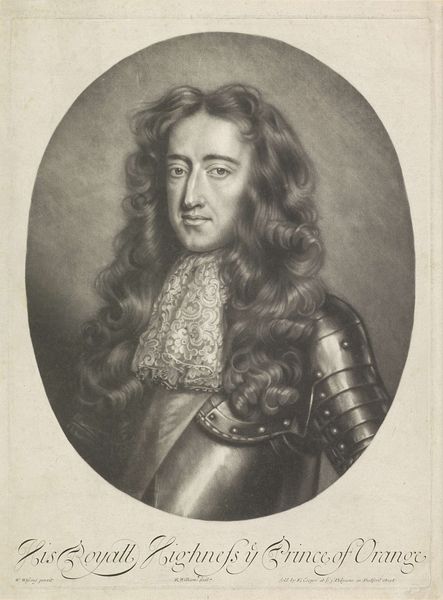

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 196 mm, width 134 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Pieter Schenk’s engraving, a portrait of Willem III, Prince of Orange, dating from between 1688 and 1711. Editor: It's a rather imposing image. The elaborate wig, the crown, the armor... It screams power, doesn’t it? A deliberate construction of authority, right down to the rigid oval frame. Curator: Precisely. Schenk was known for his prints, and this piece demonstrates how these images functioned within the political landscape. Consider Willem’s reign—the historical context is crucial. This engraving would have been disseminated widely, shaping his image, cementing his authority following the Glorious Revolution. Editor: I’m struck by the contradictions. On one hand, we see the formal, almost stiff portrayal befitting a monarch. But there's also something vulnerable in his gaze. What’s the effect of positioning such a monumental figure within such an intricate, detailed, almost fragile medium like an engraving? Curator: The engraving style lends a certain texture, a richness, even to the stark presentation. It emphasizes detail – notice the intricacy of the armor, the fur trim. This highlights wealth, status, and martial strength—all crucial components of his public persona. It’s also Baroque in style. Editor: I see that emphasis on detail. How are we meant to contend with such carefully crafted portraits? Is this representation, or more strategic self-fashioning through a deeply political aesthetic? What does it tell us about the intended audience, the networks through which it traveled? Curator: That’s absolutely key. Prints such as these weren’t passive artworks, they were active participants in political discourse. They affirmed power, promoted loyalty. Their very accessibility ensured a wider reach and impact than paintings reserved for elite circles. Editor: The power of replication... a potent political tool. When I consider this piece in our current context, I am mindful of images still working to shape perceptions and maintain structures of authority and inequity. Curator: Indeed. Analyzing how rulers and institutions used images throughout history helps us become critical viewers of the present, discerning the power dynamics embedded within visual culture. Editor: Ultimately, studying art such as this allows us to unpack the stories behind the image, examining who benefits from particular representations and whose voices might be intentionally or unintentionally excluded.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.