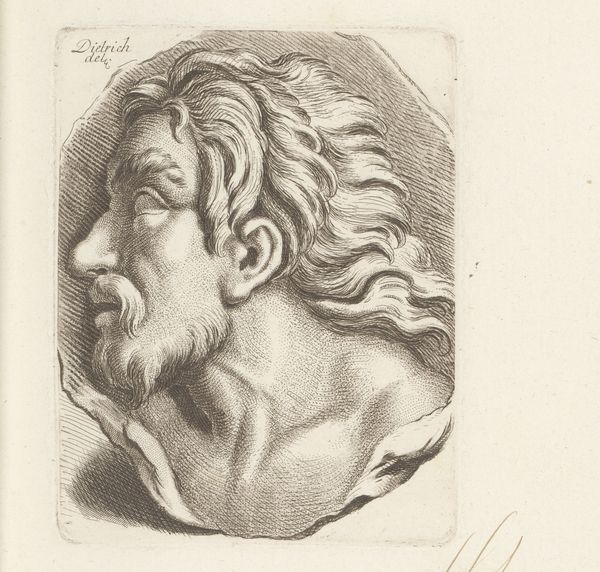

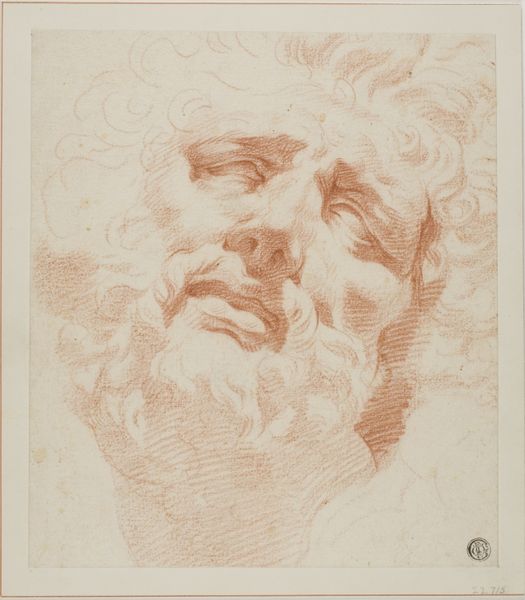

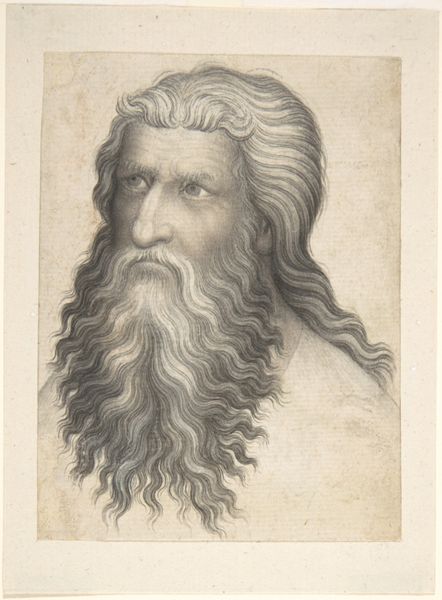

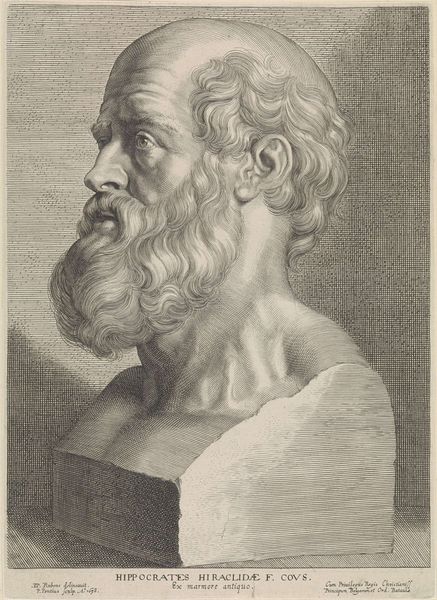

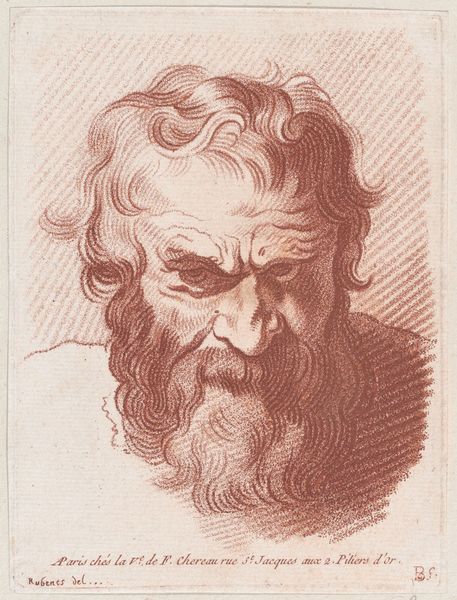

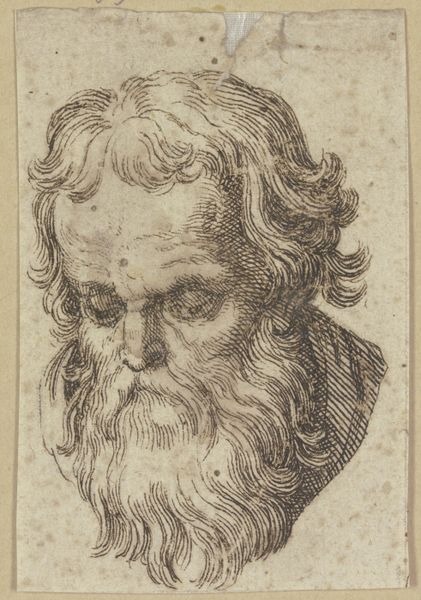

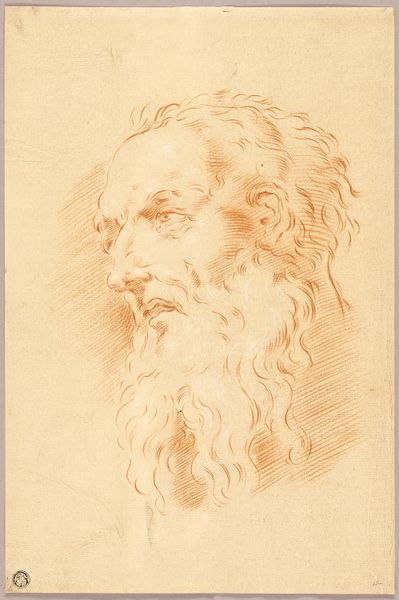

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

classical-realism

#

form

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

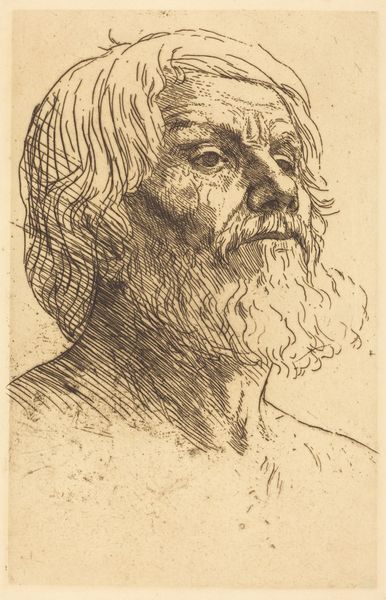

Curator: I am really moved by how time stands still within Carl Friedrich Holtzmann's "Head of an Antique Sculpture," which they believe he made sometime between 1750 and 1811. There is just something about the lines of an etching that seems so permanent. It really makes you consider our relationships with artifacts and time. What do you feel looking at this piece? Editor: There’s a distinct formality here, a stiffness that I immediately read as exclusionary. It's as if the very material—the print itself—and the aesthetic of classical realism conspire to elevate this idealized Western masculinity above all else. It makes me ask questions about the power structures at play in dictating what we consider to be high art, and who is being omitted from its narrative. Curator: I hear you, and that is absolutely something worth paying attention to here. And yet, for me, it almost feels like I am peering into this beautiful conversation across time. Holtzmann took great care in capturing light, shape, and form here. It has that unmistakable Neoclassical precision, which is more romantic to me than elitist. Editor: I agree with you that his rendering is technical and visually arresting; it’s undeniable. However, these formal elements also reflect specific socio-political values. Think of the Enlightenment's obsession with reason and order mirrored in this obsession with classical forms. Curator: Perhaps, it also resonates because the past often feels so intangible to me, just whispers really. In its details I can nearly feel a sense of connection and understand what life might have been like, how ideas were viewed, even what that era valued in men. To see the original sculpture must have been such a thrill for the artist to dedicate an etching to its visage. Editor: Definitely, what is exciting is the dialog the piece brings up today! But let's remember it does so while consciously upholding aesthetic conventions that privilege very particular, exclusionary, histories. As we observe it, we must always keep asking ourselves to investigate who gains from the continuation of such a canon. Curator: Always important to look closer! What remains with me most is Holtzmann’s hand, working to bring the past to his present—and to mine as well. I can think of so many sculptures that are meaningful to me and have stayed in my heart. It feels like I, too, want to dedicate art to them as Holtzmann did. Editor: And by engaging critically with it, perhaps we can forge new, inclusive paths forward and envision a more democratic representation of beauty.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.